Part five: Unsolved

January 28, 2022

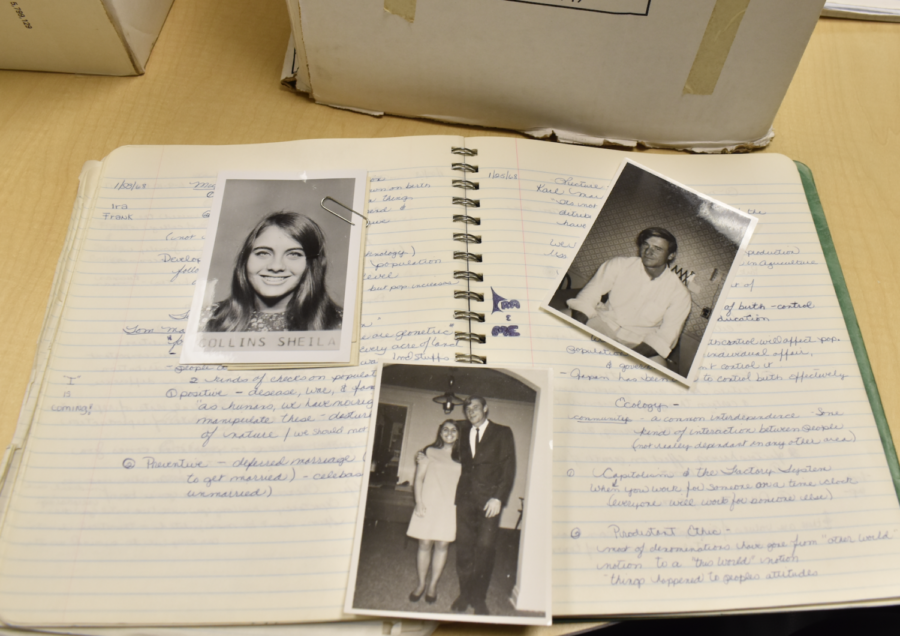

Editor’s Note: This article is the final part in a five-part series telling the story of Sheila Jean Collins, an Iowa State student who was murdered in 1968. Part four can be read here.

Content Warning: This article contains mentions of sexual and physical assault.

A half-century has passed since Iowa State freshman Sheila Jean Collins was murdered, and investigators today have found themselves at a standstill.

“I think it was a lot of little things that came together,” said former Story County Attorney Mary Richards. “You know, not one big thing, but a lot of little mistakes or oversights…and not maybe seeing possibilities.”

Lack of technology, jurisdiction issues, errors in evidence collection and politics each had lasting effects on Sheila’s case.

The first challenge started as soon as the body was found. Investigators needed to determine which law enforcement agency would be responsible for the investigation.

“It sounded like it was a big, for lack of a better term, cluster — back when it happened,” said Anthony Rhoad, the current investigations sergeant for the Story County Sheriff’s Office. “You had an Iowa State student, so you had ISU involved. [Then], you had it taking place to pick up in Ames… and then the body was dropped in the county.”

Investigators from all over the country worked on Sheila’s case. But the primary investigating agencies were the Story County Sheriff’s Office, Ames Police Department and the Iowa Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI) — now known as the Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation.

“You had three different agencies working on it all collecting their own stuff, and it was all separated for quite a while,” Rhoad said.

Today, the Story County Sheriff’s Office is the primary investigating agency and holds most of the evidence in Sheila’s case. Once it was determined that they would primarily investigate Sheila’s murder, the other agencies began to transfer the evidence. But there was one major piece of evidence missing: the pipe the murderer used to strangle her.

To this day, the pipe hasn’t been found.

Investigators’ biases also contributed to complications in Sheila’s case. Old profiles and forensic reports revealed that they used sexist and racist logic to analyze her case, according to Rhoad.

“You go back and read the FBI profile — it’s really, really, really bad [and] not good at all,” Rhoad said. “It’s sexist [and] it’s racist.”

Despite claiming to have no authority over local crimes, an agent from the FBI responded to a request from BCI for input on Sheila’s case.

“She does not appear to be an attractive girl, and, therefore, there does not appear to be any reason for someone becoming infatuated with her or having a great desire for her,” FBI agent Walter McLaughlin wrote in the letter. “She was just a victim of circumstance, her name happened to be on the right board to suit the killer’s purpose.”

Nancy Bowers, a historian and researcher who studied Sheila’s case, said the report was insensitive and had elements of victim-blaming language.

“That was pretty crude stuff, you know, blaming the victim,” Bowers said. “And of course, again, you have to look at the time frame, saying she wasn’t attractive, so therefore nobody wants to rape her — I mean, that’s just an atrocious comment to make.”

In his letter, McLaughlin questioned the postmortem report that claimed Sheila was not sexually assaulted.

“If sex of some intimate nature was not involved, it would have been unnecessary to remove the victim’s clothing,” he wrote.

While analyzing the murderer, McLaughlin assumed it was a young, white man because Black men “do not go in for this fancy-Dan stuff. They ordinarily rape, accompanied by brutality, but do not use sadistic refinements such as the pipe and nylon cord.”

Despite the FBI’s belief that the murderer was a white man, many people of color were brought in for questioning in Sheila’s death.

“One of the difficulties is that when people are thinking about a killer, they think, ‘Oh, this is a mouth-breathing, knuckle-dragging monster,’” Bowers said. “He had to stand out. Which is why the police went around and every Black person they found they interviewed and brought in because they’re ‘the others,’ they’re ‘the different,’ and that must be who did it.”

Investigators’ biases hindered the timeline of the case, Bowers speculated, but so did the influence of outside sources. Bowers said she believes then-Story County Attorney Charles Vanderbur’s political aspirations may have influenced his role in the investigation.

“I think he wanted to use this case to springboard into political ambition or political activities,” Bowers said in an email.

“Sheila was victimized twice, once by the killer and again by the county attorney, who misrepresented her and her life to the media who unknowingly reported the false information to the public.”

Vanderbur claimed that Sheila was a “student radical” and involved with drugs — both assertions were patently not true.

Vanderbur died in 1978, but the information he gave to the press had a lasting impact on the public.

“I still run into people who say, ‘Oh yeah, that was the girl who was dealing drugs and that they found out by Colo.’ Well, no, she wasn’t,” Bowers said. “It’s not fair to her because I think it caused there to be a lack of interest in pursuing the case and in finding the truth.”

Future of the investigation

According to Rhoad, solving Sheila’s murder hinges on improvements in DNA technology.

“Every lead has been absolutely exhausted. The only thing that is really left is if you could somehow get that piece of DNA,” Rhoad said.

The sheriff’s office retains a sample of DNA that was collected from the crime scene evidence. So far, analysis of the strands has not been fruitful.

“They got a mixture of two DNA, one a female and one a male,” Rhoad said. “But the chain is so broken and mixed together that they can’t put any kind of a profile together that would allow us to identify anybody.”

In recent years, several cold-case murders have been solved using new DNA technology. These prospects could allow investigators to connect existing forensic evidence to a suspect.

Law enforcement even has access to DNA samples from websites like Ancestry.com. When individuals send their DNA sample to be tested, the company creates a profile for the person. If a suspect has a profile on these websites, investigators can use that DNA sample to determine whether it matches DNA from the crime scene. Even samples from a relative can provide enough genetic material to create a match.

In 2009, the Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation established a cold case unit, hoping that DNA advancements would lead to breakthroughs in older cases. Sheila’s case was one of about 150 unsolved crimes under investigation. In 2011, before any breakthroughs were made in Sheila’s case, funding for the unit expired.

For now, the murder of Sheila Jean Collins remains unsolved. Her killer has walked free for more than 50 years.

“This is what always haunted you,” said former Iowa State student Joyce Durlam. “In the back of your mind there was always this thought — they haven’t caught the guy. He’s still out there.”

If you have any information about this case, please contact the Story County Sheriff’s Office at 515-382-6566.