Kyven and Willie: The trials and tribulations of the Gadson men

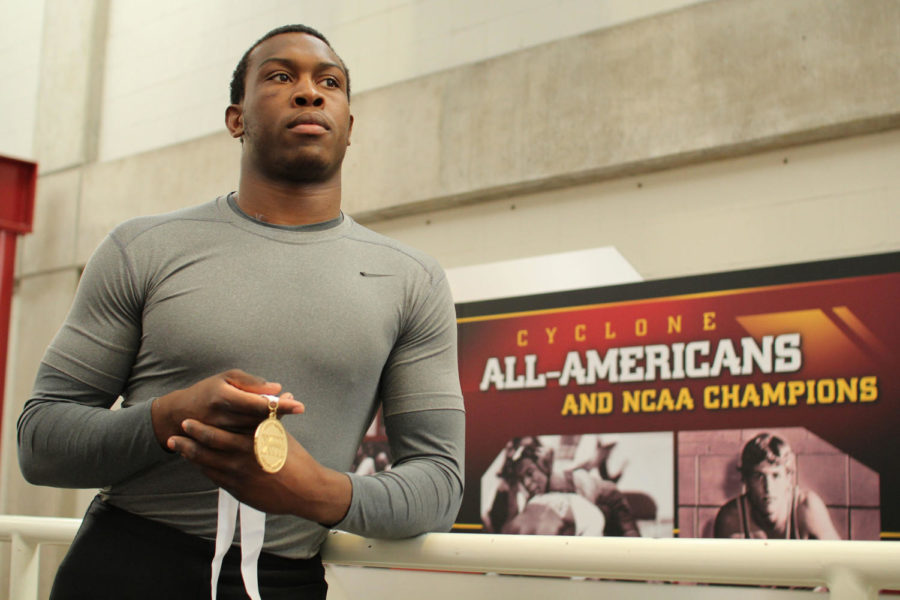

Miranda Cantrell/Iowa State Daily

Redshirt junior Kyven Gadson finished sixth in the 2013 NCAA tournament. He is currently ranked No.1 in the 197-pound weight class. He will wrestle in the Big 12 Championships on March 8.

March 6, 2014

In an empty hallway of Wells Fargo Arena at the 2009 Iowa High School State Wrestling Tournament, Kyven Gadson stood in front of his coach, desperate and dejected. He had just lost in the finals and as he looked his coach in the eye, he said, “I’ll do whatever you tell me to as long as this does not ever happen to me again.’”

Kyven’s coach and father, Willie Gadson, accepted.

***

Willie had a father who taught him the enduring, painful lessons and trials of manhood at a young age. Willie’s father showed him what not to become.

One of four children born to Bernice and William Gadson, Willie spent the first 10 years of his life — 1953-63 — in South Carolina, working in the cotton fields.

The hard-nosed work ethic that would define Willie later in life was forged underneath the unforgiving and unrelenting South Carolina sun as he walked through row after row of cotton, harvesting the sinewy lint from boll after boll, day after day. Working hard became the norm in Willie’s young life, and nothing came easily.

His life at home was no exception.

Willie’s father was an alcoholic, and according to Willie’s wife, Denita Gadson, there was, “quite a bit of domestic abuse.” In 1963, Bernice had had enough.

She took her children, left the cotton fields and abuse behind and moved to New York. It was in Huntington, N.Y., that Willie Gadson met Lou Giani, the man that changed the course of his life.

Giani, a wrestler at the 1960 Rome Olympic Games, took Willie and his brother, Charles, under his wing. Willie was out of the South, but what he had learned from his time in South Carolina did not leave him.

With nothing but his work ethic and the tutelage of Coach Giani, Willie began to flourish as a wrestler; Denita says Giani and wrestling provided something more for Willie and his brother.

“Coaches complete the gap,” Denita said. “They do a lot more than just coach. When Coach Giani came to Huntington and Willie started with wrestling, that’s really when his life started to turn around — and up to that point, he was kind of lost in the sense that he didn’t have direction.

“He got into a lot of things, and it’s amazing that with the kind of things that inner city kids get into, it was just amazing that he came out of New York and that he came out alive. He came out without ever having gone to jail.”

Willie left Huntington in 1972 to enroll in Nassau Community College in Nassau, N.Y., where he compiled a 45-0 record in two years en route to two national titles at the junior college level.

After finishing his two years at Nassau, Willie left for another region of the United States. He found a home and a place to wrestle at Iowa State, under the trained and watchful eye of Harold Nichols.

Just as with his previous coaches, Willie thrived under Nichols: He won two Big Eight titles, took third place at the 177-pound weight class at the 1975 NCAA championships, took sixth in 1976 and captured two Midlands Championship wins. It was not until after his days as a wrestler concluded that Willie found his niche and took on his most known role: Coach Gadson.

As an assistant coach for the Cyclones from 1979-82, Willie worked with Nate Carr, one of three wrestlers in ISU history to win three national titles.

In 1992, Willie landed a job as the head coach at Eastern Michigan University. While at Eastern Michigan, Willie led the 1995-96 team to one of the program’s best seasons by winning its first ever Mid-American Conference Championship and being named Middle American Conference’s Coach of the Year.

No matter where Willie went, he seemed to get the best out of his wrestlers.

“Willie saw, because of his own upbringing and family dynamic, that he was going to and provided for those kids a sense of stability and consistency,” Denita said. “He was no-nonsense and didn’t like foolishness, but he had a way about him that kids loved because they knew that he was going to be there for him if they wanted him there, even if they weren’t wrestlers.”

When Willie left Eastern Michigan in 1997, he became an assistant coach at Iowa City High School. He became head coach of the Waterloo East High School wrestling team in 2004, where he would mentor his star pupil: his son.

***

At a Hawkeye Kids Club wrestling practice in Iowa City in the early 1990s, as hoards of children — with daydreams of wrestling for the University of Iowa and the legendary Dan Gable — eagerly threw on their replica Hawkeye singlets and took to the mat like the legends of Hawkeye folklore, Kyven Gadson was focused on fashion.

“I would never wear the singlet,” Kyven said. “It’s one thing I would not do. They’d give you a replica Iowa singlet, and I was one of the few that refused to wear it.”

While Willie never pushed his son onto the mat, Kyven was certainly immersed in the sport from a young age, and the two formed a bond that made them almost inseparable. As a young wrestler, Kyven and Willie spent countless hours in the car, listening to their favorite oldies songs on their way to tournaments.

Growing up in Iowa City, Kyven was exposed to wrestling at all turns, whether it was watching his brother, Jared, wrestle in high school or tagging along with Willie to Carver-Hawkeye Arena to watch Iowa wrestlers.

At home, of course, impromptu wrestling matches were the norm. While the mat in the basement did not get much use, the carpet upstairs proved to be an ample substitute when the boys felt inclined to have a go.

As Kyven grew and the rug burns from the carpet faded, he began to distinguish the two sides of Willie, but sometimes Coach Gadson could make an appearance at home.

“As a kid, it was tough to break up the two into having ‘Coach Gadson’ and a dad and we had some talks about that,” Kyven said. “But just as a dad, I always felt like he was a general-type guy, but now looking back on it, he was just someone who really cared about his family and doing what it takes to keep it going down the right path.”

Hard work and doing things right are intangibles that Willie honed in his children at a young age, and dishes were one thing that General Gadson liked done right.

Kyven recalled one night when he and his sister were washing the family’s dishes: Plate by plate, glass by glass, they washed and dried the dishes before putting them back in the cupboard.

Willie had always threatened that if he found a spot on his dishes that he would make Kyven and his sister wash every dish in the house. Every dish.

A week later, Willie found a spot on a plate. General Gadson proceeded to remove every dish in the house, and Kyven and his sister cleaned each one of them.

“Stuff like that — that you don’t really understand as a kid, that once you get older and start maturing — it just all starts to come together and make sense,” Kyven said. “You might not know the reason for what he was doing, but there was always a reason.”

Willie’s lessons were not always clear, and Kyven’s ears were not always open. In his sophomore year of high school at the state wrestling finals, however, Kyven opened his ears.

Under the lights of Wells Fargo Arena, on possibly the biggest stage in Iowa high school sports, Kyven was in the finals for the first time in his career. He faced a grappler from Iowa City West named Derek St. John, Iowa’s current reigning national champion at 157 pounds. The match did not go Kyven’s way, and he was beat by major decision.

As St. John stood in the center of the mat and had his hand raised under the lights, staring into the crowd and taking in the moment that Kyven had dreamed of since he was a boy, the dejected Kyven found himself in a back hallway, face-to-face with his father.

“I decided to listen at that point,” Kyven said. “I told my dad in the back, ‘I’ll do whatever you tell me to as long as this does not ever happen to me again.’”

After that moment in the back of Wells Fargo Arena when Kyven opened himself to Willie as his high school career was wrapping up, Kyven finished his final two seasons at Waterloo East undefeated and as a two-time state champion.

At the culmination of his high school career, there wasn’t much discussion as to where Kyven was going to wrestle collegiately. The same boy who had once refused to don a black and gold singlet was bound for Ames, following the footsteps of his father.

In 2011, Kyven made his Cyclone debut at Hilton Coliseum against Oklahoma after redshirting as a freshman. It would be his first and last match for more than a year.

Kyven injured his shoulder during the match and had shoulder surgery in December 2011. It was also around this time that Willie was making strides to improve his own health.

Still at the helm of the Waterloo East wrestling program, Willie had decided he needed to drop some weight and get back into shape. While Willie was successful in his diet and workout plan, he noticed something out of the ordinary.

Wrestlers are often very in tune with their bodies and have an understanding of how the weight loss should go and how they should feel during the process. Willie noticed he was losing weight more rapidly than he should, and his weight and strength continued to drop even after reaching his target weight.

Willie went to a physician and got his health evaluated, then he went to several more.

The Gadson family got the final test results back and in March 2012, Willie was diagnosed with stage 4 lung and bone cancer.

***

Seven months later, a physically overweight and mentally overworked Kyven walked into the office of Kevin Jackson, Iowa State’s head wrestling coach, and sat down. He was done.

The sport he grew up around, the sport that he and Willie had bonded over his whole life was no longer fun; rather, it was now just part of the routine.

“Even at the beginning of the season, I wanted to quit,” Kyven said. “I walked into coach Jackson’s office and said, ‘I’m not doing this anymore, this isn’t fun anymore, so what’s the point? [Willie and I] set up goals for me and now he’s not here to watch me, so what’s the point?’”

Jackson listened to Kyven, who was not only struggling mentally but also physically.

“He was coming off a bunch of injuries [as well] and just wasn’t having success on the mat, and it wasn’t any fun. And if something isn’t fun, with as hard as wrestling is, it makes you not want to do it,” Jackson said. “We sat down and had that conversation, and luckily, he decided to stay with us.”

The 197-pounder ran through nine opponents before losing his first match during a season in which he would only lose twice before the NCAA Championships.

Throughout the season, Kyven was kept relatively in the dark as to the status of Willie’s health, per his father’s wishes. With every phone call, Willie would tell Kyven it was all OK, never giving the slightest hint that it was not.

Kyven’s career was just getting started in Ames, but Willie’s health was deteriorating back home. Just before the Big 12 tournament, Willie was at his worst.

“So the whole time during wrestling season, I didn’t know a whole lot, so there wasn’t a big worry,” Kyven said. “Dad’s going to do his best to fight this.”

The week before the Big 12 tournament in Stillwater, Okla., Kyven went with his family to the hospital and learned that Willie was nearing the end of his fight. The cancer was winning.

That week at practice, mentally and emotionally drained, Kyven’s head was anywhere but on wrestling. Sometimes stepping out of the wrestling room to regain his composure or ending his practice completely, the only place Kyven wanted to be was with his dad. But Willie told him to go to Stillwater, and Kyven did just that, promising to return with a first-place medal for Willie — just one piece of the lifelong puzzle the two had been working to complete.

Once at the Big 12 tournament, Kyven still did not want to be there with the knowledge his father could pass at anytime, even with his family’s blessing. After the first match of the tournament, just like at the beginning of the season, he went to Jackson and told him he was going to leave the Big 12 tournament.

“His heart, his mind and his soul just wasn’t there,” Jackson said. “He broke down after that match in the locker room and said he didn’t want to be there, just like any person would in that situation. I told him if we need to get you home, we’ll get you home.”

But Kyven stayed because that’s what Willie wanted, and he won because that’s what he told Willie he would do.

After the match, when Kyven had his hand raised, all the emotions he was bottling up bubbled over, and he let it go.

“Me and [Blake] Rosholt had some words, and the Oklahoma State crowd called me some choice names,” Kyven said. “I wasn’t really in a good place right after that match, and I know I had some words with Coach Jackson after that. [The coaches] kind of had to snatch me up and had to put me in my place a few times because I was so distraught in that situation. I really didn’t want to be there anyway, so what they were saying I just wasn’t trying to hear it.”

The ride home from Stillwater was calming for Kyven. As he sat listening to the same oldies songs he and Willie had listened to all those years ago on their way to wrestling tournaments, Kyven was back in the passenger seat of his dad’s car for a moment with Willie behind the wheel — just the two of them.

Kyven finally made it home and to his father’s side. He gave Willie the medal he had promised him, and although Willie didn’t respond, Kyven said he knew he was listening.

At 11:38 a.m. on March 10, 2013, just one day after the Big 12 tournament, Willie Gadson died.

***

Kyven stepped onto the mat on Feb. 23, 2014, as the recognized No. 1 wrestler at 197 pounds. Across from him stood University of Minnesota’s Scott Schiller, the same wrestler who had beat Kyven in the fifth-place match of the 2013 NCAA Championships just 13 days after Willie’s death.

Denita sat in the stands of Hilton Coliseum and watched her son beat Schiller, against whom Kyven had not won in three prior matches. Aside from joy, Denita felt something else as Kyven walked off the mat.

Admiration.

“He’s had his own issues with his health, and going into the Minnesota dual, he was also sick,” Denita said. “One thing I admire about him — and I know it is something about the way his dad trained him — is that he is not going to duck and he’s not going to make excuses and he’s not going to not show up.

“I admire that — that he put aside, that he could save his energy, that he could probably not wrestle because he might not be feeling his best … I admire his integrity, I admire his work ethic that my husband instilled in him.”

The 2014 season has not come without trial, as for the first time in his life, Kyven entered a wrestling season without his father.

“Earlier in the season he was really struggling with starting the year without his father,” Jackson said. “He gathered himself and kept moving forward. He’s matured as a young man, and I don’t think he’ll ever get over the fact that he’s lost his dad at such a young age, but he’s where he needs to be to do something special.”

As the Big 12 tournament nears, Kyven is ranked No. 1 in a sport ruled by the ferocious, the fast and the strong. But Kyven’s strength, just like Willie’s, is not the type that can be built in the weight room or on the mat: it can only be learned and taught by coaches and fathers.

And the lessons for that type of strength never come easy.