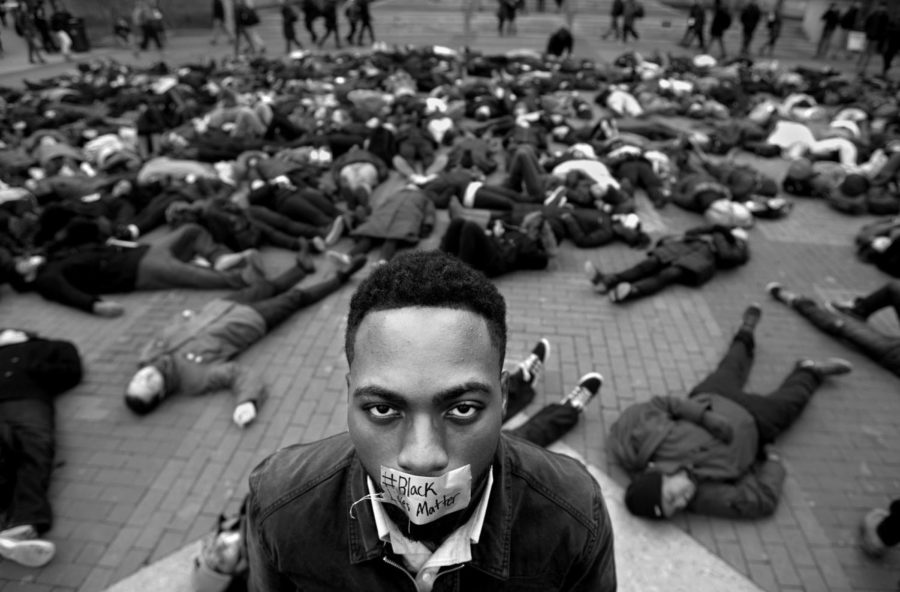

Iowa State Voices: The whitewashing of Black history

February 4, 2021

Would you rather live in a world where everything on the surface looked clean and shiny, but behind the rose-colored glasses there were millions of marginalized people silently struggling, yelling and reaching out for help? Or would you rather live in a world where struggle, social issues and authentic history isn’t pushed aside, but is instead embraced and taught to different communities? While the world wouldn’t be “clean and tidy,” it would ring true.

Unfortunately, according to Novotny Lawrence, an associate professor at Iowa State, the world aligns with the former, and could continue to for generations if people continue to “sanitize” Black history.

“I think that when we have something as critical as Black History Month […] whitewashing can also be considered kind of sanitizing narratives, making them go down a little bit more smoothly and removing things like the pain and oppression that’s associated with certain atrocities in order to make a mass audience feel better,” Lawrence said.

According to Reader’s Digest, whitewashing Black history not only adds a rose-colored tint to the world for white people, but it is eliminating color entirely.

“For decades, whitewashing has taken a diverse, multicultural world and tried to paint it one color. The picture has never been particularly pretty,” the article said.

When it comes to defining whitewashing, Lawrence offered multiple perspectives. While he noted that whitewashing often occurs in Hollywood when white people are chosen to play Black or other ethnic characters, he also states that whitewashing encompasses more than just the films and TV shows we watch.

“It can also be about being very selective in the stories that you tell. An example of whitewashing might be picking a hero that everyone is comfortable with like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who certainly deserves praise and to be uplifted, in favor of perhaps a more radical figure who did just as much like Malcolm X,” Lawrence said.

The idea of white people not choosing to uplift stories that make them uncomfortable falls in line with “white fragility.” Lawrence described white fragility as a reason for the whitewashing Black history. As an example, Lawrence discussed the story of Black activist Fannie Lou Hamer.

“We don’t talk about people like Fannie Lou Hamer […] who was beaten very badly in a Southern jail for being an activist. That hurts to hear that,” Lawrence said. “We sanitize the histories and we pick and choose these things that are going to uplift and make people feel well.”

Lawrence noted that the only way to become more understanding, informed and embracing of our richly diverse nation is to push ourselves to be uncomfortable.

When speaking on his experiences with whitewashing of Black history, Lawrence said he believes he has been chosen for certain roles due to the idea of white fragility and uncomfortability.

“I think that because of the way I perhaps look and the way that I carry myself, sometimes I go down a little bit more easily than some other people who belong to my ethnicity,” Lawrence said. “So for that reason, I think that maybe I have been selected for things where someone else [who’s] equally as qualified wasn’t just because of perhaps the way I presented.”

When asked in which facet of life whitewashing is most prevalent, Lawrence focused on the entertainment industry and academics.

According to Lawrence, while most recognize the whitewashing of people of color in the entertainment industry compared to others, there are still many films that white people would never question. He specifically highlighted the issues with the movie “The Help.”

“It’s [‘The Help’] a movie about the experiences of Black maids living in the South in the 1960s starring Emma Stone,” Lawrence said with a chuckle. “Why are we telling the stories of Black people through the eyes of white characters, and how many times have we seen it the other way around?”

Lawrence said whitewashing in the academic setting can be best seen in the narratives that are selected to be taught in our K-12 classrooms throughout the country.

“For example, we don’t talk about slavery, but we talk a lot about George Washington, which we should, but George Washington was also a slave owner,” Lawrence said.

He then continued to stress the fact that the brutal reality and effects of slavery remain to be discussed.

Lawrence noted that people of color to this day feel the effects of slavery, specifically due to the Jim Crow laws that were put in place after the lack of reconstruction following the Civil War.

“As a result [of the lack of reconstruction] in the South, we have that system of Jim Crow segregation, where we had whites-only drinking fountains, whites-only schools. Blacks were not allowed to vote,” Lawrence said. “We see that that has a detrimental effect socially, economically and politically.”

Lawrence said all of these factors are still affecting the amount of wealth for Black community members today compared to their white counterparts.

“There’s an economic disparity here as a result of what didn’t happen after slavery in this country,” Lawrence said.

While the effects of past whitewashing of Black history can still be felt, Lawrence said whitewashing has evolved with history and is still very much present.

“It’s [whitewashing] more sneaky now. In some ways it stays the same in that if we talk about our histories where people aren’t being taught […] in some ways that’s the same,” Lawrence said.

Lawrence warned that Hollywood is still producing whitewashed films, such as “Ghost in the Shell” and “Green Book,” while streaming services are now reliant on subscribers watching shows that 75 percent of which include white leads.

“You have to ask yourselves, ‘Why does this keep happening?’ Well some of it’s economic, some of it’s racism and some of it is economic decisions based on racism,” Lawrence said. “These things become normative, and when things are normative, people don’t challenge them.”

Lawrence stressed the need for white people to push back against these systematic norms and realize how they can do better.

“When you look at Black History Month, let’s see if we can dig deeper and highlight hidden histories,” Lawrence said. “Let’s see if we start hearing about some of these other people, otherwise, we are still sanitizing, and in essence, whitewashing our history.”

Lawrence said continuing to not tell the uncomfortable and hard-hitting stories of the past is like taking a spoonful of sugar, making the hard-to-swallow stories go down easily.

“Sometimes we’ve got to be uncomfortable to learn the truth, but at the same time, doing that with respect and educating folks so we know the full Black experience in this country,” Lawrence said.

Lawrence urges white people in America to take off their rose-colored glasses and see the nation for what it truly is, but most importantly, for what it can be.