Wine making in Iowa: a little-known, yet wildly successful industry

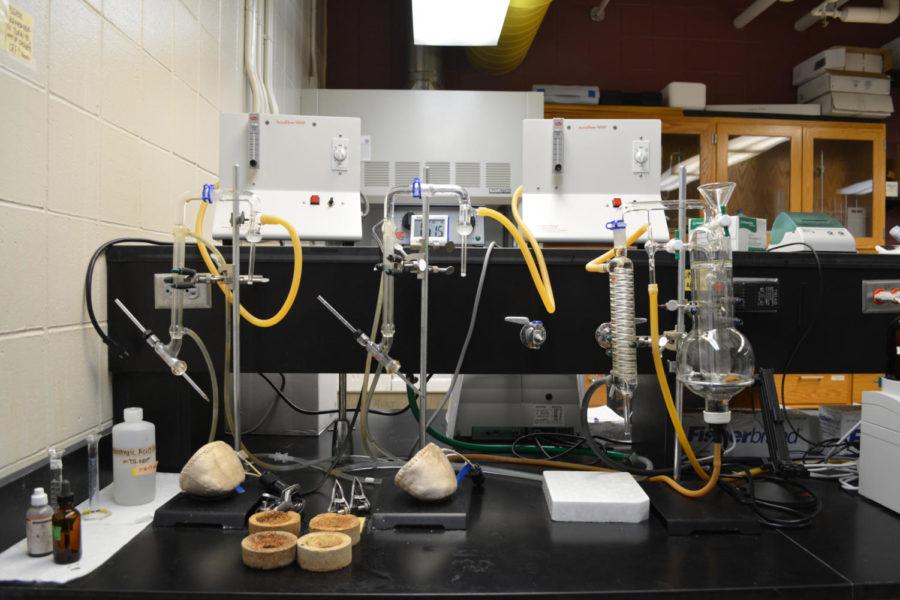

Katlyn Campbell/Iowa State Daily

Volatile acid stills sit in the Midwest Grape and Wine Industry Institute lab in the Food Science Building. This equipment is used for measuring volatile acidity and total sulfur dioxide.

February 19, 2017

It was a snowy February morning in 2000 when 125 people piled into the Odd Fellows Hall in Indianola, Iowa, for the first Winegrape meeting.

Michael White, field specialist in viticulture for Iowa State University Extension and Outreach and the Midwest Grape and Wine Industry Institute, looked around the room and knew it was the start of something big.

“The enthusiasm was there, the money was there, the intelligence was there — I knew this was going to go,” White said.

White was referring to the now highly successful wine industry in Iowa.

In the beginning

When Ron Mark, owner of Summerset Winery in Indianola, asked White in December 1999 whether Iowa State University Extension and Outreach could put together some grape-growing classes, growing wine grapes was not a priority for many.

White, then the Iowa agronomy crop specialist for Iowa State University Extension and Outreach, saw the potential — despite hesitation from Iowa State University — so he led the first Winegrape meeting.

At the time, only two Iowa wineries made wine out of grapes from their own vineyards, but he saw undeniable interest and a need for more grape growing in the state.

For the next three years, Mark and White held monthly meetings at Summerset Winery, consistently drawing about 75 to 125 people interested in the industry.

In 2007, Iowa State University told White to choose between agronomy and wine.

White chose wine and has never looked back.

He reminisces about the participants’ enthusiasm and the fun they had together finding their way in the early days of the industry in Iowa.

“At first, it was the “blind leading the blind,” he said.

People with aspirations — hobby wine makers, people who had traveled abroad and people who viewed wine as a part of the culture — were amazed that they could grow grapes in their home state.

“At the beginning it was fun; everybody was having a great time,” White said. “We’d bring in speakers from all different states to come and talk to us. So it was a growing industry, and everybody worked close together. From 2000 to 2010 or so that was the way it was, a growing industry.”

Reaching maturity

This rapid growth eased in 2010, and the industry has stayed relatively stable since then, White said.

“In 2010, we kind of hit the growth curve up at about 100 wineries and 425 vineyards covering 1,200 acres, and then we started [to plateau],” White said. “The wineries started staying the same; for 6 years we’ve been bouncing up and down from 100 wineries.”

The vineyards have matured and condensed since that time, with 270 vineyards now covering the same 1,200 acres in the state.

“We’re in a mature market now,” White said.

Along with the second generation of grape growers and winemakers has come maturity.

“The cowboy area of any industry as it grows is kind of crazy and wild. They don’t pay attention to all the data and curves, the business analytics and all that, but then as the second generation comes in, the accountants come in, and you’re doing proper business practices.

“The fun starts to go away; it becomes a business,” White said. “It’s not as fun as it used to be, but we’re still having a good time.”

Midwest Grape and Wine Industry Institute

To support the growing wine industry in Iowa, Iowa State University started the The Midwest Grape and Wine Industry Institute.

It was approved by the Iowa Board of Regents in 2006 and is the only such institute in Iowa, according to the ISU Extension and Outreach website.

The staff at the institute conducts research on grape growing and winemaking, hosts events and workshops to help teach winemakers and viticulturists how to better their practices and partners with community colleges.

White is among the staff, with a clientele of more than 2,000 vineyards and wineries across the Midwest.

The staff also includes a team of various other members, including two part-time undergraduate lab assistants.

Maureen Moroney, research associate at the institute, graduated from Iowa State and joined the team in February 2016 after working with production wineries in California since 2008.

“I loved [working in production], but one of the drawbacks is that when you’re winemaking, you run into all these questions that in a production setting, you don’t really have the freedom to pursue the way that you might like to,” Moroney said. “Ultimately, you need to be focusing on making the best product, not chasing after all these other questions.”

This desire to research was a main reason Moroney returned to her alma mater.

Moroney’s main responsibility is working in the service lab that analyzes samples sent in by industry members.

“If they don’t have the capability to do their analysis on site, then they send it to us and we do it for them for a fee,” Moroney said.

She also is available for industry members to call with questions or concerns. She does site visits, is involved with workshops and trainings, and participates in the research.

Somchai Rice, assistant scientist for the institute, also researches.

“In the lab, we have some HPLC instruments, some mass spectrometry instruments, an eNOS, all of that kind of more state-of-the-art type instruments that a normal winery or vineyard wouldn’t have access to, or have anyone trained to use,” Rice said.

Snus Hill Winery takes advantage of the institute’s services.

“We send samples prior to bottling,” said Chris Hundall, co-owner and general manager of Snus Hill Winery. “They have the ability to analyze our wine a lot more in-depth than what we can do in our laboratory. We can do some of the same testing, but when we send it to them it’s a lot more accurate and a lot more involved.”

This research is important for the institute and the wine industry in Iowa because the Vitis vinifera grapes, the grapes typically found in warmer climates such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir, have been researched extensively, whereas the cold-climate grapes are less known, Rice said.

“We know [cold-climate grapes will] grow in the Iowa climate, but we don’t really know their aroma profile — how winemakers should be using them,” Rice said.

This research, paired with the outreach programs, has helped local wineries thrive and fostered the industry’s rapid growth.

The industry today

About 105 wineries in the state together sell about 311,000 gallons of wine per year, according to the Alcohol Beverages Division.

Of 105 wineries, the top 23 account for 80 percent of the industry in the state. These top 23 wineries are making money on wine, as well as other entertainment revenue sources, while the other 83 wineries are not making money on the wine itself, White said.

“It’s part of the mix, but they can’t live on it. They’re making money on the events … weddings, meetings, etc.,” White said. “It’s [an industry that is] highly associated with tourism.

A 2012 economic impact study done by Frank, Rimerman + Co LLP, an accounting company based in California, showed that every $1 spent in wine sales in Iowa generated a $28 economic impact on the state.

Why is the economic impact so high?

“Because the wine sales in Iowa are all about tourism,” White said. “It’s all about tourism — events, food, gas, lodging, gifts, etc. The wine is the seed. If you have good seed, you can bring all those things in that package together.”

Snus Hill Winery, one of those top 20, takes advantage of the entertainment side of the industry as well.

“In my opinion, the wine consumption in Iowa is not large enough to operate on just selling wine only,” Hundall said. “In order for us to get people out here to get them to buy our wines, we offer live music events, Christmas parties, things like that.

“So not only are we a wine producer, we’re also an event venue, too. That just helps turn the wheels, bring in that additional income for overhead costs.”

What makes Iowan wine unique

One major difference between Iowa wine and wine grown in warmer states, such as California, is the type of grapes.

“The difference in the grapes in Iowa is that in the early 1990s, there started to be a movement called Cold Climate Viticulture, where we started looking at American grape varieties and French grape varieties which could create hybrids that could withstand the climate,” White said.

The University of Minnesota and Cornell University were key players and started releasing wine grape hybrids soon after.

This movement really took off in 2000, with Iowa leading the industry with the fastest growth.

“In Iowa, we have about 40 different grapes that we’re growing, about 10 of which are native and 30 of which are different hybrids that we can select. We have new hybrids coming out about every two to three years,” White said.

To put the growth into perspective, White said that Cold Climate Viticulture is growing faster than the California wine industry did in the 1970s.

“Not only is it growing in Iowa, but it is also growing across the northern 20 percent of the United States … into Canada and northern Europe, as well,” White said. “It’s just growing dramatically. It’s all about cold-climate viticulture [right now].”

While California still produces a majority of the wine in the United States, with about 85 percent of all wine production, White said it is not a quality issue.

“You can take Iowa wines and go to California, to the best competitions, and you’ll get gold medals,” White said.

But Iowa winemakers have to work with acid in these cold-climate grapes, Moroney said.

One popular option for dropping the acid level to make a more balanced wine is to add sugar.

Semi-sweet and sweet wines are extremely popular in the industry, with roughly 70 percent of American wine drinkers having sweet palates. But they present the issues of stability, microbial spoilage and re-fermentation.

“Those are your choices, you can either make a dry wine that is stable but that is way too tart, or you can make a sweet wine that if you don’t do a perfect job with sanitation and filtration, it’s going to re-ferment and spoil,” Moroney said.

Where will the industry go in the future?

“From a consumer prospective, one of the challenges here is that even in Iowa nobody has heard about Iowan wines,” Moroney said. “We’re just not considered a winemaking region, and part of that is because it’s so young.”

This problem is what Moroney thinks will change in the near future.

“I would love to see that perception change,” Moroney said. “I would love for people to see winemaking viable career, and a profitable career, and be taking it really seriously and devoting their lives to it and be making some fantastic wines.

“We have some young winemakers that are doing that, who are taking it very seriously and have come to every single one of our workshops, and are doing absolutely everything they can to do the best job they can.”

White agreed, saying that the wine industry in Iowa has the potential to improve with the passion of the next generation.

“We can do anything,” he said.