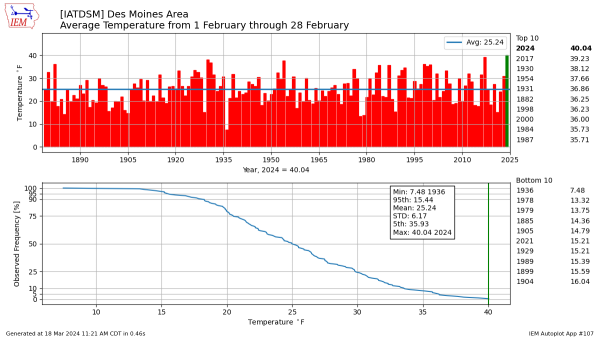

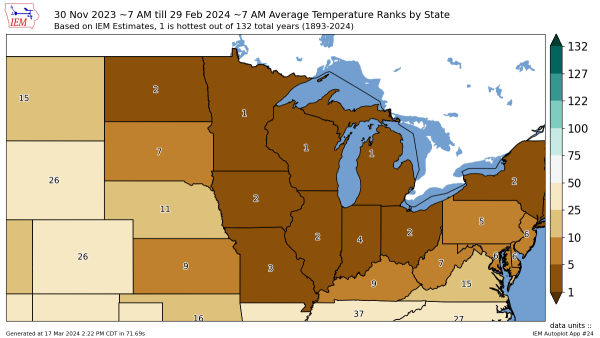

Iowa temperatures in February were a record-breaking 13.5 degrees F warmer on average than usual according to the Iowa Climatology Bureau Chief and State Climatologist Justin Glisan.

“And if you look at our history […] our winters in particular have been getting warmer. That’s part of the overall global trend of what I would say is human-caused global warming,” Bill Gutowski, an Iowa State meteorology professor, said.

During the meteorological winter, which is December through February, Iowa experienced record highs and its second warmest meteorological winter which was 7.8 degrees F warmer than average, and only second to that in 1877.

El Niño

Glisan, who works within the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship, said a large but not all-encompassing reason for the warm winter and overall winter can be attributed to the climate phenomenon El Niño.

“Trade winds in the equatorial Pacific start to slow down during El Niños, and that allows warmer sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific,” Glisan said. “With those warmer waters, the atmosphere responds and produces thunderstorms. Where are those thunderstorms set up impacts for the jet streams set up over the United States.”

Glisan, Gutowski and Daryl Herzmann, a systems analyst for the Iowa Environmental Mesonet, spoke about the climatological impact of El Niño, and its opposite, La Niña, which typically causes colder weather.

The increase in thunderstorms and rise in surface water temperatures have caused an increase in national temperatures in the United States.

It’s important to note that El Niño is a factor in the record-breaking winter but not the catalyst. Human-caused climate change and a trend in upward yearly temperatures are also to blame.

“If you look at 1895 when the federal record starts the official record, we’re about 1.3 degrees warmer than we were at the end of the 1800s,” Glisan said. “If you look at the last 30 years, we’ve nearly tripled that temperature rise.”

Agricultural impact

Along with the environmental effects of the El Niño, a lack of snowfall has also led to warmer temperatures.

“In the winter season here, we need to have sources of very cold air visiting us frequently,” Herzmann said. “Typically that happens when we have persistent snowpack but if we don’t have snowpack here, which is more common, because we’re a bit further south, at least Minnesota typically has persistent snowpack.”

Minnesota has also had an unseasonably warm winter with limited snowfall with minimal cold air traveling to Iowa, according to Herzmann.

The amount of snowfall doesn’t just impact temperatures, it also impacts Iowa’s agricultural industry.

Glisan said the lack of snowfall also led to a lack of precipitation contributing to the drought that Iowa has been in since May of 2020. Due to the ground never fully freezing during the recent meteorological winter, precipitation was not hindered from entering the soil but the wind and humidity in February removed that moisture.

“Of course that has implications on that soil moisture that we need for the growing season given our row crops; corn and beans that we plant,” Glisan said. “So a dry February perpetuates that drought, holds it, and we’ve seen some intensification of drought conditions.”

In addition to this, the reduction of winter precipitation removes the possibility of snowmelt flooding but decreases water levels for barge traffic that transports agricultural commodities.

“If the river levels are low, that impacts how fast those barges can get up and down the river which adds cost to farmers,” Glisan said.

Looking Forward

Will the winter high temperatures determine weather conditions for the spring and summer? Glisan says no.

According to Glisan, the El Niño is fading. During the summer, the cycle will enter a neutral weather period, with a La Niña forming in the later summer into fall. This could lead to lower temperatures and normal to high levels of precipitation.

Even with a La Niña, Iowa can expect temperatures to continue breaking records and drought to persist with some areas in Iowa missing a full year’s worth of precipitation over the four years of drought.

“We’re going to need several months if not more than a year of above-average precipitation to really start busting the drought,” Glisan said.

Sarah | Mar 31, 2024 at 10:15 pm

Well written and thought-provoking.

James | Mar 19, 2024 at 8:22 am

I’m here to watch the climate deniers pile on like so many moths to a flame.