Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy (NRS) was released in 2013 in response to a federal call for plans to reduce nutrient pollution in the Mississippi River. The federal government wanted to reduce the total amount of nutrient pollution in the Mississippi by 45% by 2035 as a “dead-zone” was forming in the Gulf of Mexico.

This is an area of water where excess nutrients feed microorganisms who consume most of the available oxygen in the water, disallowing macro life such as fish to survive. Iowa worked with Iowa State University, Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship and others to form this state specific strategy to reduce Iowa’s nutrient pollution in waterways.

Iowa has its own motivations to reduce nutrient pollution: it can make Iowans sick and cause algal blooms in our state waters. The NRS itself is essentially a document calling for more regulation for point-source pollution (wastewater and industrial) and voluntary measures for non-point source pollution (agriculture).

Point-source pollution is easily tracked in a system and enters the environment at a specific point, such as industrial waste leaving a factory. Non-point-source pollution is not so easily tracked, such as what ground water in a stream passes through. There is a lot more to say about the formation of the NRS, but this isn’t a textbook article on the NRS. This is an opinion article on the NRS’s failure over 10 years later, specifically for non-point source pollution. Spoiler: the regulatory approach toward point-source pollution seemed to work.

How would I measure the success of the NRS? I would probably test Iowa’s water to determine the amount of nutrients in the water. There are difficulties with this, as the total amount of nutrient pollution will be higher in rainy years and lower in drier years, so it would take years to determine if the NRS was working. Luckily, I am writing this years after its introduction.

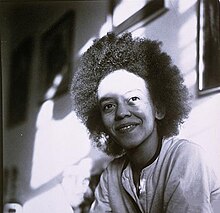

Chris Jones, a former researcher in charge of the state-wide water quality monitoring system, has repeatedly said Iowa’s water quality has worsened and the NRS is not working. Allegedly, state lawmakers were upset with what Jones was writing and threatened to slash his funding.

In response, Jones retired and lawmakers defunded the state-wide water quality monitoring three weeks later. The Iowa Nutrient Research Center lowered its own funding to help keep the water quality monitoring active. The long-term financial sustainability for this monitoring is still in question. This system is the only of its kind in the state and the only way to currently measure Iowa-wide water quality consistently.

Iowa lawmakers and the state secretary of agriculture would tell you this isn’t of great importance. They disagree testing water is the best way to determine if the NRS is working. They prefer looking at the “input” side instead of the “output” side. They say farmers have greatly increased conservation use over the past 10 years. Cover crops, wetlands, buffers and new practices like saturated buffers have increased in acres across Iowa.

Iowa State reports the area covered by edge-of-field practices like wetlands and buffers has gone from about 80,000 acres in 2012 to about 150,000 acres in 2021. These practices don’t need to only increase. They need to completely treat or cover Iowa’s agricultural fields to meet the water quality improvement “scenarios” listed in the NRS document.

See, the NRS does not include any measures by which to determine success or failure for non-point source pollution. It does not include any benchmarks, goals, or a timeline by which the 45% reduction in tons of nutrient pollution coming from the state should occur. It is an incredibly weak strategy that says it’s science-backed (more on that later; it’s not).

The only semblance of a standard or goal are eight scenarios that could potentially exist that are expected to achieve nutrient reductions. The Iowa Environmental Council looked at scenario one of the NRS and the number of best management practices for agriculture in Iowa in 2018. They determined at the current rate of adoption that it would take over 20,000 years to reach the number of best management practices laid out in scenario one.

Proponents of the NRS say adoption will be exponential and not linear. However, there are major problems with the input-only measure of success and the belief that practices will become greatly exponential in adoption. One problem is the “negative” inputs, like fertilizer use and the number of animal confinements, has risen along with the “positive” inputs such as best management practice adoptions.

The other problem is that most of these conservation practices are done through “cost-share.” Taxpayer money is given to farmers to offset the cost of adopting conservation practices partially or completely. An exponential increase in practices would require farmers to pay for practices by themselves or for subsidies to increase exponentially. I genuinely cannot say which is more unlikely.

There are other methods one could look at if the NRS is working, such as the number of impaired waters in Iowa. Impaired means the water body, such as a lake or stream, cannot be fully used as it is intended to be. This could mean the water body isn’t safe to swim in if it was meant to be swam in, or that it can’t be fished if it was intended to be fished. That number has remained roughly half of the waters in Iowa. Impaired waters are not improving.

This first article may seem information intensive, but I have attempted to simplify the content to address my main points. This foundational knowledge is presented so readers may better understand my next articles. In the meantime, if you are curious, Jones has his own blog of opinions.