North Carolina State Professor Gives Annual Staniforth Lecture

April 3, 2018

Can genetic pest management protect crops, human health, and biodiversity?

This is the question Dr. Fred Gould tackled on Tuesday night’s lecture in Curtiss Hall.

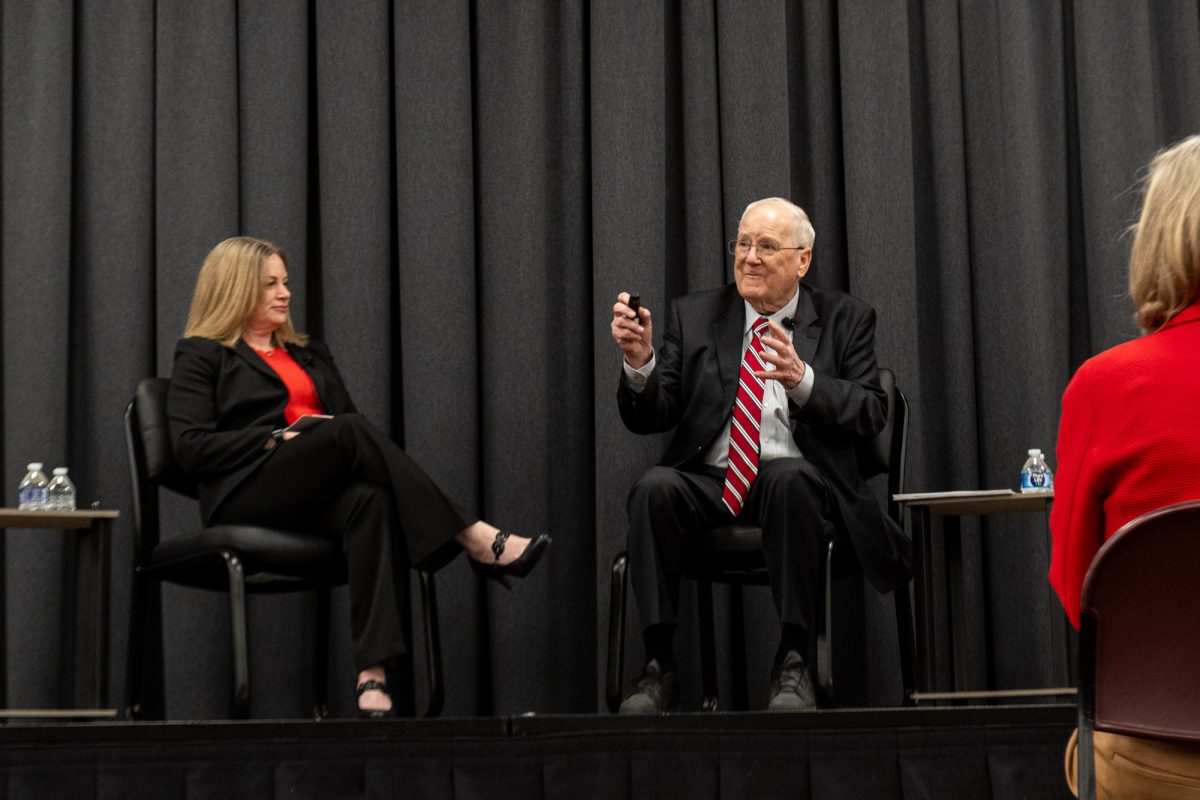

Dr. Fred Gould, University Distinguished Professor and Reynolds Professor of Entomology at North Carolina State University, presented the 29th annual David W. Staniforth Memorial Lecture on genetic engineering Tuesday night. The purpose of this lecture was to examine concepts and history of pest management, the potential impact of advances in the field, and the intersection of ecology, genetics, and public values.

“This topic of genetic engineering is very important to the general public,” said Mike Owen, Associate Chair of the Agronomy Department at Iowa State University. “You can get people who are really opposed to it, and you can also get the agricultural perspective on it and its benefits.”

Owen went on to explain the difference between the topic largely debated in media, and the topic of Tuesday night’s Staniforth lecture.

“This lecture is not about crops, it’s about pest management,” Owen said. “With genetic manipulation, there is no need for insecticides, and has the potential to be a great solution down the road.”

Dr. Gould started the lecture out by giving an example of pest management. He described how the genes in a mosquito were modified to interfere with the Dengue virus it was carrying.

“Pest management is not a new idea, but the tools we have now are far different than the ones years ago,” Gould said.

Gould explained that the process of removing a pest from an area is done by the “9:1 ratio.” This means that for every one pest, there are nine genetically manipulated pests. This ratio leads to the extinction of that pest within a matter of time. One example given in the lecture was the screwworm fly. It all started on Sanibel Island in 1953. The ratio was used to get rid of the screwworm flies in that area, which led to the savings of $1.5 billion per year.

The studies of molecular biology are extremely helpful in examining genetic engineering. Molecular biology produces more genes, manipulation, and mechanisms, but also more social concerns.

“People have this idea that scientists don’t think about the consequences, release lots of genetically manipulated pests, and get rid of the entire species,” Gould said.

However, there is a lot of research and planning that goes into genetic engineering and manipulation. Researchers take a lot of time to study the genes and different forms of manipulation so the results will continue to improve.

So, can genetic pest management protect crops, human health, and biodiversity?

“There is no exact answer to this question,” Gould said. The question posed at the beginning of the lecture cannot be answered with a simple yes or no.

“I’m very optimistic about the future of genetic engineering,” Gould said. “I can see it being a successful tool in the future.”