Doctoral student strives to aid low-vision students in STEM education

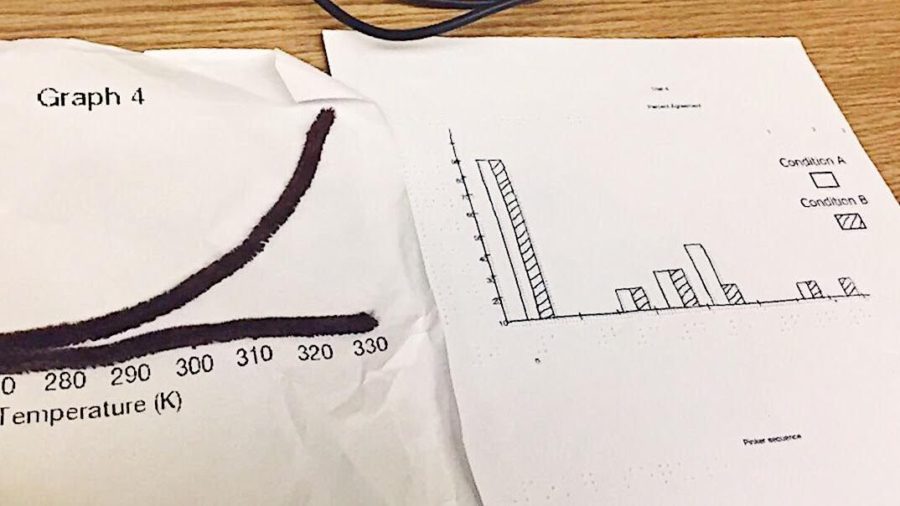

A graph used in high school algebra classes created with pipe cleaners (left) was created by Ashley Nashleanas as a more cost effective way to represent what could have been done by a Braille embosser (right).

February 27, 2017

Although she has never been able to see graphs and figures in her math and science classes, Ashley Nashleanas works with them every day for her studies.

Nashleanas, graduate student in education, has been blind her whole life. Nevertheless, her disability has not stopped her from becoming a Paralympic swimmer, completing her bachelor’s degree in chemistry at the University of Notre Dame and getting a master’s degree in chemistry from Iowa State.

Now, Nashleanas is doing research to help other students like herself be able to use graphics in a more accessible way.

Nashleanas grew up in Hinton, a small town in northwest Iowa. She was always interested in the sciences, even as a young child. Learning how and why things worked fascinated her.

As Nashleanas started to take higher level science courses in high school, such as physics and chemistry, math became another strong interest of hers. But something was missing.

“Accessibility was hard,” Nashleanas said. “I had textbooks in Braille, but they wouldn’t include the graphs that were in the original text. So some of the information was missing, which made it more difficult to understand what I was given.”

Nashleanas said she got lucky. In high school, a small network of people was able to look out and help make the best possible learning environment for her.

“I talked to my teachers about how we could construct images and fill the gaps,” Nashleanas said. “Other people I’ve met, either during my undergrad or getting my master’s, were in less fortunate situations. A lot don’t have that support.”

While studying chemistry as an undergrad, Nashleanas made friends with other students who were blind or had vision impairments. Many of these peers had a harder time filling the missing gaps in their education while in high school. She said these experiences led her to want to help people know what options they have to work with.

Nashleanas’ current research deals with creating ways to make graphics and images used in high school algebra courses accessible to students with low vision. The studies deal with not only giving students with abnormal vision options to “view” images but also how to create graphics themselves.

“Algebra is what can start or stop motivation,” Nashleanas said. “In elementary and middle school, they usually don’t use many graphs, and in college, students already have some sort of idea in their minds of what they can accomplish. … High school is sort of that sweet spot.”

Some technology is already available for low-vision students to use in STEM courses, such as technographics, but it can be costly and take a fair amount of time to create images.

Nashleanas and her supervising professors, Gary Phye and Anne Foegen, want to create options for students and teachers to use on the fly when funds and time are unavailable.

Nashleanas gave an example of a graph created using a Braille embosser that creates bumps on paper that a person with low vision can feel to get an idea of an image or to read text. The creation is effective for the user, but when asked if this was a more expensive option to use, Nashleanas laughed.

“Oh yeah,” she said. “These things can cost thousands of dollars.”

Nashleanas gave another example of a more cost- and time-effective option of a graph. Pipe cleaners were glued to a sheet of paper to form the shape of the graph, with Braille only used on the axis to show what numbers were represented.

“With this one, well, I mean, pipe cleaners will cost you nothing,” she said.

Other options Nashleanas and her professors have been using are things such as Play-Doh to create physical 3-D shapes for blind people to feel and measure out for geometry lessons. No two cases of blindness are completely the same, so the team tries to cater to the needs of the individual student or school they are working with.

Nashleanas, Phye and Foegen have been working with high schoolers and teachers across the country for their research. A lot of networking has gone into finding students and schools to participate.

Nashleanas’ academic adviser had connections to the Iowa Braille School, which in turn was able to put the team in contact with teachers and schools throughout the United States.

Nashleanas said the teachers they have collaborated with have been accepting of their ideas, but they have been met with some unawareness. She said some people take a bit more time to get started, but they have never been reluctant to become more aware of the needs of blind students.

“I think it’s unfortunate to be reluctant with those who beg for accommodations,” Nashleanas said. “They’re shutting themselves out from learning with others.”

Despite positive numbers and data in their research, Nashleanas believes that asking for complete awareness for the needs of low-vision students in schools is a tall order. She said blindness is a rarity, and it would be a long process to assess the needs of different people.

Nevertheless, finding success individually is not as much of a tall order for Nashleanas. She said that although she thinks the playing field for STEM students is initially uneven, when people with abnormal vision find their own academic support group, there is more equality as they begin to discover what works for them.

“I didn’t know what I needed at first, so I looked at blogs and talked to people, teachers,” Nashleanas said. “But when you do know what you need, and have people working with you, it gets easier.”