‘Every day I’m terrified’: Hugo Bolanos’ story

November 24, 2017

This piece is part of a series about people in the Iowa State community who are affected by the decisions the U.S. Government makes about the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Put into place by the Obama administration in 2012, DACA protects undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children.

On Sept. 5, 2017, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Trump administration would rescind DACA, with a six-month delay for Congress to act. If legislative action does not occur, recipients, also called Dreamers, may lose their protected status beginning March 6, 2018.

The following passages, save the first paragraph, are those of Hugo Bolanos and have been edited and condensed for brevity and clarity.

Hugo Bolanos, a 2017 graduate from Iowa State in journalism and international studies, arrived in the United States with his aunt and cousin in May 2000. He started school that August, attending Crestview Elementary in Clive, Iowa.

“

I was born in Michoacan, Mexico and I lived there for about six years and my mom and dad, they were gone from about age 4 to 6 and it was just my sister and I in Mexico. She was taking care of me, she was about 12 and the reason because is my mom and dad were in the States, they were working, trying to get enough money to take my sister and I over.

At the time I didn’t really know what was going on, it was just sad because I didn’t know why I was just with my sister. Eventually my mom came back, she told me that we’d be going to the States and I was happy.

I tried making friends as soon as I got here, but I didn’t know any English so I tried playing some games with some of the kids, but the way you play games in Mexico is completely different than the way you play here.

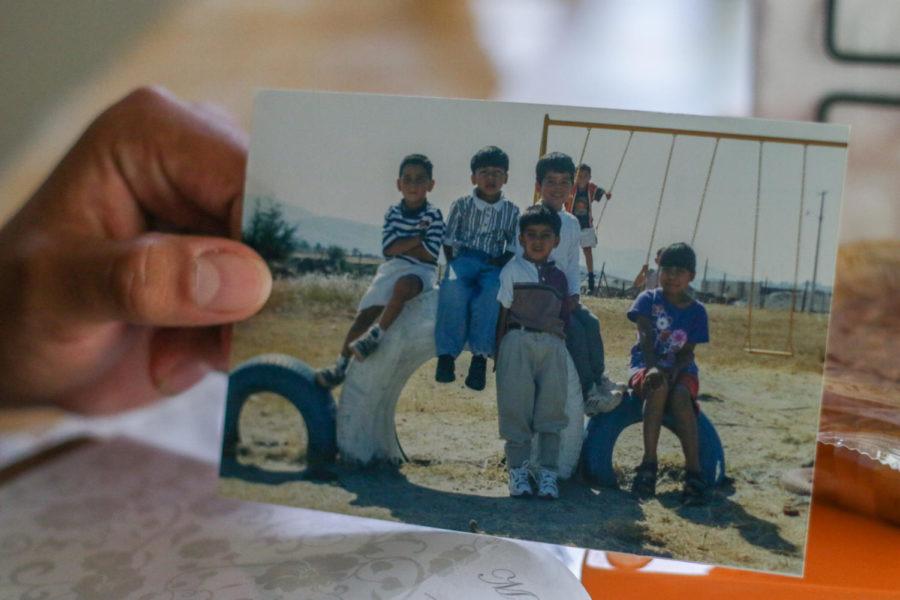

In Mexico you don’t have much of a playground, you maybe have some swings and then that’s about it. But in Mexico I remember, as weird as it sounds, we’d throw rocks at each other and you try to dodge them and it would be kind of like dodgeball.

I remember I came to first grade and the first recess, I was like “OK, I don’t know what’s going on, I’ll just try and make friends” and there was this rock climbing wall with some rocks at the bottom just in case you fell and I remember I grabbed some rocks and threw them at some kids to initiate “Hey, do you want to play?” but I remember I got in trouble and I would get rule slips. It caused my parents to get even more mad at me and I didn’t know how to defend myself because I didn’t know English so after a while I was like “OK, maybe throwing rocks isn’t the best idea.”

***

[Life in Mexico] was horrible. I remember my dad, when we first arrived here he would always bring up ‘Oh, you gotta appreciate what you have here in America, you gotta appreciate every little thing down to the food, to the clothes, to just enjoying another beautiful day in air conditioning’ and he would always tell me stories about how when he was growing up he didn’t have much to eat, he would just eat tortillas with salt, and that was it.

And he would always remind me of how he didn’t have much underwear, just because he didn’t have much money to buy it so he would wear the same underwear for more than two days. And I thought that was pretty nasty, but it just made me realize, damn, shit was tough.

He said that he would get holes in his shoes and he would have to sew his clothes and it was just really bad. My mom also mentioned that when my sister was born, they would have to use the same diaper, just trying their best to clean it out and use the same diaper all over again.

That’s not something you really imagine, it’s just really scary to think about, compared to how we’re living now.

I think ultimately my parents made a great decision coming here just because we live so much better. To me, I think they’re wealthy even though we don’t have the most money.

***

Once you come, you have to stay. If you do go back wherever you’re from, they’re going to make sure you stay there. My family and I of course, we want to go back and visit our family members, but there’s no way we can stay there for the rest of our lives. It would really be extremely difficult because we’re accustomed to the American culture. The food is different, the living situation is different, so honestly, I don’t think I would be able to live in Mexico because I’ve been here 17 years of my life.

On top of it, I have so much going for me here in the States that I don’t think me going back to Mexico is the best thing. I think I have the possibility of achieving my dreams here and that’s why I want to stay here, just because I have so much that I can give not only to the country, but to myself and my family.

Now that Trump has gone with what he said and from now until March is just kind of a waiting game, so every day I’m terrified. Every night I pray and thank God for giving me another day here and hopefully the next day can also be in the States.

A week in my shoes is just knowing that you’re going to have to wake up and think about this and sometimes when you hear the door knocking, it could be your last day, or sometimes when you’re eating with your family, it could be the last meal you have with them. Sometimes when you’re driving, it could be the last time you’re driving down that street.

It just hurts because you never know when your last day’s going to come and also you want to show people that you’re not a bad person, you want them to understand what you’re going through and also see the way that you do it because there’s no reason for DACA to be gone. It’s helped so many people and those people have really done nothing but good for this country.

***

My senior year, I was undocumented and so after my senior year there really wasn’t much else I could do except find a job that would be willing to pay me for labor or something. So I just thought the rest of my life would just be about labor and just crappy jobs.

So then I was really depressed my senior year because I knew it was my last year in school and I knew I didn’t really have anything going for me after high school because I couldn’t’ really go to a university or anything.

Then Obama passed DACA and it just opened my eyes. I applied and couldn’t believe this was actually happening so I was like “okay, I’m not going to get my hopes up until I have my social security and my work permit in my hands, that’s when I’ll believe it.” And sure enough, they came within six months or so and I was ecstatic. As soon as I got it, I applied to [Des Moines Area Community College].

[When I graduated from Iowa State], I started crying as soon as I walked up the stage and sat down because I realized that what I came here for was because my parents wanted a better future for me. Just having the moment of walking through the stage and living in that moment, it’s going to live with me for the rest of my life.

And I remember just breaking down and crying in my chair because it was just something I never imagined would’ve happened and I never would have thought the opportunity of going to a university was ever possible until DACA.

So it’s just achieving those four years of university and finally realizing that I had accomplished something much greater, not just for myself, but for my family just made me get all emotional and made me realize that everything was taken for granted until that moment.

I try to be a positive person and I try and just make every day like it’s my last so if you were to see me today as my last day, it’s kind of like ‘oh he was always happy, he was always joyful’ and that’s what I think about every day, just making everyone seem like they matter and making everyone see that there’s always going to be problems, but there’s always good things to look forward to you.

“

If anyone would like to share their story about DACA with the Daily, please reach out to [email protected].