Snyder: Ernst should know better

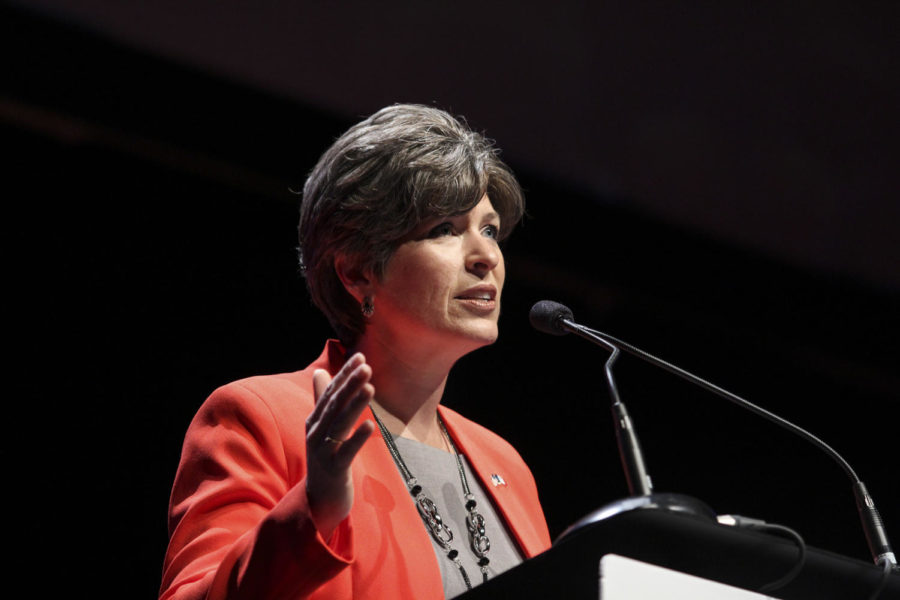

Kelby Wingert/Iowa State Daily

U.S. Senate candidate Joni Ernst spoke at the 2014 Family Leadership Summit on Aug. 9 at Stephens Auditorium.

January 23, 2015

Following the State of the Union address, Americans have a clear view of the next two years in national politics. President Obama made no attempt to hide his belief that the policy adjustments and social reform he has set in motion will work to the benefit of the American public.

To that effect, Obama made it clear that he has the veto pen ready should Congress attempt to push any counter-legislation through his office during the next two years.

As entertaining as Obama’s address was on its own — and I really thought it was — thanks in no small way to what was perhaps the most well executed comebacks of all time by Obama, the President’s address was not even the main event for many Iowans that tuned in.

Freshman Senator Joni Ernst was given the privilege of offering the official Republican response to the State of the Union. Ernst’s selection speaks to the massive popularity she gained among conservatives during last November’s midterm elections.

Those of us who may not have voted for Ernst, however, sat in terror waiting for the inevitable moment of embarrassment to come when Ernst reflected on her upraising in Red Oak, Iowa.

Ernst did not disappoint. Less than two minutes into the speech, the audience transported back to small-town Iowa and now infamous Hardee’s biscuit line. However, the Ernst nostalgia generator also brought a new treat for Iowans to cringe over.

“… On rainy school days, my mom would slip plastic bread bags over them to keep them dry. But I was never embarrassed because the school bus would be filled with rows and rows of young Iowans with bread bags slipped over their feet.”

This may very well have been a generational experience — or a shoe deficit matched with a bread surplus — but Ernst’s message quickly became cannon fodder for the national news outlets, setting the image of our state back even further than the deep-fried Twinkie.

Even more disconcerting is the fact that Ernst pointed out what amounted to the community-wide poverty of her entire hometown and did it with a smile on her face. Poverty is not a subject to hold up as the authentic American experience and I’m willing to bet that none of those other bus riders became U.S. Senators.

The poverty that Ernst recalls so fondly pulls hard on the dreams and aspirations of countless masses of Americans whose struggle remains faceless because even though Ernst could be their champion, it seems she will staunchly remain an enemy.

Ernst may believe that she typifies the “American dream” of rising from poverty to assert her presence in the company of the politicians who ignored her town, but Ernst’s experience is more of what I would consider the American tragedy.

The tragedy is that the children riding that bus — were they indeed living in poverty — are most likely still stuck in the ever-present quicksand that is economic inequality. In 2013, CNN Money reported that 70 percent of people born into poverty would stay there. Only 4 percent will become high earners like Ernst.

Perhaps some optimism can be found in the fact that those numbers mean that just over one-fourth of those children might find their way into the middle class.

However, the report also details that more than half of that fourth were college graduates, and in a country where a college education has become increasingly unattainable for low-income students, the odds of upward economic mobility are constantly shrinking.

There is a second tragedy in Ernst’s experience. She is finally in a position to help those who grew up like her — maybe even people still living in Red Oak — but because Ernst is of that slimmest minority of people who have risen above their initial tax bracket she feels justified in enacting policies that encouraged the impoverished to keep working and live without the assistance of government programs.

Imagine if — as President Obama has recently proposed — community college was subsidized so that those with the highest level of need could invest their money elsewhere. Rather than saving money from her fast food job to invest in her education, she could have been funneling that money into her family’s earnings, improving all of their lives.

Imagine if minimum wage in Iowa had been increased at the same time. Ernst might have been able to set aside some money for a second pair of shoes.