Guatemala is a fascinating country. Tucked away in lush green mountains and fiery volcanoes lies a rich culture and history. Recently, Guatemala elected their next president, Bernardo Arévalo—a supposed anti-corruption and anti-crime maverick. He is the son of Juan José Arévalo, the first democratically elected president in Guatemala’s history. In 1954, according to Guardian, Arévalo Sr. was deposed by the U.S.-sponsored coup and forced to live in exile in Uruguay.

Before arriving in Guatemala in June, I had few ideas of what to expect. Rarely was anything taught about Guatemala, especially not the detailed past of U.S. interventionism that can be linked to many of the nation’s current woes.

During my brief stint, many politicians were beginning to launch their campaigns. Guatemala City was littered with political advertisements, making America’s trite election system look professional.

Any patch of grass or wall was uncovered quickly and became the battleground for artistic propaganda. At least, this is how my taxi driver explained it to me on the ride to my hotel from the airport.

He described the discontent with politics that many Guatemalans have, claiming that none of it matters. The driver was a self-proclaimed political nihilist.

He had justifiable reasons to feel this way. It is a common thread in Guatemala to be intertwined with the forces of political power and corruption, not to mention cartel and gang violence. The driver explained how his niece had been kidnapped by drug traffickers and moved across the Mexican-Guatemalan border. Eventually, she was released because she had a few hundred American dollars and a small amount of drugs.

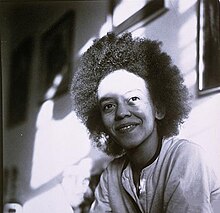

This is the reality for many Guatemalans. The cover photo for this article is one I took not far from the Palacio Nacional (National Palace) in Guatemala City. The people in the image were either missing or had been killed. Most of the ones who were killed were victims of the Genocidio en Rabinal (Rabinal Genocide) in which the Guatemalan government forcefully relocated many Mayan villagers for economic development reasons. According to Wikipedia, those who refused to leave were “kidnapped, raped and massacred by paramilitary and military officials.”

Seeing something like this in person is humbling and heart-wrenching all at the same time. It made me aspire to be on the positive side of history, regardless of the cost or consequence. When a genocide like this occurs, it leaves no room for hope. All faith and commitments cease to exist.

However, a new movement has emerged, prioritizing democratic ideals over the callousness of totalitarianism, fairness over corruption and people over power.

It wasn’t long ago that attacks on progress were made. For example, while I was in Guatemala, famous journalist José Rubén Zamora was sentenced to six years in prison on money laundering charges that are “widely condemned as politically motivated.”

Such a rapid shift in Guatemalan politics is promising but must continue. It can easily be drawn off track again by higher interests and power. We have an international effort that we are responsible for maintaining.

As a nation, we have contributed to the downfall of Guatemala, and now we must cheer them on—for a brighter future.