Belding: Character education more important than specific knowledge

Photo: Blake Lanser/Iowa State Daily

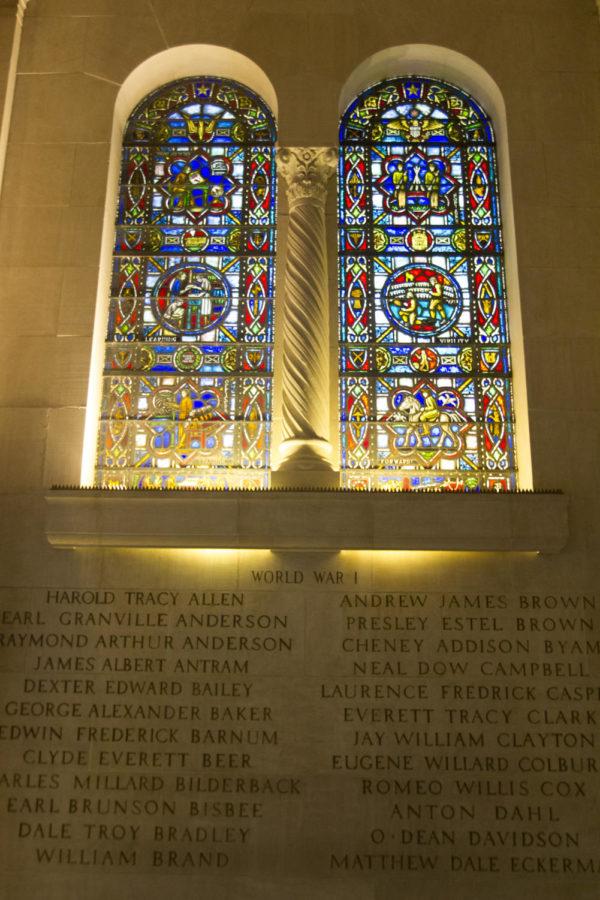

As a part of the Gold Star Hall, an entrance to the Memorial Union, stained glass windows illustrate the primary virtues an ISU student should strive to have: learning, virility, courage, patriotism, justice, faith, determination, love, obedience, loyalty, integrity and tolerance.

May 6, 2013

The Memorial Union’s Gold Star Hall serves as a continual reminder of the sacrifices that must be made to survive, with the names of ISU students who died in American wars since 1917 engraved on its walls. Above eye level, 12 panels of stained glass portray scenes and symbols related to Iowa State, its mission and the ideals of a virtuous life.

Indeed, the stained glass windows to which our eyes rise after reading the names of the veterans who gave the “ultimate sacrifice” are the qualities for which they fought. The first of those, which is most important for Iowa State and is probably on everyone’s mind this finals week, represents learning.

I won’t belabor the depictions in the glass itself. You can see it yourself, in the facade Iowa State presents to the world, or read the explanatory pamphlet on the Memorial Union’s website. “Learning” includes military training, library research, classroom teaching, religious symbols and the creation of our land-grant agricultural school. Such inclusion suggests that an education should do more than simply prepare students to obtain a job.

The first president of Iowa State understood that. At the very least, he paid it lip service in his inaugural address. On March 17, 1869, Adonijah Welch said, “Let every earnest youth strive for the attainment of that sort of intellectual power which, while it prepares him for the duties of the citizen, will enable him to do thoroughly and well his special work in the world.” Welch anticipated that the Iowa State Agricultural College would graft onto the liberal education offered by older colleges something that would benefit students as they worked to make a living: an education in agricultural science or a branch of engineering.

The window in Gold Star Hall, however, epitomizes the liberal education that Iowa State has more or less forsaken in the nearly 150 years since the state of Iowa designated it as Iowa’s land-grant college.

One of the most succinct definitions of a liberal education lives in the Englishman Henry Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Fowler defined a liberal education as one in which no expense is spared or which leads to broadmindedness in the student. On the opposite side of the educational spectrum is a technical, professional or otherwise specialized education.

In “The Radicalism of the American Revolution,” historian Gordon Wood clarified the point: A liberal education will instill in students the qualities of thinking and acting like gentlemen. Such thinking and acting, he wrote, “implied being reasonable, tolerant, honest, virtuous and candid, which meant just and unbiased as well as frank and sincere. It signified being cosmopolitan, standing on elevated ground in order to have a large view of human affairs, and being free of the prejudices, parochialism and religious enthusiasm of the vulgar and barbaric.”

In other words, a liberal education — such as the one advocated by that monument of artistic glass in the hub of Iowa State — is supposed to give context to our particular work so that, in single-minded pursuit of the tasks through which we make a living, we despoil neither the natural resources of the world nor the interactions we have with other people.

Perhaps like Karl Marx, who lamented the mechanization of the workplace (“The bourgeoisie … has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his ‘natural superiors,’ and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment.’”), I believe that humans are more than unthinking cogs in a machine whose operation has no consequences for the world in which it operates.

Acting in such a way that we are good stewards of the earth, and of ourselves, requires perspective, not merely empirical knowledge. The manner in which we apply the information imparted to us is just as important as the information itself.

Yet, who has known a 20-year-old to make good judgments on a consistent basis? From my own experience, more often than not I have acted recklessly. Truly, youth is wasted on the young. Since it would be too dangerous to allow us to learn morals on our own, someone must (in the words of the Bible) “Train up a child in the way that he should go, / [So that] when he is old he will not depart from it.”

Just as college curricula now should include job training, it should include the morals and perspectives necessary to do that job responsibly.

Michael Belding is a graduate student in history from Story City, Iowa.