It was a beautiful afternoon in central Iowa. The temperatures were in the lower 70s. It should have been a nice walk across campus, yet the chatter in mind grew louder. “Congratulations on receiving this prestigious honor” played in my head again and again.

The words emphasized the good news I received earlier that morning. I was appointed to the George Washington Carver Endowed Chair. “This is truly well-deserved recognition of your outstanding contributions,” read the letter.

The congratulatory words revealed in my mind an image of the younger me writing applications to colleges in the United States. It was in the mid-1990s, and back then, I did not have access to a computer for word processing.

When I was writing the college applications, I often heard my mother’s voice in my head: “Your handwriting needs work.” I felt humbled to admit to myself that I had been working to improve my writing since I was a child.

When I was in elementary school, mom, who was a teacher, spent countless hours instructing me in how to shape vowels in my miniature chalkboard. In those childhood times in rural Tanzania, first-graders did not use notebooks and pencils for writing. Most parents couldn’t afford school supplies. Even though my mom could afford the items, we were taught to be respectful of others, which meant using the same resources as my peers.

What a journey to becoming a college professor deemed worthy of an award named after a legend. Carver was Iowa State’s first Black student and faculty member who went on to revolutionize agriculture in the South. I was elated about the honor. Yet the gravity of the award named after the Black American made me feel nervous.

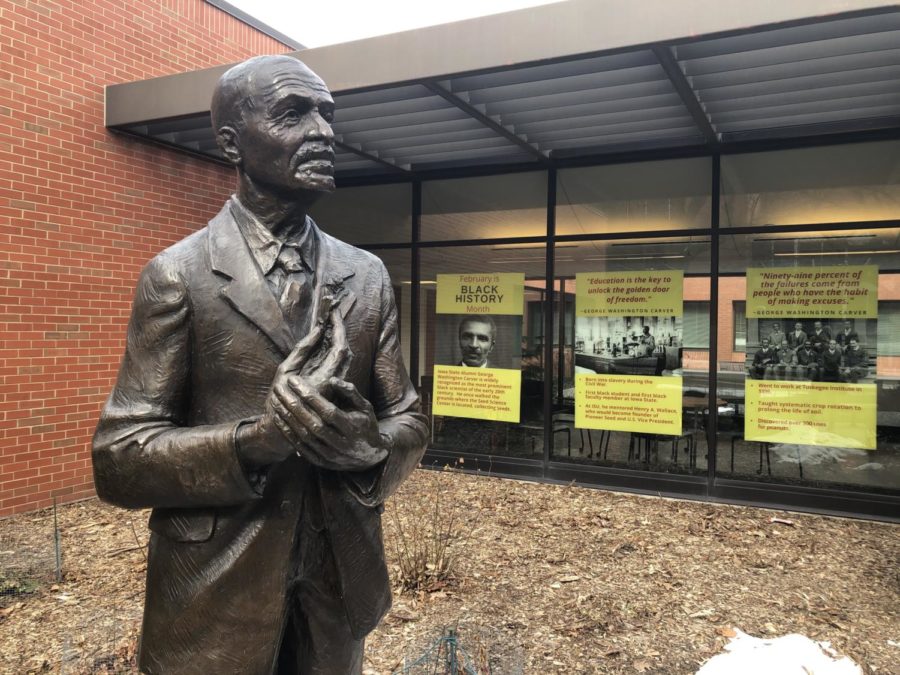

My walk that afternoon was meant to help me reflect and modulate my nervousness. The walk led me to a spot on campus where a bronze statue of Carver stands. The statue presents the adult Carver, dressed in a suit, hands clasped together, his left hand over his right, his right index finger and thumb holding a peanut. One had to know the story of Carver to realize that the object between his fingers was a peanut.

But Carver was about more than peanuts. He was also a spiritual man. I thought of a quote by him saying: “I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting station, through which God speaks to us every hour, if we will only tune in.”

I wanted to tune in, so I stood there for several minutes looking at the statue. “Thank you. It is hard to fathom what you went through in life,” I said to Carver in silence.

I wished I could communicate with Carver through his statue to let him know that I knew that he loved art and music. Yet, the arts would not have allowed him to earn a living in the 1890s. I wondered how it must have felt to give up the arts for agriculture. How did it feel to pursue a vocation that created so much pain for enslaved Africans?

Nothing bad that happened to me will ever come close to what Carver and enslaved Africans experienced. Sure, my life changed after a violent mob burned down my childhood house. Sure, losing our farm took away my family’s livelihood, forced me to be out of school and caused me to do menial street jobs. Yet the jobs were frequently temporary, so I found myself among a group of unemployed youth, constantly wishing to be back in school.

Carver was born a slave, his name was from his White master. He experienced racism to the point of calling himself an “orphan child of a despised race.” Despite the injustices, Carver grew up to love Black people as well as White people.

Yes, my childhood experiences may have prepared me to be more compassionate with others, but I will never know how Carver felt to witness a Black man being lynched.

I had more to say to Carver. I wondered what he might say to me for deciding to write newspaper columns about the intersections of spirituality, antiracism and social justice. I wondered what he might say now that we are witnessing programs meant to increase diversity in historically white institutions being decimated in certain parts of the United States.

I wondered what he might say today regarding the racism that still clouds Black lives. I wished to hear from Carver, yet the statue remained silent.

The silence did not stop me from seeking Carver’s counsel. I sharpened my focus on the peanut in Carver’s hand. Doing this created a thought that perhaps the peanut gesture was heralding me to focus on what was in my own hand. What was in my hand that afternoon was my phone. I bring my phone with me on my walks to take pictures and notes for my writing. But what should I do? I recalled another quote by Carver: “Start where you are. With what you have.”

What I have is my writing. I have been writing all my life. I have written exams, theses, dissertations, funding proposals, reports, lessons, research articles, job application letters, essays for newspapers and magazines and emails. All this writing converged as I faced Carver’s statue that afternoon. I must continue to write.

More than ever I must write the heroic things and also the sad things that happened to Carver and his forebears. More than ever, I must write about America’s past oppressions. I must write to counter concerted efforts to bar the teaching of African American history.

Carver believed that “It is simply service that measures success.” To honor Carver, I must write in service to others.

_________________________________________________

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Iowa Capital Dispatch