Black scientists from Iowa State

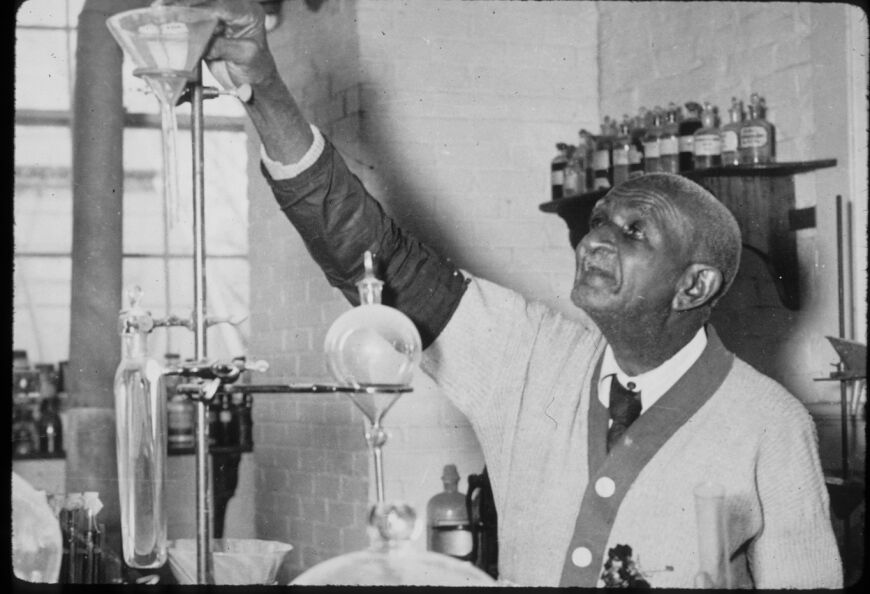

Pictured: George Washington Carver. Black scientists from Iowa State have led and been involved with well-known projects whose research we benefit from to this day.

February 4, 2021

Many important Black scientists have walked Iowa State’s campus, and their legacy continues today.

According to the Pew Research Center, in the United States today Black people make up approximately 9 percent of the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) workforce.

Despite the small percentage, Black scientists throughout history have made many contributions to STEM despite severe racism and limited opportunities, including on Iowa State’s campus.

One of the most well-known Black scientists is George Washington Carver. Carver was the first Black student to graduate from Iowa State, as well as the first Black faculty member. Carver was on campus from 1891 to 1896.

Carver was very active on campus and attained various leadership positions. He was a leader in debate club, captain of the campus military regiment and a trainer for athletic teams.

While his focus was in horticulture, Carver was also fond of the arts, and his poetry was often published in the school newspaper. Two of Carver’s paintings were also displayed at the 1894 Chicago World’s Fair.

According to the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences website, “He earned his bachelor’s degree in 1894 and his professor, Dr. Louis Pammel, encouraged him to stay at Iowa State and pursue a graduate degree.”

At Iowa State, he wrote several professional papers that received national attention. After moving to Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, Carver became well known for his teaching methods.

“His teaching stressed the ‘hands on’ approach, as he encouraged poor farmers to diversify and rotate their crops, grow local food crops to nourish their families and develop pride in their farmsteads,” according to the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences website.

Carver received many awards over his lifetime, including the Roosevelt Medal and the Fellow of the Royal Society in London. He also received an honorary doctorate from Iowa State (College of Agriculture and Life Sciences).

Carver is credited with over 300 uses for peanuts and 150 uses for the sweet potato. Some of his inventions include axle grease, diesel fuel, glue, linoleum, printer’s ink, laundry soap and insecticide.

While Carver said he believed his research was, “simply service that measures success,” according to the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences website, he is well known across the world for his contributions to agriculture.

While Carver’s contributions broke barriers for Iowa State students, they still faced many challenges.

According to Alex Connor in “A History of Diversity: Iowa State over the years,” students of color were allowed to attend Iowa State from the start, but “Black students attending the university, by unofficial policy, were not allowed to room with students who did not share their same skin tone.”

There were very few rooming options for Black students, making it extremely difficult for them to attend.

After Carver attended Iowa State, “another black student wouldn’t graduate from Iowa State until 1904, and it would be another 10 years before the third black student to attend Iowa State would graduate in 1914,” Connor wrote.

In order to combat this, Archie and Nancy Martin built a house that would become home to at least 20 Black students.

Martin Hall was named in 2004 to honor their commitment to Black students.

Samuel P. Massie was one of these students.

Massie was a Black scientist who received a doctorate in chemistry from Iowa State, and is most well known for his work under Henry Gilman during the Manhattan Project.

Massie attended undergrad at Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal College, now known as the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff.

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, Massie decided to continue his academic studies to find a cure for his father’s asthma. He received a master’s degree in chemistry from Fisk University before going on to Iowa State for the doctorate program in organic chemistry.

Due to racial bias, Massie was not allowed to live on campus or work in any of the white labs. He lived in the Martin House during his time on campus and worked in the basement labs.

In 1943, Massie attempted to renew his draft deferment in Arkansas on the basis of continuing his education, but he was denied because he had “too much education for a ni**er,” (Atomic Heritage Foundation).

Gilman quickly recruited him to work on the Manhattan Project in the Ames lab.

Massie said in a 1964 interview, “All of us had to make a decision how we would serve the war efforts. I dropped out of school and went into the chemical warfare service with Dr. Gilman at Ames.”

After the war, Massie received his doctorate from Iowa State in 1946. He went on to teach at Fisk University and became a program director for special projects in science education at the National Science Foundation. Through his work in Washington D.C. with the National Science Foundation and his presidency at North Carolina College, Massie received attention from President Lyndon Johnson.

Johnson then appointed Massie to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1966, where he was the first Black professor.

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, “Massie was named one of the 75 most distinguished chemists of the 20th century. He was one of the three African Americans honored with this distinction.”