Misconceptions regarding student ratings of teaching

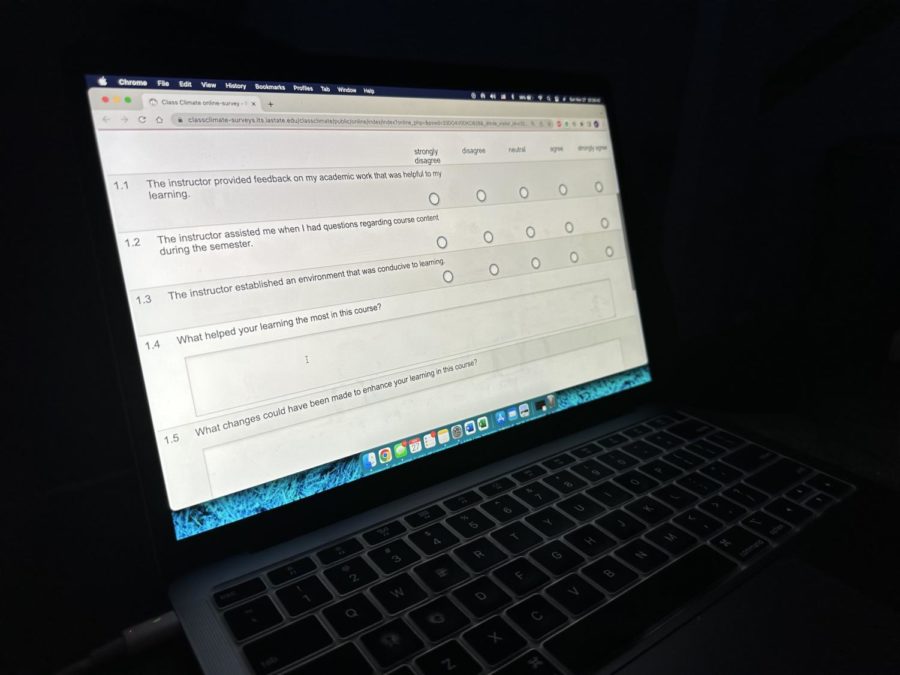

Student ratings of teaching are sent out during the last two to three weeks of a semester, right before finals week. In these evaluations, Iowa State students have the opportunity to give anonymous feedback to their instructors regarding their classes.

November 27, 2022

As the semester winds down, Iowa State students can expect to receive the annual student ratings of teaching surveys.

Student ratings of teaching are sent out during the last two to three weeks of a semester, right before finals week. In these evaluations, Iowa State students have the opportunity to give anonymous feedback to their instructors regarding their classes.

Some students are under the impression that these ratings do not have the impact they may want them to.

“I feel like they currently don’t do anything or create any change that I can see, at least,” said Abigail Fritschel, a junior in aerospace engineering. “It’s frustrating because I hear people have the same complaints I did the next semester, so I know nothing was changed.”

While some students may feel like their voices are not being heard, some professors are under the impression the surveys may hold too much weight.

“I wish they were used differently in the sort of professional evaluation of faculty by our peers or by administrators; they’re weighted pretty heavily, and they’re probably weighted more heavily than they should be,” said political science professor David Peterson.

The student ratings of teaching responses are used in several different ways. When a professor moves from an assistant to an associate or associate to full, the student ratings are asked for in either the nomination process for an award or an overall faculty evaluation.

While many students give constructive feedback, bias is sometimes evident in student responses.

Associate provost for faculty Dawn Bratsch-Prince said it’s an impossible task to eliminate bias from the student ratings of teaching.

“We have bias in so many facets of life,” Bratsch-Prince said. “I don’t think you can eliminate bias, but you can certainly be aware of it, which we are, and then counteract it by not relying solely on one data point on the student weightings of teaching.”

The bias that exists in student ratings of teaching is frequently against women, underrepresented faculty, the older aged and faculty with accents.

“I can’t speak to any specific one of those that appears in student evaluations here, but I think there’s plenty of research that shows that those types of bias occurs, and those are the categories that are typically mentioned,” Bratsch-Prince said.

Along with student ratings of teaching responses, the faculty handbook outlines several other metrics professors should include in the promotion and tenure materials. Some of these metrics include teaching philosophy statements, peer observations and examples of individual areas they have improved or sought help in throughout their teaching, Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching (CELT) Director Sara Marcketti said.

“It’s just one piece of documenting their teaching,” said Gretchen Peterson. “There are several other things that they can do to document that that will supplement the course ratings inside their promotion and tenure materials.”

Gretchen is a part of the CELT learning technologies teams.

The ratings can also serve as early detection for department chairs that an instructor may be struggling with their teaching and needs assistance from a mentor or through CELT or other professional development.

Part of the appeal of the student ratings of teaching is it allows department heads to see common trends and perspectives over multiple years in different semester sections.

It’s not a good idea to base massive course changes on one semester or one section,” Gretchen said. “Sometimes it will take a couple of years, depending on how often classes are offered, before changes are made, and that’s the tough part.”

Marcketti encourages professors to take advantage of midterm evaluations to better their teaching methods and curriculum before the end of the semester.

“If I could ask faculty to do one thing, it would be to insert a feedback mechanism when they were teaching such that they didn’t wait till the end of the semester to get feedback,” Marcketti said. “It’s often small tweaks that are what students need.”

The Plus/Delta feedback tool is an online survey that can be sent out to students around the midterm mark of the semester to get feedback on what can be improved before the end of the course.

Some students want to see an opportunity to give feedback before the end of the course.

“I think if they were in the middle of the semester, it would give (professors) time to read them and slowly start to work on things or change the way that they do things,” said Elizabeth Semple, a senior in psychology.

Gretchen also encourages professors to work on promoting constructive student criticism from their end.

On CELT’s website, there is a page that provides professors with ideas and strategies for better student course ratings before and after the surveys are sent out to students.

Marcketti also mentioned the importance of educating students on why course evaluations are important.

“Instructors telling the students why they matter, and even highlighting things that they change because of student feedback is huge,” Marcketti said.

Gretchen understands that some students may feel like their voice is not being heard through these surveys. She encourages students to use more constructive feedback in their responses. CELT has a pdf document that can be found on their website to assist students in framing their responses in a way that promotes productive change.

“I think until we have a common definition or a common understanding of what good teaching is and how we evaluate it, there’s going to be room for improvement in the evaluation matrix,” Marcketti said.