ISU professor named co-coordinator of U.S. swine genome program

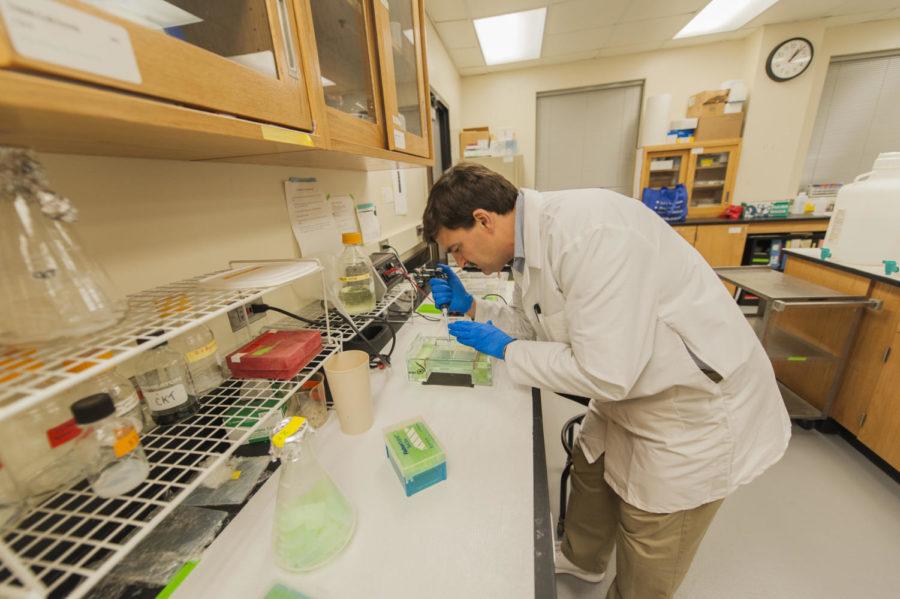

Yanhua Huang/ Iowa State Daily

Chris Tuggle works on genetics research in the Kildee Hall. He was selected as a co-coordinator of the U.S. Swine Genome Coordination Program, along with Cathy Ernst, of Michigan State.

October 29, 2013

Chris Tuggle, ISU professor of animal science, has been selected as the co-coordinator of the U.S. Swine Genome Coordination Program.

The program allows many different scientists to collaborate on multiple projects dealing with improving pigs as a whole, with some funding from the state, Tuggle said.

The program is currently trying to create pigs that need less feed, are more disease resistant and can cope with heat better in the wake of global warming.

“We’re coordinating people’s efforts and trying to facilitate collaborative research,” Tuggle said about his position.

Tuggle was elected to the position of co-coordinator on Oct. 1. The other co-coordinator, Cathy Ernst, was also elected at this time.

Ernst, professor at Michigan State, said it was advantageous to be located in a different state than Tuggle because it allowed them to oversee different areas of the country. She also said that communication is also not a problem because they use Skype and video conferences to interact.

“Tuggle is probably one of the leading swine genome researchers in the United States,” Ernst said, also noting that Tuggle’s leadership would be valuable to the program.

Tuggle said Ernst has more experience with animal breeders than he does, which he believes will make them a good team.

“We complement each other,” Tuggle said.

Tuggle said he started at Iowa State in 1991 after receiving a degree in chemistry and a doctorate in biochemistry, also doing post-doctorate work.

He and his wife both grew up in the Midwest and wanted to return, so he took a job at Iowa State where he would focus on mice and large animal genetics, which were controversial at the time due to the discovery of the ability to put genes in mice and to make them bigger.

After that, Tuggle began to focus mostly on pigs, due to the fact that it was discovered that pigs have more of a similar physiology to humans than mice do. He said one of his most notable studies was how to improve the immune system of a pig through genetics by trying to specifically target the genes that made pigs more vulnerable to salmonella and the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome.

“As animals are faster growing, they are more susceptible [to disease],” Tuggle said.

Collaborative work was also something Tuggle participated in before he became co-coordinator for the swine genome program. A program he worked in partnered with a team from the United Kingdom, which had a software tool that helped find and identify certain genes.

“We did that for 1,400 genes,” Tuggle said. “We worked with genes involved with the immune response. You do one gene at a time. It might take one hour or two hours or three hours to get that gene figured out.”

Now, Tuggle helps to coordinate collaborations between various scientists involving studies with pig genetics.

“We try to bring scientists together and introduce them,” Tuggle said. “The biggest goal is to further understand the pig genome and to develop tools to understand these traits.”

Tuggle said he will be responsible for not only coordinating meetings but also writing reports on what other people are working on. Although he will have more responsibilities, Tuggle said it should not affect his ability in class because most of the meetings are on weekends or in the summer.