Content warning: This review contains discussions of suicide.

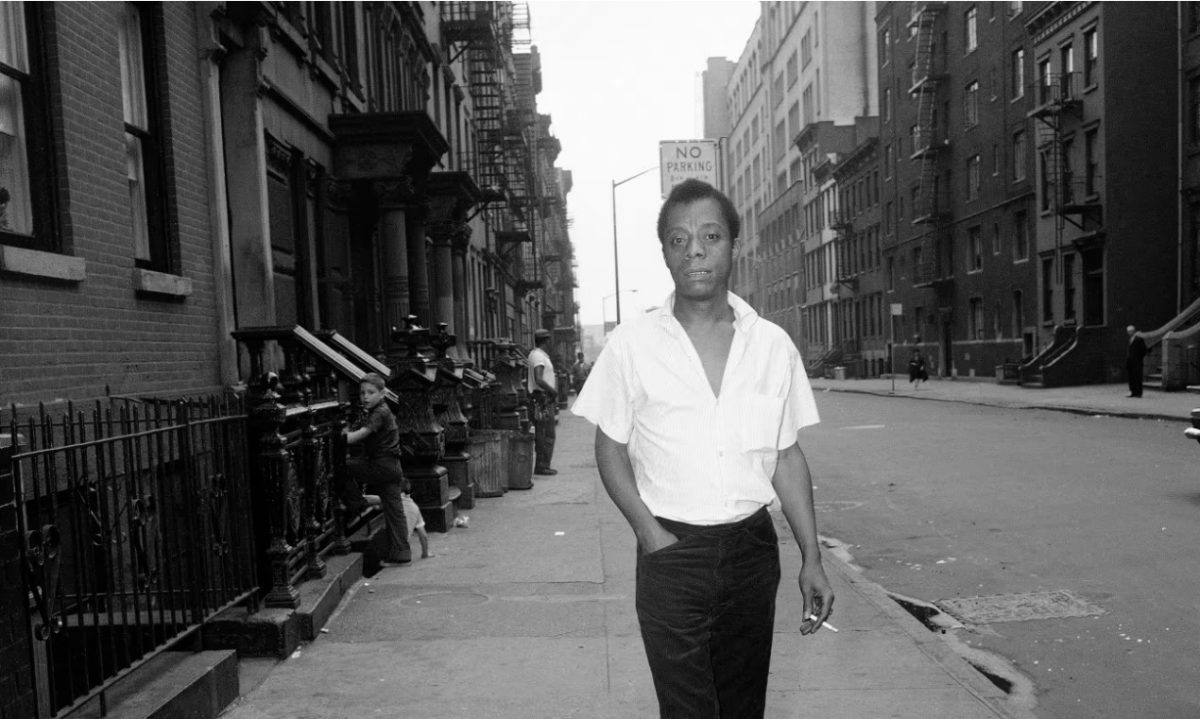

“Then, perhaps, life only offers the choice of remembering the garden or forgetting it. Either, or: it takes strength to remember, it takes another kind to forget, it takes a hero to do both. People who remember court madness through pain, the pain of the perpetually recurring death of their innocence…and the world is mostly divided between madmen who remember and madmen who forget. Heroes are rare.” – James Baldwin

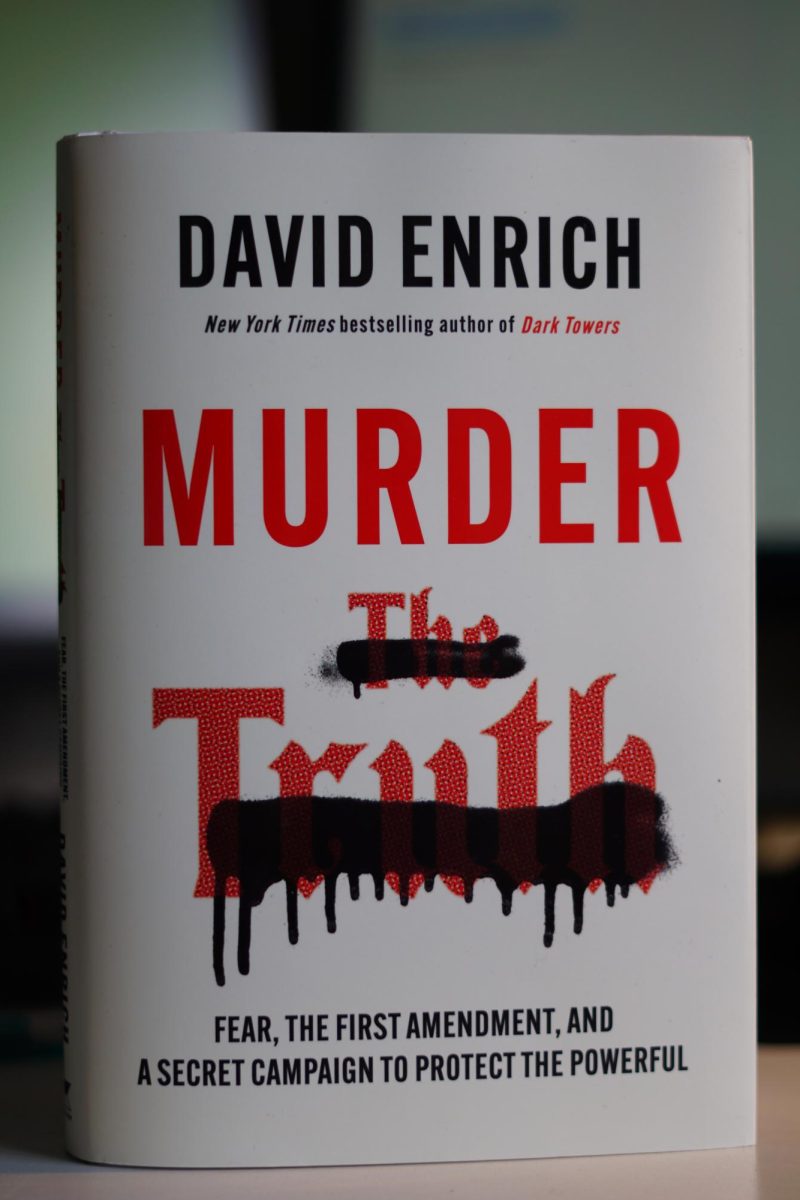

Next in the review series is James Baldwin’s legendary novel “Giovanni’s Room.” First and foremost, I am happy to report that readers are enjoying the book reviews. It is something I plan to continue, so thank you to all who take the time and care to read them. Now, to the context of the novel.

For a chunk of my time here in Ireland, I have been immersed in Baldwin’s novels. It happened randomly. I was touring the bookshops around Cork, and it was my last stop where I found “Giovanni’s Room.” Although I had heard much about it before, I never had taken the step to read the novel. I was aware of Baldwin’s brilliance with words and ideas since I read “The Price of the Ticket,” a large collection of essays, but I never sat down with his fiction.

Baldwin poured himself into everything he wrote. That is obvious. Not solely his energy, but his story, purpose and, most importantly, his suffering. The translation of this suffering gave his work, both fiction and non-fiction, that gravity that is often ascribed to them. “Giovanni’s Room,” in particular, is one such instance.

In 1948, Baldwin relocated to Paris from Harlem, a neighborhood in New York City where he was born. Upon arrival, he had 40 dollars in his pocket. Explaining his rationale for the move, Baldwin asserts that it was because he could no longer afford the situation in the United States. His best friend had already killed himself, and he would follow soon after. In America, Baldwin summarizes his feelings:

“My reflexes were tormented by the plight of other people. Reading had taken me away for long periods at a time, yet I still had to deal with the streets and the authorities and the cold…My luck was running out. I was going to go to jail, I was going to kill somebody or be killed.”

In Paris, he could escape the tense racial discrimination in America. Baldwin continues to say that his move “wasn’t so much a matter of choosing France—it was a matter of getting out of America. I didn’t know what was going to happen to me in France, but I knew what was going to happen to me in New York. If I had stayed there, I would have gone under, like my friend on the George Washington Bridge.”

And it was not his race alone that made Baldwin uncomfortable in America. It was also the fact that he was open about his sexuality. He refrained from labeling himself as “homosexual” or “gay,” but Baldwin also did not hide his open sexuality from the world. In fact, “Giovanni’s Room” is an example.

The main character and narrator in the novel, David, meets an Italian bartender named Giovanni in Paris. David is also waiting for his fiance, Hella, to return from Spain, where she sought to ponder David’s proposal for marriage. In the time that David waits for Hella, he begins to fall in love with Giovanni. However, David also faces damaging internal tensions. He knows that society will never allow such a relationship. But this idea is plaguing itself. David venerates the limits of societal expectation instead of carrying out what his love most desires—crumbling Giovanni and Hella in the process. David lives a sort of double life. One in Giovanni’s room—where he finds himself happiest—and one outside of Giovanni’s room, which is one of pain and torment. Within David lies a dualism I believe Baldwin attempts to illuminate. David possesses burning passions of love and attachment and happiness. Still, he is also forced to balance this passion against the cold iron walls of his heart, which is put off by society and convinced of its own wickedness.

What is more, we are let in on the ending of the novel in the first couple of pages. Giovanni does something that condemns him to death by guillotine. What this act is, we are not certain. Baldwin keeps readers interested by dropping signals to the novel’s climax throughout the book. This allows one to trace the downfall of each character, even if everything seems to be relatively optimistic. Such an act causes one to ponder the lingering tragedies that inevitably face us all. Baldwin is truly an expert psychologist and sociologist in this way.

In any case, there is no doubt that you should read this book. It is also relatively short, so if you want an introduction to Baldwin’s writing, “Giovanni’s Room” is a great place to start. It touches on themes of shame, guilt, loss and, most importantly, love—something I believe we all know a little about but often fail to navigate.

Rating: 9.5/10