Rare Disease Day: ‘Different is different, it’s not bad’

February 27, 2017

Before attending Iowa State, Jeilah Seely, junior in advertising, attended East High School in Des Moines. At 15, she began enrolling at Des Moines Area Community College (DMACC) and Central College for summer classes.

As the end of her high school career drew near, members of the community Seely lived in began to notice changes that raised enough concern for them to urge Seely’s family to take her to see a doctor. This was especially the case for her professors and academic advisers.

“My handwriting was getting crappy, the quality of my work was lower, I wasn’t getting through my books as fast and I was getting really confused,” Seely said. “I was looking tired in class. I wasn’t my normal peppy self.”

Seely has worn glasses since she was seven years old. Her family had taken her to doctor’s visits on several occasion with concerns about her vision.

“The doctors never thought anything of it, so we didn’t think anything of it,” Seely said. “My mom knew I was clumsy and got sick a lot. [Vomitting] is part of my disorder.”

At age 18, with the help of two Iowa State alumni, Seely was diagnosed with an accommodative dysfunction. This dysfunction has resulted in Seely developing an eye disorder. Seely said that whenever people ask, she usually just tells them that she is blind.

Accommodative dysfunction is a rare illness that causes symptoms to occur when individuals bearing the illness place strain on their eyes. With contacts or glasses Seely can see 20/20, but her disorder presents challenges that go beyond sight.

“If it’s too sunny or I have to keep going [indoors and outdoors] or if someone hands me something with really small print, I get sick, my head hurts and then my vision starts to go away,” Seely said.

Iowa State’s Student Disability services have provided Seely with adequate accommodation for her academic success. Seely’s disorder requires font sizes, extra time on exams and surveillance to ensure that she doesn’t lose consciousness during class.

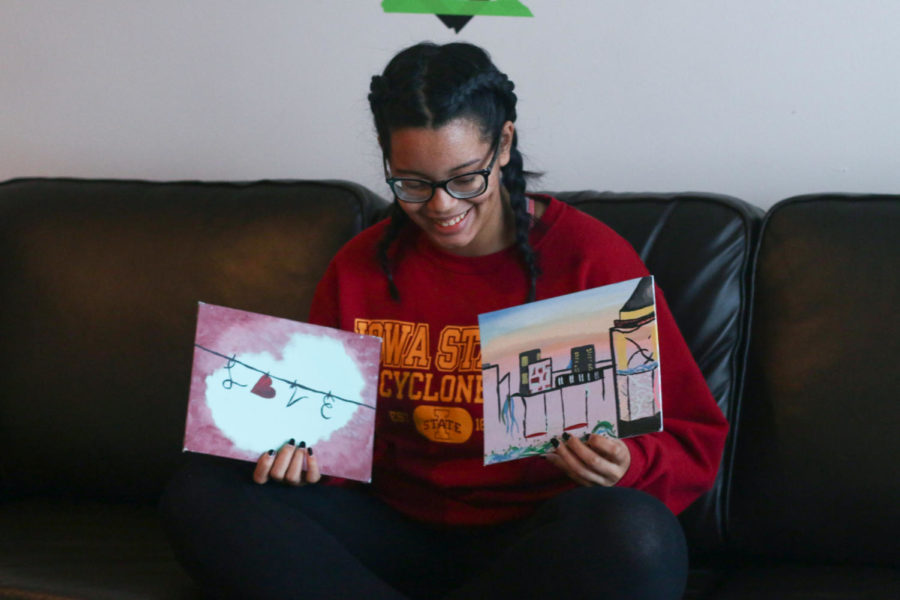

When not in class, Seely can be found painting in her apartment. She hopes to manifest this hobby into a small business.

“I downplay what it is that I have because I’m just not the victim type [of] person,” Seely said. “What I can’t downplay are what my accommodations have done for me and how much they’ve helped me get where I am.”

Seely urged other students to own their disabilities. She said that she can relate to students who are afraid to be open about their illness.

“Don’t let people limit you,” Seely said. “There’s a lack of understanding and information, so people don’t realize they’re being difficult. Just because you don’t see [the disease], doesn’t mean it’s not there.”

Heather Reimers, senior in apparel merchandising and design, said that the lack of misunderstanding spans beyond that of students, but members of the university’s administration as well.

Reimers was born with osteogenesis imperfecta, a rare genetic disorder characterized by bones that break easily, often from little or no apparent cause.

The number of people affected with OI in the United States is unknown. The best estimate suggests a minimum of 20,000 and possibly as many as 50,000 people affected, according to oif.org.

As a result of the disease, Reimers has been confined to a wheelchair her whole life thus far.

“I’ve had to fight a lot of battles within my own major of getting accommodations,” Reimers said. “I’ve received a lot of negative reminders that [I] probably can’t do [things] like everyone else, but I can always find different ways to do things.”

Born and raised in Des Moines, Reimers had always housed a love for fashion. She realized during her senior year in high school that she wanted to do something in the realm of creativity as a career choice. Reimers said that Iowa State’s fashion program drew her to the campus.

Reimers is also a member of Gamma Rho Lambda National Sorority, a multicultural social sorority for women, trans-women, trans-men and non-binary students. She was a founding member of Iowa State’s chapter, having joined in 2014.

Reimers had to learn adapt and think outside of the box growing up. She said that her biggest challenges yet have not been physical, but social.

“Being treated and looked at like I was five years old [was a challenge],” Reimers said. “Growing up, people would talk down to me a lot. Getting people to look past the wheelchair and look at the mind [has always been a challenge].”

Though the students in her department have been accepting of Reimers and her condition, she said that most of her problems have come from the administrative level of her college.

“I had some moments where I thought I should give up and switch majors,” Reimers said, “but I guess my mentality that I’ve had since I was a kid, that ‘I’m going to prove you wrong’ attitude, has pushed me through.”

Though she is confined to a wheelchair, Reimers requires no assistance to complete essential tasks. Reimers has aspirations of working for her dream company, Patagonia, post graduation.

“[Disability] is a taboo subject to talk about,” said Laura Wiederholt, senior in biology. “People are afraid of offending us. People tend to feel really sorry for us and don’t want to saying anything to offend us.”

Wiederholt is the president of Iowa State’s Alliance for Disability Awareness (ADA). She explained that people are afraid of approaching something different, but it is more upsetting to the disabled community at Iowa State when people do not communicate them. She added that students with rare diseases have issues connecting with others, so students are a lot less likely to empathize with them.

“[The ADA also] focuses on showing [the Iowa State community] that [disabled individuals] are just like everyone else and removing the [social] stigma placed on disabilities,” Weiderholt said.

Brittni Wendling, junior in public relations, added that the topic of disability on campus is ignored and overlooked.

“No one wants to talk about the issues that come with [disability],” Wendling said. “Ignorance is a big issue. No one wants to understand what someone else is going through.”

Wendling was born with Larsen syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects the bones in her body. All of her joints are dislocated, and she doesn’t have knees, rendering her unable to bend her legs.

Wendling was noticeably ill on the day of her birth. She was flown to a hospital at the University of Iowa, where she would undergo an operation. Wendling said that it took a doctor from London to diagnose her illness.

Upon arriving at Iowa State, Wendling said she wanted to just blend in.

“I didn’t want to stand out and address my disability,” Wendling said. “[My condition] might make things harder, but adaptation is a beautiful thing.”

Wendling said that every day starts with a measurement of pain.

“Usually I can tell right away if it’s going to be a good body day or a bad body day,” Wendling said.

Wendling suffers from chronic pain brought on by her condition. Extra bodily stiffness and pain usually signifies the start to a rough day. Wendling plans her days based on this gauge, but it typically doesn’t hinder her ability to do the things she enjoys, which include swimming and streaming her favorite shows on Netflix.

Wendling is not a student worker in the office of the vice president for diversity and inclusion. She plans to pursue a career in advocacy for disabled persons post-graduation.

“Different is different; it’s not bad,” Wendling said. “The more we try to normalize disability, the easier it will be on people with or without disabilities.”