Letter to the editor: Problems with political activism among college students

Figure 1-Letter

November 28, 2018

In a time where seemingly everyone has a political opinion they aren’t afraid to share, political involvement seems unavoidable. You probably have a friend or relative (or maybe it’s even you) who posts on social media that you, as a U.S. citizen, have a responsibility to vote and that there is no excuse to not be involved in politics. However, it seems few people are willing to ask the question: Is it always good to vote? To answer this, you need to decide whether it is morally acceptable for you to help decide issues that will have material consequences, good or bad, on the lives of many Americans.

According to the Kantian ethical framework, you should not perform any action that would yield negative consequences if everyone were to do it. If everyone were to vote without fundamental knowledge of the pertinent issues, our government would fall apart. So, assuming you should have a fundamental understanding of any issue you vote on, let’s delve into the problem of young people who loudly (and usually with good intentions) advocate for causes they do not fully understand and influence their peers to adopt the same positions and vote accordingly.

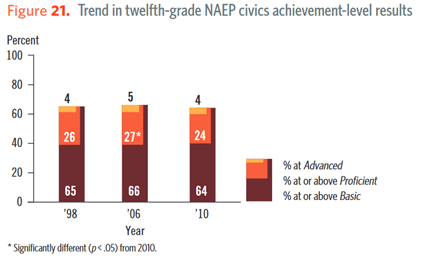

If you are a college student, odds are you do not understand the fragility of the economy, the complexities of international relations, the intricacies of the federal budget, or the vital importance of the philosophy on which our country was founded. While viral YouTube videos of college students offering confused or laughably wrong responses to political questions are one illustration of this, a more concerning and concrete example is the percent of U.S. 12th graders failing to score at a level of “proficient” or better on the Civics and U.S. History sections of the NAEP exam:

Far too often, the opinions college students do hold are engrained in them by the family or culture in which they were raised, narratives pushed on them by media outlets, opinion-trends of their peers or public figures, personal biases, or some mixture of these factors. It is rare to see a young political activist humbly change his or her opinion on a hot topic after being presented with hard statistical evidence that disproved his or her position. More likely, they will react defensively, distrusting the data while seeking out a refutation of it. This is more of an attempt at preserving one’s own worldview and justifying one’s opinions than a pursuit of the truth and the betterment of society.

College students are at a stage of life in which they are still discovering themselves. If you think back to who you were and what you believed four years ago, I’m sure you will find that person is far different from who you are now. In the next four years, your opinions will change, your ambitions refine and your sense of self develop. If you, in this moment, have such a limited understanding of your own self and the fundamental philosophy and morals that drive you, how can you possibly understand what you believe about the intricate structure of our political and economic system well enough to advocate for political causes?

The biggest issue is that college students, generally speaking, have not yet worked full time/year-round jobs to earn a salary on which they pay income taxes. They have not started businesses, hired employees, and navigated pertinent regulations. Most are still on their parents’ health care plans. Most are barely old enough to remember the economic recession of 2008, and have enjoyed one of the most prolonged periods of economic prosperity in U.S. history. How can they understand the struggles of economic downturns? This issue does not have a simple solution and was unforeseen by our forefathers. The voting age of 18 was determined in a time when the majority of Americans aged 18-24 were producers in the economy – working alongside adults on farms or in factories.

So, what should young people do to better our country? Value truth as the highest ideal to strive for. This is much harder than it sounds and could have entire books written about it. Be radically open-minded about every issue with which you interact, and do not adopt opinions simply because they have been deemed popular by the mainstream. Embrace foreign or unpleasant ideas and, if they are clearly morally repugnant, refute them rationally rather than silencing them. Do not shrink the Overton window to exclude opinions you deem unpalatable. When forming your opinions, be sure you can describe the issue in detail and explain the best argument against your position to the satisfaction of a knowledgeable person who holds that position. Until you can accomplish this, your opinion will not be refined enough to justify advertising your view. Attempting to influence others to adopt an opinion that you yourself cannot sufficiently defend is deliberately misleading, morally reprehensible and corrupts our democratic system. Expose yourself to new ideas that run contrary to your existing beliefs. Seek the truth and be radically open-minded in doing so, and you will find yourself coming to understand yourself and the world much more comprehensively. It is not easy, and takes a concerted effort to recognize when you are deceiving yourself for the sake of convenience or preservation of your worldview. But truth is the only path to making the world a better place.

If you involve yourself in politics, do so humbly and cautiously. Seek to learn – not to advocate for an ideology. It is okay to not vote on issues or races you are not well informed enough about to hold a valid opinion. It is admirable to not vote simply based on the “R” or “D” next to a candidate’s name. It is noble to change your opinion. I left half my ballot blank this year because I did not know enough about the pertinent local issues to make an educated decision. I would encourage more young people to do the same.