Banned books raise issues of censorship

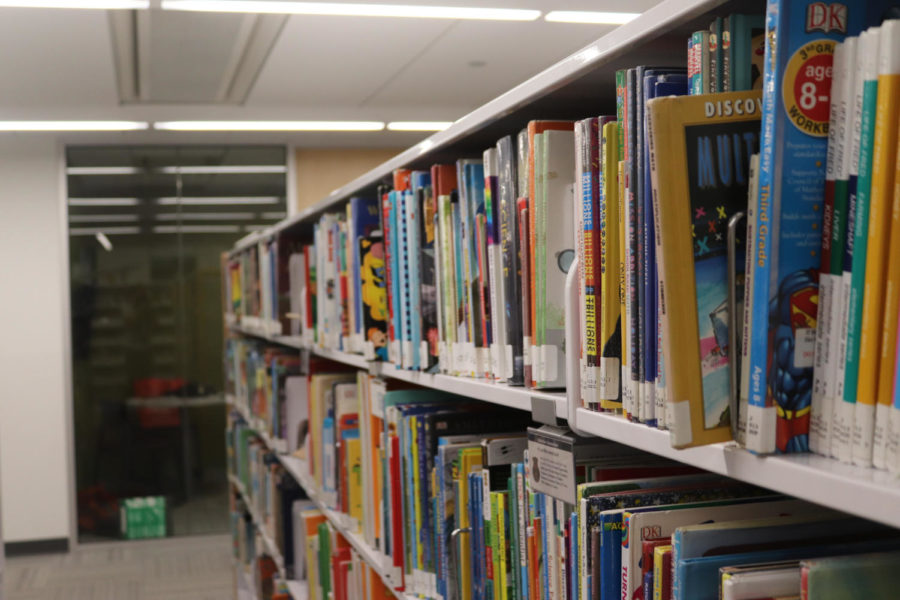

Banned books are contested books that have been removed from school curriculums or public libraries due to content.

During the third week of September, individuals all over the globe celebrated the freedom to read during Banned Books Week.

Banned books are those that were removed from school curriculums or public libraries because some individuals or groups are opposed to its content, according to the American Library Association.

Studies indicate 33% of banned books contain LGBTQIA+ themes, 22% touch on racism and 41% have main or secondary characters of color, according to a report by PEN America.

Dan Coffey, a humanities librarian at Iowa State, said these statistics “proportionally represent the degree to which fear and misunderstanding have permeated our society.”

Banning books bans the ideas found in those books, preventing children from gaining a complete education, Coffey said.

“One of the critiques of the U.S. public education system, and there are a lot of resources that mention this, is that it promotes conservative thinking and behaviors,” said Lorrie Pellack, head of the Research Services Department. “It teaches students to conform to societal norms.”

Of all of the bans listed on PEN America’s index, 41% are linked with directives from elected lawmakers or state officials, and only 14% of book challenges come from parents, based on a study conducted by the American Library Association.

“They [social conservatives] believe that if students are exposed to non-traditional concepts, they will be more likely to become non-conformist or believe in radical ideas,” Pellack said.

Many of the most challenging books are those that used to be required reading in high school literature classes such as “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood and “1984” and “Animal Farm” by George Orwell, Pellack said.

“The Handmaid’s Tale” is often targeted due to its sexual and anti-religious content. Margaret Atwood, the book’s author, created a fireproof copy of her novel as a symbol against censorship to highlight the voices of those who have been silenced, according to the Smithsonian Magazine.

In Ames, many individuals who work for libraries and independent bookstores oppose the banning of books and the silencing of voices.

To combat censorship and the banning of books, Coffey encourages readers to speak up at school board meetings, show support for public libraries at town hall meetings, and frequent their local independent bookstores that advocate for challenged and banned books.

“The urge to ban books isn’t going to go away, but by talking about it and about the issues that book challengers would like to keep students from learning about and discussing with our children, we can limit their effectiveness,” Coffey said.

Pellack said many librarians, including herself, are active participants in “contributing to conversations and encouraging change and growth” to bring light to challenged authors and topics. This goes beyond having a couple of copies of banned books within the library. Many often take action on campus and in their personal lives.

Susan Gent, who works part-time with the Ames Public Library and Parks Library, brings speakers and workshops into both spaces. Pellack shares that the Tracing Race project is another way librarians at Iowa State provide students with more inclusive narratives.

“Librarians protect the right to free access to information…and believe in opening and sharing knowledge with everyone, regardless of who they are or why they want the information,” Pellack said. “It’s no coincidence that one of the most heavily used ‘free speech zones’ on campus is just outside the Parks Library.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of the Iowa State Daily. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, send our student journalists to conferences and off-set their cost of living so they can continue to do best-in-the-nation work at the Iowa State Daily.