Lawyers talk history and shortfalls of Brown v. Board of Education

Pearson Hall will host “Changing Perspectives,” an event to raise awareness for physical disabilities out on by International Student Council.

April 19, 2018

Two lawyers, one case.

When speaking of Brown v. Board of Education, the case that aimed to put an end to segregation in schools, one spoke of the history and its importance; the next brought to light its shortfalls still seen today.

Attorneys Husanne Muhammad of Justice Law Firm and Tim Gartin with Hastings, Gartin and Boettger spoke to a classroom of 14 people at 6:30 p.m. Thursday in Pearson Hall.

Brown v. Board of Education was an historic Supreme Court ruling that state-sanctioned segregation laws were in violation of the 14th Amendment.

Husanne Muhammad is a native Iowan from Waterloo and graduate of Iowa State. She was brought to speak by her daughter, Meccah Muhammad, junior in public relations and a lifestyle reporter for the Iowa State Daily.

“[My mother] is part of the reason why I’m so open minded myself. I really have a passion for justice too and I get that from her,” Meccah Muhammad said. “She encouraged me to think about my own community differently and think of other communities in a more broad prospective.”

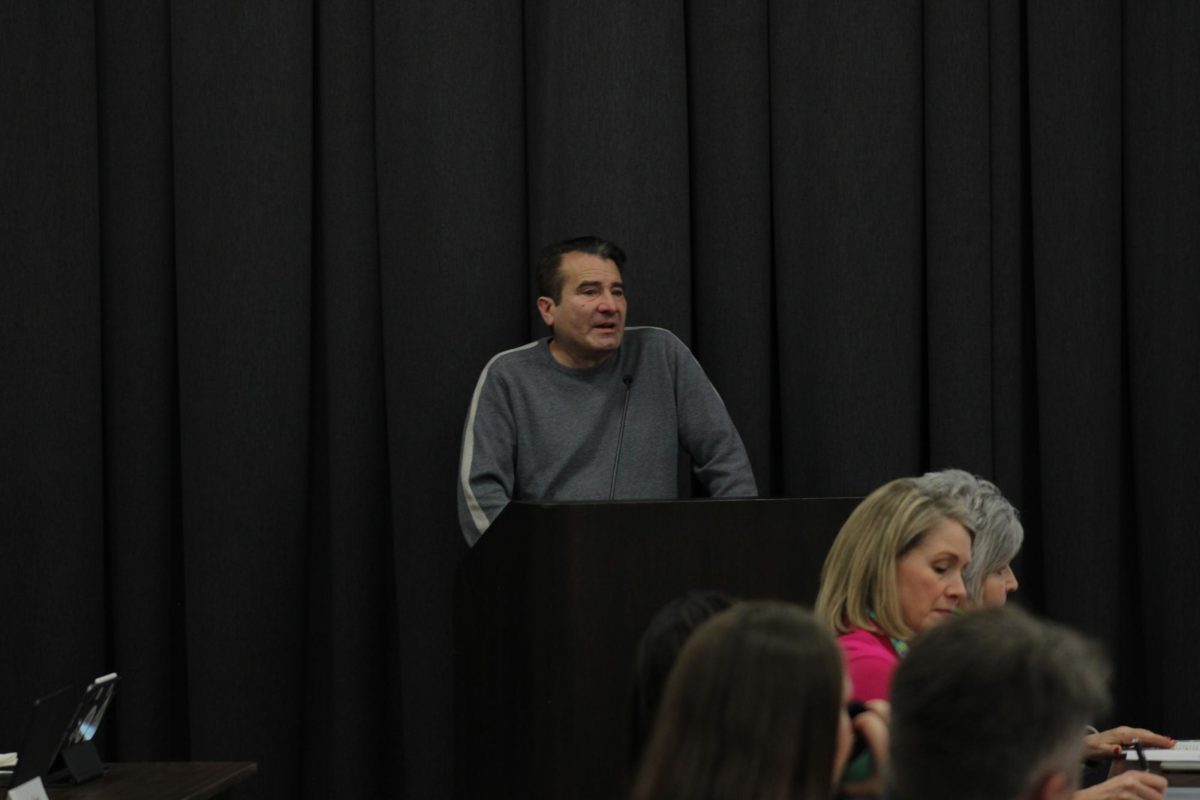

Gartin, who is a member of the Ames City Council and received his doctorate from Iowa State, spoke first giving a background to Brown v. Board of Education.

Gartin started with an anecdote. As he researched for this presentation putting many hours into it, his wife asked him why he was so obsessed with this case hoping to better understand its importance.

After taking the night to think about it, Gartin came back with three reasons why this case is important.

First, he said it is the most important case of the 20th century, adding that those who wish to study law must have some understanding of this case. Second, he said the struggle for civil rights is not over.

Gartin said the way something like the Battle of Gettysburg is studied is different from the way Brown v. Board of Education is studied “because that war is over.”

Last, he said it is important to know the good and bad of America’s history.

To do this, he encouraged attendees to read the books “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” and “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.”

When Husanne Muhammad spoke, she brought what she thought were the two main issues with Brown v. Board of Education.

First, Husanne Muhammad said the ruling did not go far enough with integration. She brought up definitions of integration including one that said it was a “harmonious or integrated whole.”

The discrimination that continued in American schools contradicts this definition.

Second, she said “both sides are being miseducated.” She spoke of her own education at Valley High School in West Des Moines where she was the only black student.

She remembers being embarrassed of her history. As students learned of white presidents and adventurers and inventors, all they ever heard about black history was slavery and civil rights.

Later she would learn of the history that was left out of her education.

“How did we do that in the condition that we were in?” Husanne Muhammad said.

Thinking to her education, she said if she were Caucasian she would think her people accomplished everything creating a further disconnect with other races.

“Even my concept of God was white,” Husanne Muhammad said.

To start looking at the history of Brown v. Board of Education, Gartin stressed the importance of the 14th Amendment.

“No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States,” the amendment states.

Gartin said this amendment has been debated heavily throughout history stating, “we are still trying to figure out what that means today.”

The 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson led to a new wave of segregation laws in the south known as Jim Crow laws.

“These laws were put in place by almost a systematic form of terrorism by lynchings all over the south,” Gartin said. “So people talk about terrorism as something far away. This country has experienced, black people in the south have experienced systematic terrorism.”

Gartin spoke of two legal terms that are necessary when understanding Brown v. Board of Education: de jure segregation (Legal segregation), de facto (separated by fact).

Brown v. Board of Education ended de jure segregation, but de facto, where populations are segregated by different factors, is still prominent in the United States.

Linda Brown was the center of Brown v. Board of Education.

The father of Brown, a carpenter in Topeka, Kansas, spoke up after growing tired of seeing his daughter’s long commute despite a white school’s close proximity. Schools were relatively equal in quality and only segregated the elementary school level.

Unlike past cases, the parents argued against the idea of segregation rather than inequality of quality on the basis of the 14th Amendment.

After two unanimous rulings and much resistance, the ruling ended de jure segregation in the United States, though it did not solve race issues in the U.S. as they persist today.

Husanne Muhammad spoke to the bullying and discrimination children faced as schools were integrated asking that with bullying being the issue it was today, could people imaging what it was like for these black students.

She brought up that adults also showed disapproval in their presence.

“It was like going into a war zone,” Husanne Muhammad said. “It was like sending your children into enemy territory.”

She brought up the doll test which demonstrated the effect racism had on black children.

Children were shown two different dolls who only differed by the color of their skin. When asked which doll was good or nice or pretty, black children pointed to the white doll.

Husanne Muhammad said this is still a reality black children face in 2018.

She attended Valley High School in West Des Moines and feels both grateful for the quality of education but traumatized by the experience of being the only black student.

Black students still have the lowest high school graduation rate, Husanne Muhammad said. Only half of the black students at Iowa State will graduate in six years.

Black students are four times as likely to be suspended or removed from class.

Black Iowans make up 3.3 percent of the Iowa population but 25 percent of the state prison population.

She called it “an intentionally broken system.”

“It’s been around for several generations. It’s not new,” Husanne Muhammad said.

She said people have to go much deeper than slapping down laws that may be overturned and gutted telling the audience, “Don’t be limited by a statute and a law.”

This event was put on by the Iowa State chapter of NAACP and was organized by Joy Kimani, the director of programs and freshman in management information systems.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated due to an error. Both Waterloo high schools have similar black student enrollment showing no evidence of de facto segregation. The Daily regrets this error.