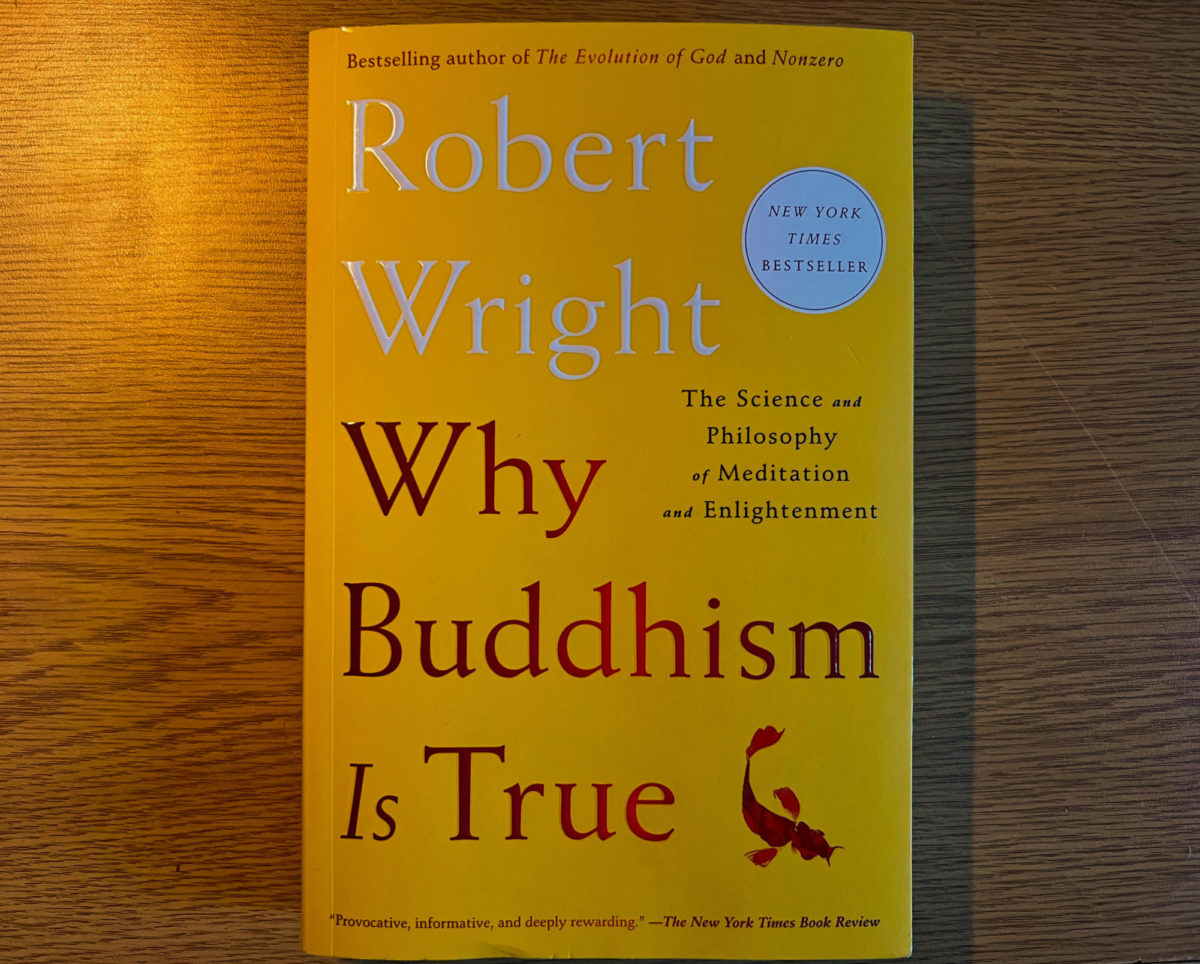

Buddhism has entered the Western lexicon rapidly within the past decade and appears to have great practical value. In his book “Why Buddhism is True”, author and Buddhist practitioner Robert Wright walks readers through Buddhist meditation practice and how such a practice can improve many people’s outlook on life.

What I enjoyed most about the book was its focus on practical application. Wright states from the outset that he doesn’t aim to justify many of the larger religious claims that Buddhism purports. However, he doesn’t fully deny the ancient practices and ideas that could be potentially useful. Wright aims to be fair and empirically correct while maintaining that mindfulness is an individual experience and cannot be done in a “right'” or “wrong” way.

Wright claims to be of the Theravada School of Buddhism and part of an even smaller tradition within the Theravada school called Vipassana. It is within these schools that Buddhists believe in the ideas of “not-self” and “emptiness,” which Wright states in the book makes “the world inside of you nor the world outside of you anything like it seems.”

One may ask, as I did, how ideas such as this can be supported empirically. How would a “normal” person who has no prior experience with Buddhism be able to implement “not-self” and “emptiness” into their everyday lives?

Wright says, “Both our natural view of the world ‘out there’ and our natural view of the world ‘in here’—the world inside our heads—are deeply misleading. What’s more, failing to see these two worlds clearly does lead, as Buddhism holds, to a lot of suffering. And meditation can help us see them more clearly.”

I like this quote because it gives the rest of the book a framework to build off of. This book is about meditation, and Wright does an impressive job summarizing these complex concepts and drawing a clear connection between these concepts and our personal lives. “Not-self” and “emptiness” aid us in seeing the world with clarity. The book’s overall argument lies in identifying mental phenomena and showing how they can mislead us. Feelings, for example, often reinforce illusions about things we encounter in life and garner more stress than they deserve.

Wright holds that “natural selection didn’t design your mind to see the world clearly; it designed your mind to have perceptions and beliefs that would help take care of your genes.”

Thus, the driving force of feelings is based on the formation of a primitive mind. And this primitive mind often gets lost in the highly unnatural processes of cultural transformation—think of humans working together in hunter-gatherer groups and how simple these interactions were to what we deal with now.

The advent of complex technologies and social platforms detach us from ourselves even though we cannot truly be detached from our own minds. Stemming from these processes is a muddled view of life, where common mental health issues such as depression and anxiety lie. They are produced by needing a reconciled view of the past, a clear path forward for the future, and, most importantly, an ability to live in the present.

Being able to slow down and be more mindful of the present moment will allow us to tap into a more clear and peaceful life.

In my estimation, this book manages to fuse a modern self-help attitude with a comprehensive analysis of Buddhist philosophy while maintaining an adherence to the literature presented by evolutionary psychology and neuroscience. Wright has done a fantastic job of making Buddhism accessible and useful for every reader.

Overall rating: 8/10