Looking back at Iowa State after Pearl Harbor, 80 years later

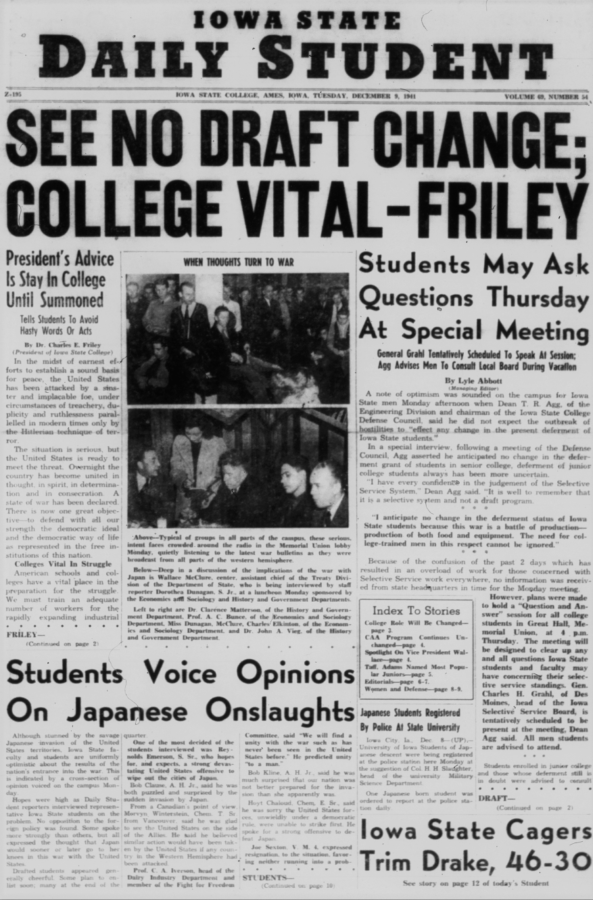

The front page of the Iowa State Daily Student discusses whether or not the draft will change due to the attack on Pearl Harbor that ushered the U.S. into WWII.

December 6, 2021

Eighty years ago, at the start of finals week at Iowa State, the Empire of Japan attacked the United States on the island of Hawaii, killing over 2,000. According to the Dec. 9, 1941 issue of the Iowa State Daily Student, students flocked to radios to hear Franklin D. Roosevelt deliver a speech the day after the attack. Students continued to follow updates—or try to avoid them, as one excerpt reads:

“Although most students with classes Monday morning were fortunate enough to have a radio in the room or were excused to hear the President’s message, it is wishful thinking that we’ll be able to keep in touch with the world situation while attending classes during the day. In your off hours come to the Union to hear the news reports, or if need be, for a relaxing hour to forget them.”

Following Roosevelt’s speech, a declaration of war was approved by both the Senate and the House, with only one representative, Jeannette Rankin of Montana, voting against it. A columnist in the Daily Student included a quote from someone on campus, saying that “when Miss Rankin voted against the declaration of war, she betrayed the patriotism of American women.”

In the present, Timothy Wolters, an associate professor of history at Iowa State, summed up the general attitude of United States citizens at the time.

“Americans are isolationist, they’re concerned about what’s going on in Europe, they’re very angry that one hundred Americans have been killed in a German U-boat attack on [the USS Reuben James], but not so angry that they’re clamoring for a declaration of war,” Wolters said. “And then the attack on Pearl Harbor happens, and that’s when the United States decides to go to war [with Japan].”

Wolters said that many Americans were shocked and angered by the attack. The issues of the Iowa State Daily Student that were published the week after Pearl Harbor showed various responses alongside advertisements featuring Santa Claus and the usual news about campus. Many students likely had known that the United States would enter the war eventually, but they hadn’t known when.

“I didn’t expect this to come so soon; the Christmas attitude this year is going to be different from anything we’ve ever seen,” one student said.

Some students seemed relieved. A columnist by the initials “D.J.” wrote: “Few have doubted for the past year that our entrance into the conflict was imminent, but we have lived miserably from day to day in the cloak of procrastination and muddled uncertainty…Though our future is not a bright one, we no longer are tottering on the brink, we have taken the plunge.”

Many compared the situation after Pearl Harbor to that of the start of World War I. Harold Pride, then-director of the Memorial Union, said that Iowa State students had “a far better understanding of world conditions than in 1917,” citing advancements in communication technology, such as radio.

A Chinese student wrote in a letter to the editor stating, “everything seemed to be normal and there was no excessive excitement,” saying that “the United States is many times better prepared than China was at the beginning of her hostilities with Japan.”

News of the attack and the declaration of war caused a distraction for many students during finals week, as evidence by several quotes from opinion articles and interviews with students:

“It is easy, in these days of war, for people of college age to become depressed… What’s the use of exerting effort toward studies or work, we may ask, when all there is ahead is the bitter sacrifice of war?”

“We turn to our radios and hear horrible, unbelievable reports of world catastrophe. And then we turn to our books, to chemical formulas and the principles of grammar. We cannot avoid the feeling that what we are doing is trite and useless,” another student said.

“A few students reported they had let down their efforts in school work in the face of inevitable induction into the service. Most students, however, have decided to continue as before, come what may,” another student said.

Shortages of items such as art supplies and food used in nutrition classes were anticipated, as metal and other resources would be needed to support the military. Many students decided to enlist, and the declaration of war apparently made some students rethink their life decisions.

“I wish now that I’d taken a nurses training course instead of coming to college,” a female junior said.

Following Pearl Harbor, Iowa State President Charles Friley told students to “exert every effort to view the situation realistically, to avoid hasty and intemperate words or acts and to search out courageously [their] individual duty and obligation in the defense of the common cause.”

He advised them to continue their education until they were called for service, calling for “a vigorous offensive against passive and indifferent loyalty, against outright disloyalty and against inactive and uninformed citizenship.”

In many ways, similarities can be seen between how people responded to Pearl Harbor and the start of the COVID-19 pandemic at Iowa State. In an email sent on March 27, 2020, President Wendy Wintersteen included a quote from Ruth V. Watkins, then-president of the University of Utah, which said, “Stay on your academic paths. The rewards for doing so will last a lifetime, long after the coronavirus pandemic fades.”

In an earlier email, sent on Feb. 28, 2020, Wintersteen also made calls to action. In addition to information on preventing the spread of the virus, she said that everyone had “a responsibility to limit the spread of misinformation” and encouraged those on campus “to speak out against negative and stigmatizing behavior.” 2020 saw a 73% increase in reported anti-Asian hate crimes, which rose from 161 incidents in 2019 to 279 the next year, according to the FBI.

After Pearl Harbor, the notion that people of Japanese ancestry living in the United States would be the targets of heightened racism was immediately apparent.

“Many Japanese people will be ridiculed and injured—some of whom are striving to uphold the ideals of the new country they have adopted,” a columnist said.

The front page of the Dec. 9, 1941 issue of the Daily Student reported that at the University of Iowa, “students of Japanese descent” had been registered by police, and that “one Japanese born student was ordered to report at the police station daily.”

Eventually, suspicion against Japanese Americans would lead to Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced internment of about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry over the course of the war.

One year before the attack, the first peacetime draft in U.S. history had been enacted. A report on students’ opinions on the front page of the Dec. 9 issue said that “no opposition to foreign policy was found” and that “drafted students appeared generally cheerful.”

Amy Rutenberg, an associate professor of history at Iowa State, provided some context on how the peacetime draft was received.

“It was a controversial measure as it was making its way through Congress,” she said. “Once it passed… most people didn’t have a whole lot to say. There were pacifist organizations who were active at that time, and also that overlapped with groups that wanted to stay out of the war and so they weren’t terribly pleased with the fact that the draft existed.”

On the Thursday following Pearl Harbor, a meeting was held in the Great Hall of the Memorial Union to answer students’ questions about the draft and “chart the course of their immediate future in view of the national crisis.” The next day, male students were expected to attend meetings at five locations across campus to provide information to the Selective Service.

A humor columnist made light of the situation: “As soon as our draft number comes up, we’re going to wait for an opportune moment and tell some of these profs some of the things we’ve been saving up for a long time.”

The subject of the draft has received coverage in the news recently, due to legislation introduced in Congress that would require women to register for the Selective Service. Rutenberg expressed doubt that the United States would implement a draft any time in the near future.

“The military has no interest in having a conscripted force… it’s helpful if your personnel actually choose to be there, as opposed to being conscripted and forced to be there…,” she said.

She added that wars are fought differently today than they were in the past and that it wouldn’t be worth the investment of time and money that currently goes into training service members if they were going to leave after two years.

“The United States was attacked in 2001, and we did not move to a draft,” Rutenberg said. “The United States has fought two wars since 2001, and we maintained an all-volunteer force through that.”

After the attack in 1941, many understood that they faced uncertain and terrifying futures. As one student wrote, “There is not a student on the campus whose life will not be altered by what happened Sunday. Most of the men expect to see service under fire in months ahead… A way of living is slipping away from us, and we may not have it again for a very long time.”