Content Warning: This review contains mentions of sexual violence.

Editor’s Note: This review has potential spoilers but I leave a good chunk of the narrative out for the prospective reader.

“Neither love nor terror makes one blind: indifference makes one blind.”

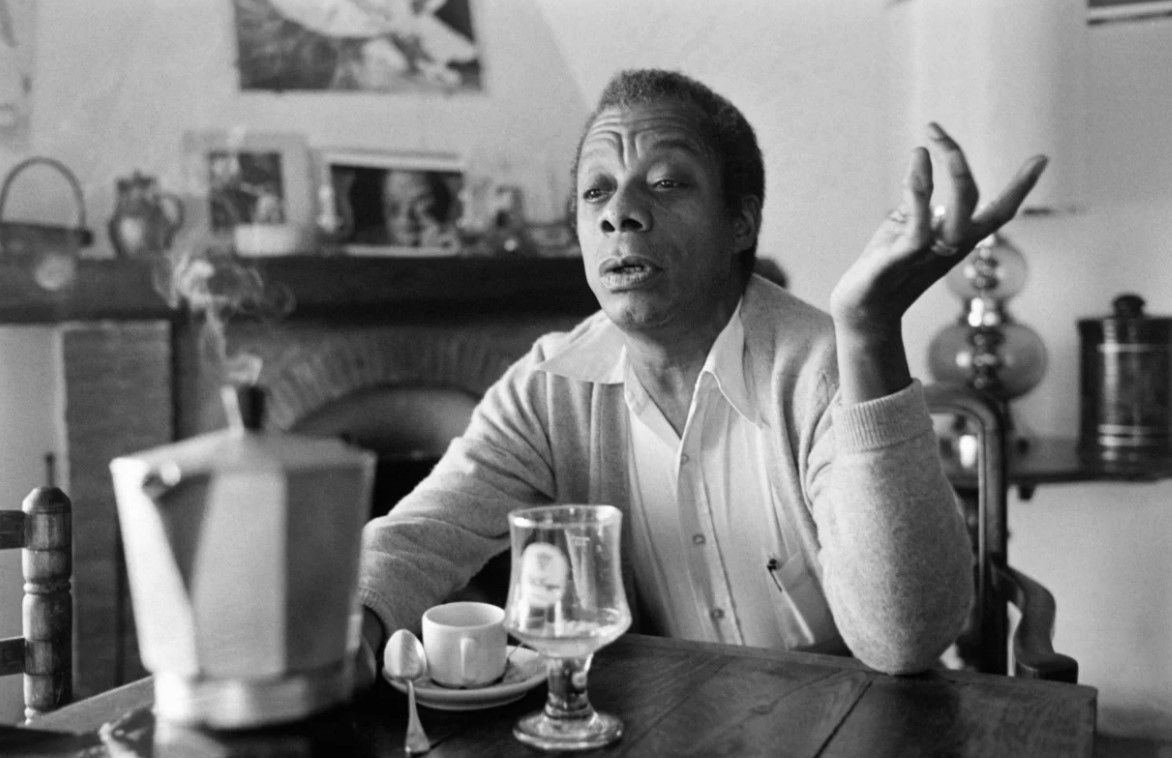

– James Baldwin, “If Beale Street Could Talk”

One reads a novel, or should, for the simple reason of life application. One ought to pick apart a book for that elusive and ever-generic term, “meaning,” which lingers around the contemporary conversations of literature just as much as it does when a relative discovers you have a tattoo. People always ask the same question: what is the point?

Baldwin’s novels always have a “point”—and unlike much of contemporary fiction, Baldwin is not watered down and cliche. On the contrary, his writing colors the page with a lively, pulsating rhythm and flow, not only pleasing to the aesthete but also for those searching for meaning.

“If Beale Street Could Talk” is the latest novel I read from Baldwin’s vast collection. It is about a 19-year-old Black woman named Tish (her actual name is Clementine) who falls in love with a Black man named Fonny (actual name Alonzo). The narrative centers on these two characters but also brings in both Tish’s and Alonzo’s families.

One day, when Tish and Fonny were at a grocery store, a menacing and predatorial man sexually harassed Tish. Fonny was not with her but was up the street looking for something else, reassuring Tish that he would be right back.

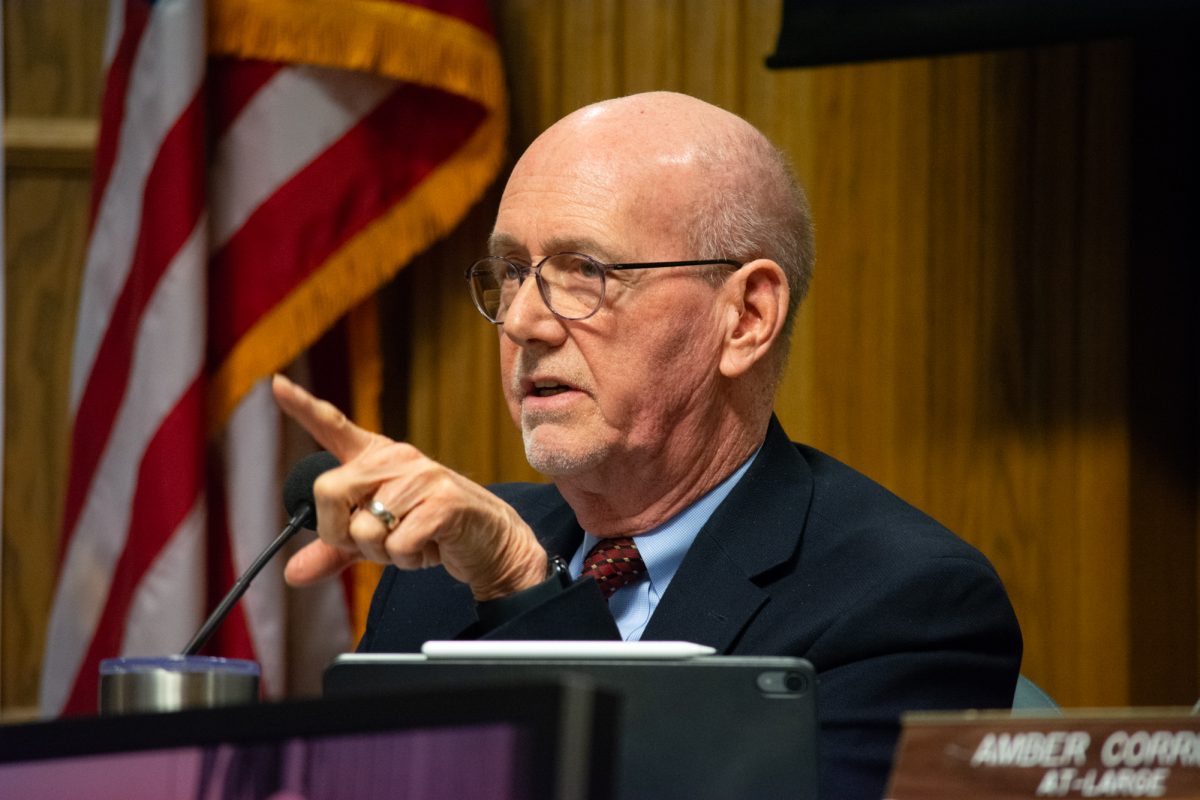

Once Fonny returns, he sees what is occurring and urgently intervenes, defending Tish against the aggressor. This causes quite a commotion, enough for Officer Bell to intervene. At this point, we begin to see the central tension of the book, which acts as a general theme across Baldwin’s books: that of the Black struggle, the tension between desired normalcy and bleak reality. Officer Bell ignores the man who forced himself on Tish and instead targets Fonny because he is Black, telling him that he will take Fonny to the station. It is only after the white grocer runs out and tells Officer Bell the truth that Officer Bell decides to let Fonny go. I describe this scene in particular because it provides context for the entire book.

Officer Bell wanted to get even with Fonny for being humiliated. After a woman, Mrs. Rogers was raped, Officer Bell claimed he saw Fonny running away from the scene. This obvious falsehood was made even more clear when Officer Bell placed Fonny as the only Black man in the criminal lineup after Mrs. Rogers said the perpetrator was Black. Officer Bell saw the opportunity for revenge and achieved it.

What follows is a story of hope and heartbreak. The novel shows the importance of family, of friendship, of love, of tragedy, of despair, of justice, of fairness and of truth. Baldwin never misses an opportunity to deftly describe the human condition, whatever that may be. He disintegrates the opinion that your own will single-handedly determines your fate and illustrates how some people and their hefty aspirations for self-determination are impossible if the odds of society are forever determined against them. However, this should never cause one to ruin themselves, to harm others, to contribute to an imperfect society.

As Baldwin writes: “I know about suffering; if that helps. I know that it ends. I ain’t going to tell you no lies, like it always ends for the better. Sometimes it ends for the worse. You can suffer so bad that you can be driven to a place where you can’t ever suffer again: and that’s worse.”

– James Baldwin, “If Beale Street Could Talk”

Reading Baldwin is always enjoyable and thought-provoking. Read all of him if you can.