Communication key when seeking consent

February 8, 2017

Trigger warning: This content uses language that may trigger sexual assault survivors.

Sexual assault is a complex and horrible issue. It is personal, it is heartbreaking and it is different in every case. But if we ever want to put an end to sexual assault, we have to stop letting its complexity get in our way.

This is the fifth story in a semester-long series where the Daily will publish a multitude of stories related to sexual assault, including discussions about various resources survivors can obtain if they are comfortable doing so.

— Emily Barske, editor in chief

Imagine you’re at a stoplight.

Red light means you stop. Green light means you go.

The same rings true with consent, which is why Green Light: Go! was created to raise awareness of consent and sexual assault based off a variation on the game Red Light, Green Light.

The game, which originated through the fraternity Zeta Beta Tau, has spread across college campuses around the nation, and hopes to “ignite a conversation on campus that can really make a difference.”

In sexual acts or not, consent is the act of agreeing or not agreeing to anything that would affect someone else.

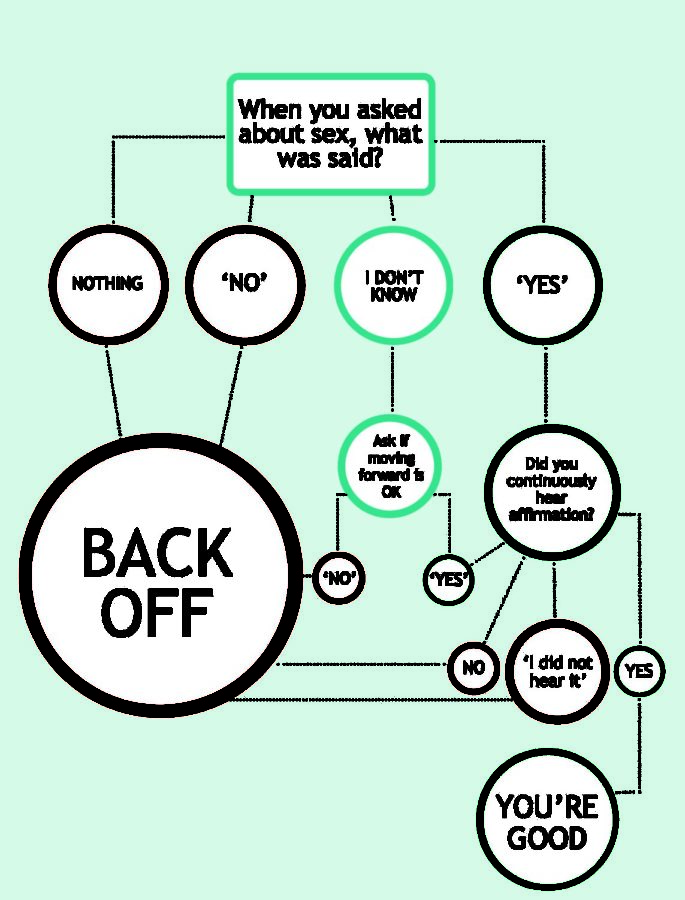

“Consent between two or more people is defined as an affirmative agreement — through clear actions or words — to engage in sexual activity,” according to the Office of Equal Opportunity’s (OEO) website.

Anthony Greiter, Iowa State police officer and community outreach specialist, explained that communication is the best way to receive consent.

“Conversation is key… There has to be some form of communication amongst all parties involved, and it has to be ongoing,” Greiter said.

Steffani Simbric, Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) coordinator, furthered the idea of consent.

“[In getting consent], someone has to ask,” Simbric said. “If we are in a room together, what your intentions are and what my intentions are might be two completely different things.

“Why would you not want to ensure that the other person is into what you want to do? It’s going to be a more enjoyable experience [if you are sure they want to].”

However, some people don’t always ask for consent, as they may be afraid of being turned down. Simbric enforced, however, that there still has to be a conversation about it.

“Relationship or not a relationship [between parties], it doesn’t matter,” Simbric said.

Margo Foreman, Iowa State’s Title IX Coordinator and director of the OEO, explained why there is controversy over getting consent.

“Socially, it’s not the way individuals perceive sexual relations, intimate partners,” Foreman said. “People don’t take the time to build a norm around what intimacy means. They spend less time engaging in deep contemplation around what it is to be partnered, to be intimate, where there are boundaries, what the vocabulary is.”

Foreman said that consent is about courtesy and respect.

“That means that people need to take more time and feel their gut,” Foreman said. “[You need to be able to know] when something is off, when to stop, to get affirmative consent throughout a sexual encounter. [Knowing what your partner wants makes the experience better]. Otherwise you are the orchestra and the conductor.”

The people who are not informed about what consent exactly is are the ones who need to “really dig in deep” on how to ask for and give consent the most, Foreman said, because those who do not know could be the next assailant.

“The potential victim is someone’s child,” Foreman said. “It could be someone’s sister or brother. It could be your sister or brother, or worse, it could be you.”

Taking a step back and looking at the big picture, consent is something that is given on a daily basis. Simbric said that consent on in its simplest form is even something she talks about with her 4- and 9-year-old children on a day-to-day basis.

“It’s interesting when you look at consent,” Simbric said. “[…] I’ll say your brother said ‘no’ so you need to stop doing that’ [whether they’re playing or whatever the circumstance may be].”

Greiter compared continuous consent to two people going for a walk. One person asks another if they want to go for a walk, and later on, that does not mean they start to go for a run. The person agreed to a walk, not a run.

“I think that is where [society stumbles]: asking the question [of getting consent],” Greiter said. “And the reason is that it’s uncomfortable […] people think it’s awkward or it has to be formal or a contract, and that is not true.”

When intoxication plays a roll, Iowa laws state that if a person is incapable of giving consent, consent is not granted.

Iowa Code defines “physically helpless” as “a person [who] is unable to communicate an unwillingness to act because the person is unconscious, asleep, or is otherwise physically limited.”

In other words, “in Iowa, intoxication means you cannot give consent,” Greiter said. “Somebody that’s intoxicated cannot legally provide consent, so if they’re drunk, they can’t provide consent, they can’t have sex with them.”

Suppose a partner consents and then says no or freezes or is silent, Greiter said. Consent is no longer granted due to tonic immobility.

“Humans are hardwired to protect themselves,” Greiter said. “If you are in a traumatic experience, oftentimes your brain will say, ‘I’m going to take you somewhere else so you can survive this traumatic experience.’”

Greiter described an example of tonic immobility as someone focusing on something separate from what is happening to them physically.

“There are victims who focus on a copy of a book on a coffee table,” Greiter said. “That’s what they remember… They don’t recall, readily, a lot of the details of what happened.

“If you’re staring at a book on a coffee table, are you focusing on what’s happening to you physically to say ‘no?’ Probably not.”

When the victim is “frozen,” there is also shock and trauma going on in that moment in more aggressive cases, Foreman said.

“Your body protects its inner core, get quiet and still and find a safe place. There’s displacement,” Foreman said. “You’ll hear, ‘It just happened,’ ‘I just wanted it over with,’ ‘I wanted them to hurry up.’ That is a way to typically deal with the trauma.”

OEO’s website states that silence does not mean consent has been given. This is no matter how far partners have gone already. Anyone can say no at any time, and other partners must be aware of when their partner is or is not OK with something happening.

In addition to intoxication, Iowa law states that those who are unable to communicate consent due to a mental or physical condition cannot be assumed that they give consent.

“… nor does silence mean consent has been given,” OEO’s website reads.

Foreman said the lessons and rules that are enforced on campus apply to the world.

“These are lifelong issues that you should not only uphold, but you should teach them to your children when you have them,” Foreman said.

As outreach to the Iowa State community, Simbric and Greiter go around campus presenting information about sexual assault and its entities. The two reach thousands of people each year, Greiter said.

In addition, they, with the Iowa State Police Department and the Story County SART, host events around campus to spread awareness about the subject of sexual assault and misconduct, whether it’s handing out pins at Destination Iowa State or giving presentations.

Foreman and OEO train Iowa State faculty on how to be prepared if a student wants to confide in a staff member. Conversation shows sincere care, Foreman said, which makes people feel safe.

“If we can do that more, I think we’re going to see now some change in not only reporting but the consequences,” Foreman said. “The ultimate consequence of reporting is culture change. The more people that report, the more people held accountable, the greater the understanding is that accountability will matter.”