Replacement crops for corn and soybeans may be on the way, but in the meantime, climate, plant genetics and infrastructure determine what, and how much, Iowa produces in its many farm fields.

By optimizing Iowa’s farmland, global trade thrives and consumers get the most when they want it, according to Iowa State economists and agronomists.

“The current genetics that we have, it would be very difficult to be able to make major switches to crops right now,” said Bobby Martens, associate professor in economics. “Now, could you raise some other crops? You could raise them, but it doesn’t come close to generating the revenue per acre that corn and beans do.”

Martens also said global markets can cause prices to fluctuate over the coming years.

Genetic improvements have allowed corn and soybeans to thrive in Iowa, and a similar scientific change would need to occur to change crops, according to Martens.

“As climate change continues to happen, maybe we could see other crops become really important for the state of Iowa,” Martens said. “If things really change we could be raising a fair amount of wheat here one day, but we would probably need some genetic improvements to be able to do that.”

Mindy DeVries-Gelder, assistant teaching professor in agronomy, said the most realistic alternative crop might be wheat, though it would not be produced at as high of quality as other states, like North Dakota, might produce it.

She also listed tomatoes, strawberries, sweet corn and popcorn as crops that are grown in Iowa and fit annual harvest rotations.

DeVries-Gelder highlighted researchers at Iowa State who are researching more uses for mung beans, especially serving as a meat alternative, and millets because they are gluten-free.

Mung beans have been grown in Asia for hundreds of years but are now being introduced in the Midwest to diversify land management and improve farm income, according to the Iowa State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. The bean is used as a source of protein in vegetarian burgers, some kinds of pasta and cheeses.

Proso millet, a cereal grain requiring less water than corn, is grown with no nitrogen fertilizer and is harvested using the same equipment as corn or soybeans. According to the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, millet can substitute for most uses of corn, including ethanol and animal feed.

Gary Munkvold, professor in plant pathology/entomology/microbiology, stated in an email response that soil fertility and adequate rainfall allow for some possible alternatives such as sorghum, small grains like wheat and barley, many types of oilseed and biofuel crops, as well as fruits and vegetables.

An obstacle facing those alternatives’ viability and profitability is lack of disease resistance.

“Improved genetic resistance to fungal and bacterial diseases would help make these crops more profitable here,” Munkvold stated.

“Another issue can be quality,” Munkvold stated. “For example, barley for malting has strict requirements for grain composition, which are difficult to meet growing in Iowa’s humid climate with current varieties. Breeding barley malting varieties that are better adapted to Iowa conditions would potentially open up a valuable opportunity for Iowa farmers.”

Yield improvements, especially corn, have kept up with the rising cost of production, according to Munkvold.

The factors and advancements that brought corn and soybeans to where they are today are the same factors that need further addressed for the future of production, genetic resistance and environmental management.

“Genetic resistance to common diseases and pests has simplified management in the field,” Munkvold stated. “Transgenic traits for insect resistance have made corn production easier, more efficient, and actually increased the safety of the grain for consumption. Transgenic traits for herbicide tolerance have also increased production efficiency and lowered costs. Like all genetic resistance traits, these are tools that have to be carefully used, and that has not always happened.”

Barriers

The lack of a developed market for alternative crops like sorghum, wheat and barley also can prevent large quantities from being produced in Iowa.

“This is a self-reinforcing cycle; because the grain market has adapted to the predominance of corn/soybean production, the production system has become locked into feeding the existing marketing infrastructure,” Munkvold stated. “Some other crops like fruits and vegetables require much more labor (more expensive to grow) and the markets aren’t big enough to plant on the scale of corn and soybean.”

Inertia may stop farmers from switching away from the two staple commodities, according to DeVries-Gelder.

“Once I know how to grow something and do well at it and I can make it profitable and I’m doing that, it’s hard to change. Or, if you’re a new grower it’s really hard to come and do something that is very different than the rest of the system,” DeVries-Gelder said.

There are barriers to switching crops, too, according to DeVries-Gelder.

One of the primary struggles would be the new infrastructure needed to accommodate new crops, which is currently set up to accommodate corn and soybeans. Infrastructure includes aspects of production such as storage and combines and other equipment needed to plant, harvest and distribute a new product.

Markets, year-round desirability and crop insurance options may also deter farmers from producing crops outside of the two main commodities.

“We are used to having access to what we want when we want it,” said Chad Hart, professor in economics. “When you think about food production systems, they don’t fit that.”

Hart said although Iowa produces one round of crops per year, consumers still expect to see all products on grocery store shelves no matter what time of the year they shop, especially fruits and vegetables.

By focusing on comparative advantages, land can be used to its full potential to trade for a high value for products best made elsewhere, Hart said.

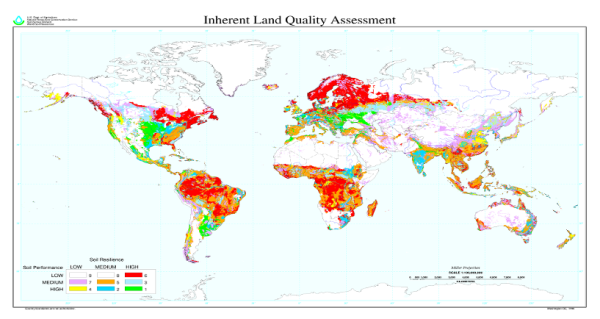

“Global trade is basically a way to connect those folks because…not everybody has access to the same soil,” Hart said. “[The green spots on the inserted map] have those soils that can produce those large crops; they concentrate on that. Those other areas concentrate on whatever they do best,” including labor, technology or tourism.

DeVries-Gelder said Iowa farmers would face more variability if they planted crops such as tomatoes.

“We couldn’t compete in production with like the central valley of California, as far as when you think about how much we could produce and where. We would have some issues with the timing of our rainfall and our temperatures, that some years it would work really well, no different than my garden,” DeVries-Gelder said.

Instead, Iowa farmers aim to produce more stable crops that fit the climate at high yields and trade for other products Iowa farmers can not grow as heartily.

Munkvold stated more frequent droughts and severe weather can damage crops, which leads to increased disease and pest pressure. Soil erosion is another factor in the future of farming.

“Soil erosion is deteriorating the fertility and quality of Iowa soils and is not adequately being addressed,” Munkvold stated. “This increases input costs and potentially reduces return on investment, not to mention the environmental costs.”

The story of corn and soybeans coming about are different, according to Munkvold. Corn has been around longer than soybeans as a predominant crop, with soybeans gaining popularity when farmers needed a rotation crop to be grown on large acreages.

The factors leading to corn and soybeans’ longevity as prominent crops have to do with labor, storage and land fertility.

“Other factors include the fact that production of these crops has been highly mechanized, so the labor needs are minimal, and the crops are easily stored for relatively long periods,” Munkvold stated. “Other crops like vegetables are more difficult to store and transport while keeping them in good condition. Iowa has excellent soil fertility and topography (relatively flat) for growing crops on large acreages, lower land costs compared to the eastern states, adequate rainfall (usually) compared to the western states and lower disease and pest pressure compared to other parts of the U.S. such as the south.”

ISU An Sci '83 | Mar 24, 2024 at 11:33 am

Greater diversity in Iowa agriculture would be ideal but isn’t practical in the short-run.

As mostly referenced but not emphasized, the situation is largely a function of

1.) available markets established for corn and soybeans,

2.) federal government incentives and safety nets from crop insurance to price protection programs (in which lenders require borrower participation), and

3.) futures markets for pricing (utilization of which lenders require larger borrowers).

Until these factors change, there’s too much risk & insufficient potential reward to change.

Joe Vignaroli | Mar 24, 2024 at 9:38 am

No disrespect intended, but Martens has it all wrong. Iowa had some of the richest soil in the world until most of the farmers turned to GMO seeds. GMO (genetically modified organisms) is what Marten refers to when he says Iowa farmers would need other crop seeds to be modified for use. It simply is not true.

GMO is the worst thing we as humans have done to our soil. GMO seeds lock farmers into buying all seed from GMO producers. Why? Great question. GMO crops produce their yield one time, that’s it. Farmers cannot allow a portion of their GMO crop to go to seed for use in the following season, as plants were designed. Rather, seeds from a GMO crop, if planted, will not bear its fruit, flower, etc. Now isn’t that odd? If the plant can’t reproduce itself as designed why does the human’s design keep that from happening? One word, profit.

And worse yet, GMO seeds do not prevent insect invasions or plant disease. They make it worse. GMO seeds require more and more pesticides that kill the organisms in our soil. They kill the earthworms, nematodes, arthropods, etc that help build soil and assist plant growth. When the soil is unhealthy our crops are easy targets for pests and disease. Plant diseases in turn require the use of Herbicides which, like Pesticides, kill our organisms in the soil. Thus, GMO turns soil into dirt.

Unlike soil that is healthy and thriving with organisms, dirt is lifeless. Dirt requires more inputs (pesticides and herbicides) for the plants to grow along the while continuing the death of our precious soil.

No, Marten has it all wrong but I am sure he is simply not aware of how soil works. Iowa farmers that go back to farming in concert with nature flourish more than their chemically dependent neighbors. Iowa soil can grow anything their four seasons allows, and those crops will fourish!

Shannon Claborn | Mar 24, 2024 at 4:07 pm

This comment is one of the most uninformed comments on GMO‘s that I have ever read. Most of his comments on GMO are flat lies. One specific, GMO, Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) DOES significantly reduces insect damage from some of the major corn pest of the Midwest, such as corn rootworm, corn borer, corn earworm, and western bean cutworm. All of these can significantly reduced yields and impact grain quality in terms of grain mold.s. Also, Bt is actually a bacteria that you can find in all soils across the Earth, so it returning back to the soil in the form of the plant residue or grain has no negative impact on soil health. This Bt GMO only kills these pests specifically so no earthworm, nematodes, arthropods, etc. are harmed by this or any other GMO. Also, no GMO claims to reduce crop disease. Crop disease is managed, primarily by crop rotation, foliar fungicides, and crop genetics that have better disease tolerance to major diseases in the Midwest develop through traditional breeding methods. Herbicides ARE NOT used for disease control but instead foliar fungicides are used which have no impact on soil health. Soil across most of Iowa, or some of the most productive and healthy soils that can be found in the Midwest. The majority of the soils typically have 4% organic matter, which is one of the key components of good soil health, Where microbial and earthworm activities and water infiltration rates are optimal. It’s sad, some posters such as Mr. Vignaroli can spread such false claims about biotechnologies that are used farming today.

Okatonfarm | Mar 23, 2024 at 12:31 pm

I read enough of this article to realize they have no idea what they are talking about about. I have grown most of the crops mentioned and there are reason they are not growing in Iowa. If you want specifics reach out.

Dan Lefever | Mar 23, 2024 at 9:29 am

Lots of excuses for not growing a diversity of crops with crops for animals incorprated, which many Iowa farmers are already demonstrating can be done to great advantage. Including the most important a better ROI (rate of return on investment); with a potential of hundreds to thousands of dollars per acre instead of a few cents per bushel on corn and soybeans barely or not even covering production costs, without government subsidies. The most difficult may be identifying a market before to plant harvest a new trail crop planting. Anything that is consumed directly from the farm should have no problem selling locally in a food dessert like Iowa, (how many people do you know that consume field corn and soybeans directly from the farm)? A very easy starter is to grow winter and or summer covercrops to start soil health improvement and then begin harvesting seed from them to sell for other growers to begin their path to improve soil health and sequester carbon in the soil. With the increased need for cover crop seed , farmers can use it themselves or sell to other local farmers at a good price. Using covers will start improving water insoak, nearly stop erosion and with an increase in stable soil carbon (organic humus); esulting in more water storage, for drought resistance, and less fertilizer input. Then diversify the corn and soy plantings as markets develope for other higher ROI crops. Also you can potentially do on farm processing for value added or direct consumed crops such as potatos or milled grains/animal feeds. As this evolves the farm begins to regenerate local communities and you develope an agriculturally supported community, ala Will Harris of White Oak Farm in GA. To start you regenerative path listen to 100+ Advancing Eco Agriculture podcasts on YouTube.

Bill | Mar 23, 2024 at 9:21 am

This is an informative post that filled gaps in my knowledge about justifications for the two-crop system in the Midwest. Thank you.

The mention of soil erosion and its twin—runoff and industrial scale pollution of surface water—is a reminder of that critical concern in the Midwest. Here on the east coast we have used the world’s great estuary, the Chesapeake Bay as our toxic waste dump for centuries, beginning with the era of mill dams in Lancaster PA. To this day their remains are a signifiant source of phosphorous pollution through storm-induced scouring of legacy sediment fields. That, together with organic and inorganic nitrogen fertilizer mismanagement up to the present has put Lancaster County in the EPA crosshairs for reducing nutrient loads in the Susquehanna River and its network of tributaries.

Perhaps one solution would be to take a page from the organic/sustainable ag crowd and get serious about cover cropping.

Any solutions will probably require realistic decision-making about including the costs of environmental restoration and sustainable environmental health in the calculus of food pricing.