What is more offensive to Americans than the outward claim that their minds are “coddled?” No. It can’t be. Americans are not so inane and tractable as to need coddling–a mere assertion that, as Christopher Hitchens writes, violates “the conservative belief in American exceptionalism.”

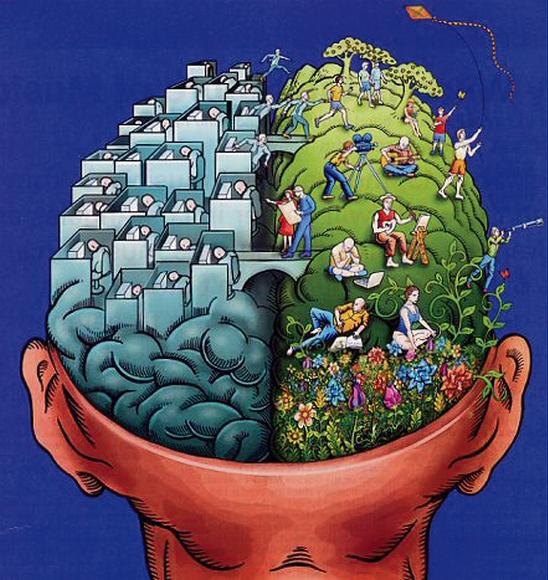

I referenced a great book by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt in my last article that deserves more scrupulous treatment. It also deserves the widest reading possible because it contradicts the idea of American exceptionalism. As a university student among thousands of others, “The Coddling of the American Mind” attempts to explain many perceived declines among American youth–“declines” being alarming increases of anxiety and depression, a proclivity to disengage from challenges and potential confrontation and parenting and institutional approaches that are probably doing far more harm to our youth than good.

The further claim lies in the subtitle: “How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure.” This claim advances the notion that many practices installed at institutions like universities are back-firing miserably and instead are reinforcing negative emotion and behavior while attempting to help it. The subtitle enlarges what I think people need to keep in mind when reading the book: the authors are not slandering anyone and do not have any frozen partisan bias. Many who read this sympathetic review and perhaps the book may disagree, but I think that would only reinforce the book’s core argument.

Since it covers a wide array of topics, I should like to engage in this article with what is most relevant to us on campus. Core to the book is the idea that three “Great Untruths” have spread and that they are easily found “on college campuses, in high schools, and in many homes.” More than that, “these untruths are rarely taught explicitly; rather, they are conveyed to young people by the rules, practices, and norms that are imposed on them.”

What are these Great Untruths? First is what they call the “Untruth of Fragility: What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.” In direct opposition to Nietzsche, one enlists this “untruth” when they believe that something adverse harms them in a dramatic, decisive and unalterable fashion. The next is the “Untruth of Emotional Reasoning: Always trust your feelings.” The idea that feelings are often misleading appears obvious enough, but upon further analysis – say, of a modern university campus – it clearly loses efficacy. In other words, there is no shortage of students, faculty and administrators who engage in this kind of reasoning and make being a student on campus an increasingly tense affair. The last untruth is simply the definition of tribalism; it is the “Untruth of Us Versus Them: Life is a battle between good people and evil people.”

It can be asked according to what standard do these untruths have any credibility and it is valid to consider such questions, of course. In the book, the authors assert three criteria for an idea to qualify as a Great Untruth. First, it contradicts “ancient wisdom (ideas found widely in the wisdom literatures of many cultures).” Second, “it contradicts modern psychological research on well-being.” And third, “it harms the individuals and communities who embrace it.”

Lukianoff and Haidt make the case that these untruths are pervading our college campuses and making it immeasurably more difficult for students to properly engage with the material they are learning and, more importantly, offer dissenting viewpoints and critique of such material. They present numerous cases of students embracing the three great untruths and worst of all, administration that does too.

In many of these cases, if a professor voices an opinion that offends someone, instead of the administration standing up for the right to free expression and inquiry, they often cave in to student demands and force the professor leave campus and academia with their tail between their legs.

This is not because, as many suggest, colleges have been conscripted and annexed by radical left-wing politics. Rather, as Eric Adler (a source also referenced in the book) writes:

“It is a market-driven decision by universities, made decades ago, to treat students as consumers—who pay up to $60,000 per year for courses, excellent cuisine, comfortable accommodations and a lively campus life.” In sum, kids are arriving on campus more anxious, more depressed, less inclined to challenge themselves and more likely to persecute perceived opponents – and the fact they pay a lot of money for it means many students think that is how it should be.

This is a novel viewpoint that many, including myself, failed to consider before. Furthermore, the book documents cases where both the political left and right have clashed and engaged in the three untruths, with especially sinister and frightening threats stemming from the political right. In short, Lukianoff and Haidt attempt to explain why it is imprecise to chalk up campus chaos to student adherence to left-wing politics. Without question though, radical politics plays some role, on both the left and right, creating a toxic blend where each side fails to move forward if it’s not at the expense of their opposition.

However, it hasn’t always been this way. When your parents or uncle or aunt shower you with the “when I was your age” cliche, the differences they often describe are generally true. Campuses have not always been so tense, even if they have always remained politically active. Lukianoff and Haidt explain that Gen Z (who they refer to as “iGen”) face higher levels of anxiety and depression than generations past and as our generation now fills the halls on university campuses, these correlations may hold the key to what many perceive as a padlock to progress on university campuses.

The increase in screen time and social media, the increase in helicopter and overprotective parenting, the sheltering of children to opposing views, the rise of “safetyism” in K-12 schooling and beyond, the echo chamber effect of the internet and the deliberate atomization of the population is all contributing to less prepared and less effective children. Lukianoff and Haidt present grueling and disheartening statistics on the state of our youth and if you care about answers to many of the happenings of our time, especially in higher education, then I can not recommend a more prescient book than this one.

Rating: 8/10

David Jackson | Nov 19, 2024 at 6:33 pm

First, excellent choice of a book to review and a one every college student should read to better understand what’s been done to their understanding of reality by the institutions they’ve grown up attending. That said, a couple of your points are off the mark.

“It also deserves the widest reading possible because it contradicts the idea of American exceptionalism.”

-Weingarten

How exactly does it do that? What leftist firebrands like Christopher Hitchens fail to realize is being too in love with their own voice makes them prone to falling for their own strawman fallacies. American exceptionalism is not a blind faith that every social tend in the US is of divine origin and America can do no wrong. Rather it is the fact the US is the only country in history founded on the idea of individual human liberty. Not an ethnicity, or a race, or a religion, but the republican ideals of a constitutionally limited government in which the state is run by representatives of the citizen body with the primary role to protect the peoples’ God given natural rights. This in contrast to legal privileges granted by a unconstrained governing body, which by definition could change its mind on what privileges it wants to allow you to have once it becomes inconvenient to those in power for you to have them.

“This is not because, as many suggest, colleges have been conscripted and annexed by radical left-wing politics.”

-Weingarten

Yes, it is. Adler’s point does not disprove the ideological annexation by radical left-wing politics at our universities. He simply points out the profit incentive universities have to keep students enrolling. Think about why students are arriving at campus “more anxious, more depressed, less inclined to challenge themselves and more likely to persecute perceived opponents” in the first place for a moment because it’s not a coincidence.

A) Is it because they’ve been educated in schools, taught by public school teachers with education degrees, to be emotionally resilient independent thinkers? OR

B) Is it because they’ve been educated in schools, taught by public school teachers with education degrees, to believe on the bases of moralizing appeals to emotion (Me-ology, SEL, etc.) while they’re too young and inexperienced to know any better, deconstructionist neo-marxist agitation propaganda (Privilege Theory, Critical Theory, DEI) telling them our society is a racist, sexist, exploitive, nightmare on the brink of “christo-fascism” that only exists to oppress most of them and they’re not allowed to question that? Could that possibly be a factor in the production of the coddled mind?