Felker: There isn’t enough STEM in my coffee

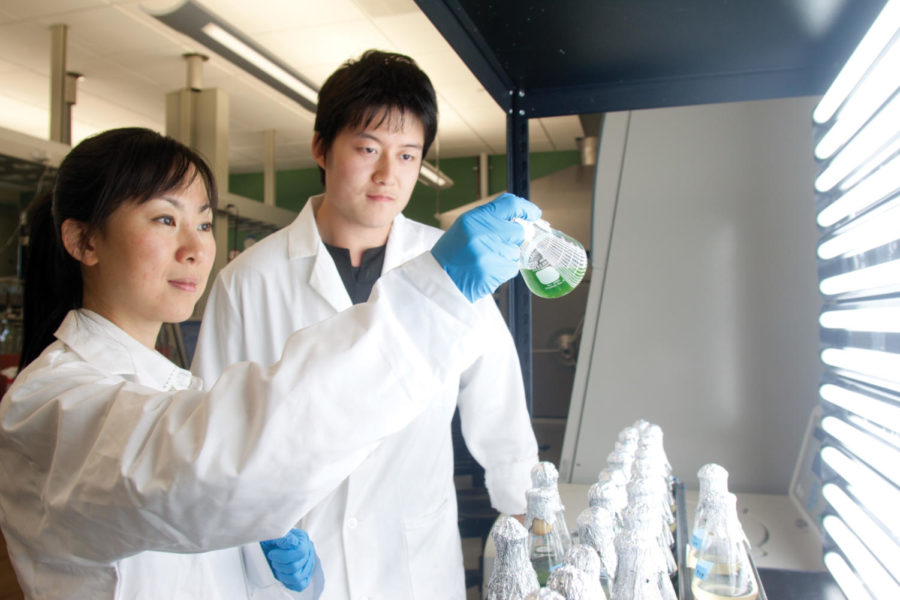

Photo: Tessa Callender/Iowa State Daily

Yi Liang and Yitian Sun examine beakers of algae Sept. 21, 2011. The lipids extracted from the algae are helping to make a renewable biofuel they are working on creating in the Hybrid Processing Laboratory in Iowa State’s new Biorenewables Research Laboratory.

April 10, 2017

As a soon-to-be Iowa State graduate, I must admit one of my favorite pastimes to be making fun of engineering students. It’s too easy. There’s a common misconception — wholly untrue, but wholly amusing — that all our school’s engineering colleges turn out is a horde of politically, culturally, ethically disinterested number junkies and pencil pushers. And while this may be an entertaining typecast, I’ve found nothing to be further from the truth.

The truth, in fact, is that I admire them. These are enterprising, energetic, hard-working young men and women, and I’ve found their enthusiasm to be no less applied to social or moral thoughtfulness than to their empirically involved studies.

But this is beside the point. Iowa State churns out these qualified persons in buckets and droves, and what I argue is that our liberal arts and humanities majors actually need themselves a bit more STEM in their coffee. That’s Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. It’s a trendy acronym nowadays, and one that Iowa State has really taken to heart; it’s our mantra. But there’s a pretty startling divide between the university programs’ curricula of study.

I believe every English major ought to minor in a STEM field. Every history major, every communications major and every philosophy major ought to do the same. There’s something to be said for context, and a university education without it is not really a university education at all. Common criticism runs that these arts or humanities graduates are unprepared for the workforce, and, while I think this largely a delusional platitude, there is a grain of truth in every fallacy’s core.

The liberal arts and humanities curricula of our state’s universities need to be adjusted. More than these students simply and deeply immersing themselves in literature and theory and commentary, they need some introduction or background in STEM to contextualize the kind of issues they’ll be asked to face — in not just the coming job market, but in all our future society’s framework. This kind of systemic change needs to be adopted by the university, not just by each individual college, and it’s the curricula of these humanities majors themselves that need to be altered.

Our economy won’t stop moving forward for the old order’s sake. Statistics, information systems, network technology, the physical sciences, all the manifold sorts of engineering and many more technical fields besides — with each day and each week these fields are made a more ingrained, meaningful piece of our culture.

To ignore this pattern would be to all our communities’ detriment. The student deserves and requires a round education — and I absolutely support the kind of cross-germination described above. It can take many forms, but I will illustrate just one, explicitly, to further explain my point.

In one of ISU’s buildings, there is a bulletin board — that I see every week — that advertises a very unique program: a three-year MFA in creative writing and environment. This is “a program of study that includes a rigorous combination of creative writing workshops, literature coursework, environmental fieldwork experience, [and] interdisciplinary study in courses other than English.”

This is a great example of what an holistic education could be. Why aren’t there more programs of study like this? Why not pair a training in Greek and Roman infrastructure and development with modern mathematics? How about a study in ancient sociology combined with statistics? Or maybe philosophy and technical political science? I make these recommendations not merely because certain fields naturally complement each other, but because a STEM education cultivates problem-solving skills, perspective and innovation — all in ways with which many arts and humanities students are unfamiliar.

I understand that many of these suggestions I make are already well possible — the framework exists for them at each and every regent university and many more besides. But I argue this concept ought to be enforced on an actually regulated basis, for the benefit of the state, the institutions and the students. It ought to be required. If our regents are truly committed to “learning that empowers excellence,” then I urge them to take a leadership role in this initiative.