Editorial: In 2017, why are we still blaming victims of sexual assault and harassment?

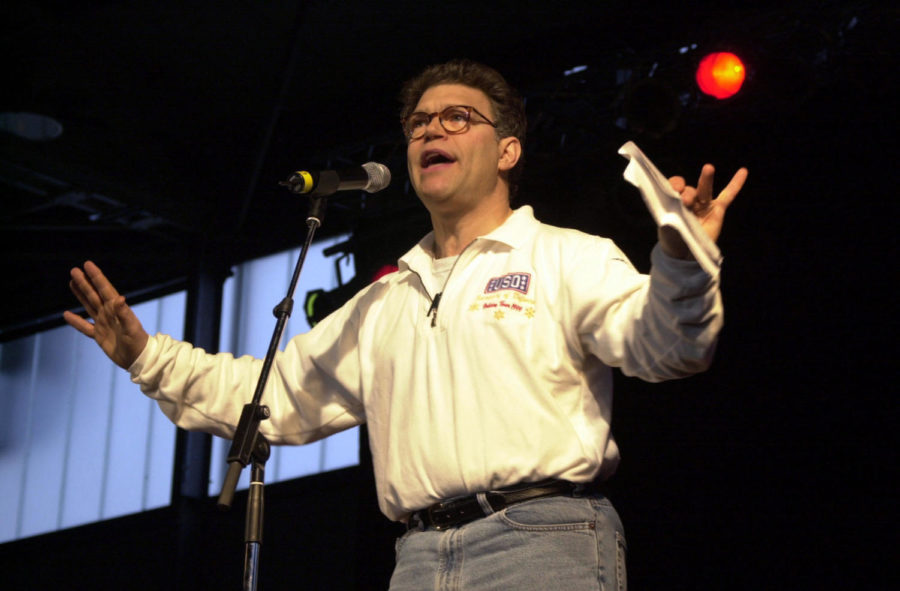

Photo Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

001217-F-2454T-543

November 21, 2017

In 2017, why are we still asking if someone who reported being sexually assaulted was drinking or what they were wearing?

In 2017, why are we saying allegations of sexual misconduct from years ago are somehow fishy because of the timeline of when it was reported?

In 2017, why are we still saying parents not monitoring their kids’ online behavior is the reason children are being lured into a sexual predator’s trap?

In 2017, why are we still defending predators as good people and finding it hard to imagine they’d ever do anything like that?

Because, as far as we are concerned, none of that should matter.

Despite what the survivor was wearing or drinking, it is still the perpetrator’s fault. Despite allegations being made years after misconduct, it is still the perpetrator’s fault. Despite parents not monitoring their kids’ online behavior “closely enough,” it is still the perpetrator’s fault. And despite finding it hard to imagine someone we know could do something so horrible, it is still the perpetrator’s fault.

When discussing sexual assault and harassment, it is of the utmost importance that we don’t place any blame on those who are reporting. This doesn’t mean we don’t promote personal safety or bystander intervention — because we should. But first and foremost, as a society, we must make it understood the action of sexual misconduct itself is horrible and the person or persons who enacted the misconduct are to blame.

We must make sure consent is understood. And we must make sure that by no means is it funny, as Sen. Al Franken must have thought it was, to make fun of sexual assault.

President Donald Trump spoke out against Franken and the allegations he faces.

Those tweets are, simply put, hypocritical and sick. The man who is the leader of our nation dismissed a tape of himself glorifying groping as “locker room talk.” What Franken did was wrong. What Trump did was wrong. What any perpetrator of rape, sexual assault or sexual harassment did was wrong.

Last week, allegations of sexual misconduct surfaced about Charlie Rose, a well-known American broadcaster. His CBS colleagues responded in the best way you could to such a horrible situation.

“Let me be very clear: There is no excuse for this alleged behavior. It is systematic and pervasive,” said Norah O’Donnell, who is a co-host of CBS This Morning, which Rose was a part of before being suspended by CBS. “This has to end. This behavior is wrong. Period.”

This is how we should respond to reports of sexual misconduct of any form. We should always place the blame on the action and the person or persons who conducted that action.

Campaigns to look at:

- Iowa State Police’s Start By Believing campaign focuses on believing those who confide in you that they’ve been assaulted.

- The #MeToo movement showed, and is still showing, how widespread a problem this is. But, it’s also important to note not every person who has been harassed or assaulted spoke up. After all, the victim blaming culture we live in, isn’t the best atmosphere to speak up in.

- Don’t be That Guy is a campaign that seeks to inform about consent. The campaign’s page states, “typically, sexual assault awareness campaigns target potential victims/women by urging women to restrict their behavior. We know through our work at Battered Women’s Support Services and research confirms that women are, on a daily basis, taking remarkable steps to prevent victimization, and that targeting the behavior of victims is not only ineffective, but also contributes to how much they, the offender and the larger public (including law enforcement and justice system) blame women after the assault.”