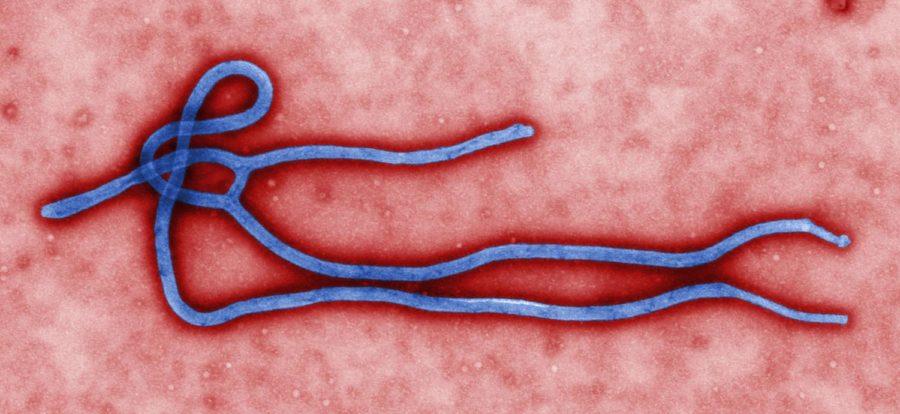

Ward: Ebola, the fear of two continents

NewLink Genetics, an Ames company housed in the Iowa State Research Park, has recently signed a $50 million deal with Merck & Co., Inc. to expedite the development of NewLink’s potential vaccine for the Ebola virus.

October 6, 2014

We all know the drill when we go to the doctor. A majority of the time is spent in the waiting room and the time with the doctor is fleeting, mostly due to the fact that they have to see lots of people with varying degrees of sickness. Because these doctors have so many people to take care of in a day, they have a tendency to take the fastest route to get you out of the door and move onto the next patient. That route is generally a bunch of medications.

The average number of prescriptions filled by pharmacies in the United States and given to people between the ages of 19-64 is 12.3 per year, according to a 2013 study done by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

My guess is that a nice chunk of those prescriptions were unnecessary. However, we as a society have been brought up to trust the word of the person who went to medical school for a ridiculous number of years in order to tell us what is wrong with us. Why would we question them?

Surely that was the exact same logic scrolling through Thomas Duncan’s mind when doctors at the Dallas-based Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital sent him home with a prescription for antibiotics after he returned from working with Ebola patients in Liberia, and he wasn’t feeling so great.

On Aug. 1, a protocol was issued by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention saying that anyone who had recently returned from Liberia and came to a hospital complaining of medical ailments was to be put in isolation and tested for the Ebola virus immediately. Not only did the hospital fail to follow federal protocol, they failed to even attempt to see if anything was truly wrong with Duncan.

Four days after Duncan’s initial hospital visit, on Sept. 29, he returned to the hospital via an ambulance and this time protocol was followed. He was diagnosed with the first case of the Ebola virus on American soil. A statement was released by one of the hospital’s administrators saying that the news of Duncan’s recent trip to Liberia had been overlooked.

Isn’t it the job of doctors to carefully notice and document everything a patient tells them? Whoever “overlooked” Duncan’s Liberian travels has some serious explaining to do and should probably reconsider their career choice.

David Lakey, Texas health commissioner, said during a press conference on Oct. 1 that, “This is not West Africa,” meaning that the United States has the resources to fight this disease. Glad to see you’re up on your geography, commissioner, but simply being located in a country more equipped to fight this disease than West Africa means nothing if the people we entrust with our lives cannot successfully complete the tasks of health care.

This whole ordeal sounds like the plot out of a Hollywood horror flick, but this is real life. It has caused people across the country to become a little more leery of their diagnosis during the start of cold and flu season and has resulted in a trend on Twitter of people asking if they have Ebola. But even beyond what could potentially turn into mass hysteria, the situation has sparked a question of why the hospital didn’t assume the worst in the first place, given the medical industry’s history for overmedication?

Was it due to the fact that they didn’t want to be “better safe than sorry,” put Duncan in isolation just in case but potentially deal with the aftermath of being wrong or was it really due to human error? Neither option is all that stellar, and it really makes one wonder how much medical care is really in the best interest of the patient or the reputation of the medical facility.

Had the hospital taken precautionary measures during his first visit, it would have also prevented the mass isolation of every person — 80 people in total — that Duncan came into physical contact with either directly or indirectly over the four day period between his initial visit and his admission to the hospital. Among those on a 21 day watch are the four members of his host family and five elementary-aged children who have since been pulled from school. Keep in mind, however, that they were only pulled from school after Duncan was hospitalized, so they went to school potentially infected with the disease. This news spread like wildfire and now parents are pulling other children out of school who didn’t even come in direct contact with Duncan but who could have had contact with the initial five kids. Even individuals who never came in contact with anyone close to Duncan are walking around wearing medical masks to try and protect themselves.

Because this hospital decided to take a shortcut and ignore policy and common sense they have disrupted not only a state but have also caused fear to course through the entire country unnecessarily. Protocols exist for a reason, but because Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital turned a blind eye to these procedures they now have to live with the fact that they are responsible for putting a man’s life carelessly on the line and causing Americans to think that an Ebola outbreak is on the horizon.