When King Came to State: Martin Luther King, Jr. Day

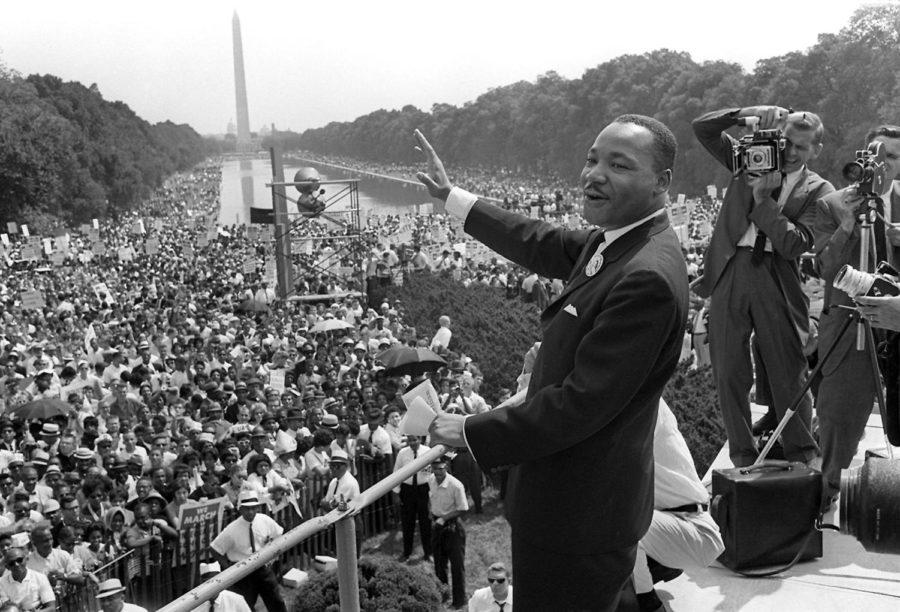

Photo courtesy: AFP/Getty Images

US civil rights leader Martin Luther King Junior waves to supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963 on the Mall in Washington DC during the March on Washington.

January 15, 2018

The preparation was no different than usual for the 1960 “Religion-in-Life Week” at Iowa State. However, the organization managed to have one of the most talked about religious figures speak at Iowa State: Martin Luther King Jr.

For the now-defunct Student Religious Council at Iowa State, the organization’s “Religion-in-Life Week” was the largest yearly project.

At 31, King was already one of the most recognizable civil rights figures in the United States. He had received his doctorate. He had already been a leader of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in late 1955 and 1956.

King’s activism in Montgomery, Alabama began after the arrest of Rosa Parks in 1955. Although, he had already had a letter to the editor demanding equality published in the Atlanta Constitution in 1946, following his sophomore year at Morehouse College.

King was on the cover of Time Magazine in February 1957. King met with both President Richard Nixon in 1957 and President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1958.

In March 1957, King met with Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah of the new nation of Ghana during their independence celebrations. In February 1959, he went to India and met with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as well as Gandhi’s followers.

Not all were welcoming of King’s message of equality and social and economic justice. His home was bombed on Jan. 30, 1956 while he was at a mass meeting at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. His wife Coretta Scott King and infant daughter Yolanda Denise King were inside the house, but neither were injured.

In January 1957, King was named the chairman of the Southern Negro Leaders Conference on Transportation and Nonviolent Integration, now known as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

King had achieved international notoriety and changed the world but he still found time to speak to the students of Iowa State.

King joined Vaclav Hlavaty, a mathematician, and O. Hobart Mowrer, a psychologist, in speaking during the week. King closed the week with his speech on Jan. 22, 1960. According to the Ames Tribune, around 1,500 people crowded into the Great Hall of the Memorial Union and overflowed into the South Ballroom and balcony to hear King speak.

Latecomers were moved to the commons in the Memorial Union and had to listen to King’s speech over loudspeakers.

Speaking on “The Moral Challenges of a New Age,” King opened his speech by telling the audience about his time in Africa, when Ghana had become a nation and gained its independence from Great Britain. By seeing the British flag lowered and the new Ghana flag raised, King identified the issues to be colonialism and imperialism, however, he compared the issues to the segregation and discrimination being seen in 1960.

“We have seen the old order in our nation in the form of segregation and discrimination,” King said. “Since 1619 when the first slaves landed here, against their will, a year before the Pilgrims came.”

King touched on economic inequality and called for solidarity among all people, regardless of their standing or power in society.

“All I am saying is simply this: All life is interrelated, whatever affects one individual, whatever affects one nation directly affects other individuals and other nations indirectly,” King said. “We are all tied in a single garment of destiny, we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, and therefore, we must live together.”

King held a firm belief that injustice and suffering that affects some must be seen as affecting all. His statements at Iowa State reflected this.

“So long as there is poverty in the world no individual can truly be rich, even if he has a billion dollars. So long as diseases are rampant and millions of people cannot expect to live more than 28 or 30 years, no man can be totally healthy, even if he has just got a checkup from the Mayo Clinic,” King said. “Strangely enough, I can never be what I ought until you are what you ought to be. This is the way life is made, this is the way the universe is made.”

King’s speech did not shy away from addressing racism and the pervasive presence it maintains in society. He did so in a predominantly-white land-grant university, the exact type of institution King believed maintained white supremacy and economic stratification that harmed people of color.

King said that even though the Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in 1863, it only “established him as a legal fact but not a man.”

“We stand on the threshold of the greatest era of our time in race relations,” King said.

King spoke of how violence had been used throughout history in revolutions. King advocated for non-violence, not wanting to take the traditional route.

“The negro must not defeat or humiliate the white man, but must gain his confidence,” King said.

“Black supremacy would be as dangerous as white supremacy.”

King told the audience that he was not interested in rising from a position of disadvantage to one of advantage.

According to the Ames Historical Society, King also discussed filia — the affection between personal friends — particularly agape, the spontaneous love one may have for another without an ulterior motive.

King called the feeling “an overflowing love” and said that people extend the love to one another because they recognize it as the love God shows his people. King believed this was the kind of love that should be shown, especially during times of struggle, and it became incorporated with the non-violent approach which he would continue to use as a tactic to achieve civil rights legislation.

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968 at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. King had been organizing the “Poor People’s Campaign,” addressing economic inequality across all races and backgrounds. The movement advocated for increased wages, access to education and food for low-income people through legislative organization and mass civil disobedience.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day was federally recognized as a holiday in 1983, although some voted against the establishment of the holiday. Some of those who voted against the holiday are still in government, including Chuck Grassley, R-Ia., John McCain R-Az., Richard Shelby, R-Al., Orrin Hatch, R-Ut., Hal Rogers, R-Ky. and James Sensenbrenner, R-Wi.