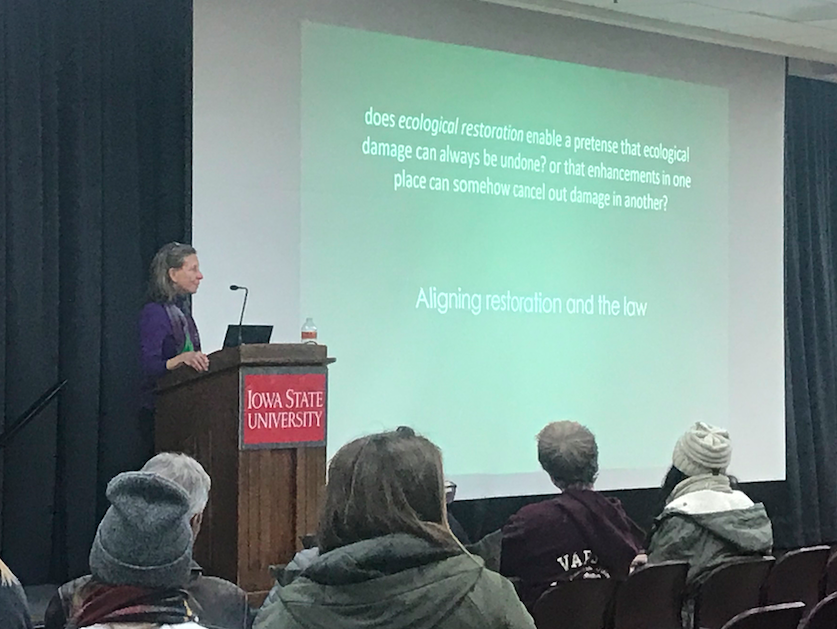

Margaret Palmer discusses restoration for America’s water systems

Margret A. Palmer from the University of Maryland gave a lecture about the restoration of streams, rivers and wetlands in America.

November 12, 2019

Margaret A. Palmer spoke about the restoration of America’s water systems and explained how the effects that humans have on water quality and how ecological, ecosystem, and mitigation processes can help reverse those effects Tuesday.

Palmer, professor of entomology at the University of Maryland, is a leader in restoration ecology and internationally known for her work in aquatic ecosystem science. Her emphasis is on steams, rivers and wetlands and how to improve the quality of the water within them.

Megan Hellman, a sophomore in architecture, was one of the many students in attendance of the lecture. She said she made note of the many examples of restoration Palmer demonstrated.

“I learned about lots of different case studies,” Hellman said. “[I learned about] the mitigation process and how sometimes it’s not as efficient as we think it is.”

This mitigation process is something Palmer is working to improve. Mitigation is the way humans can reverse the effects they have on their environment. To illustrate the process, Palmer explained a case study about the coal mining in the Appalachian region of the country.

Mountaintop mining is a practice using dynamite to blow up the tops of mountains to expose and collect coal. When a mountain top is blasted with dynamite, the excess materials fill streams and bodies of water.

Palmer said these excess materials have not been exposed to the air for a long time, making them very high in magnesium, calcium and other elements. When water is exposed to these materials, it negatively impacts the water’s quality.

The result is a “toxic soup,” according to Palmer. The water’s pH level becomes highly alkaline and acquires a chalky-like appearance. Furthermore, the habitats and species within the streams impacted are destroyed.

In order to counteract these effects of mountaintop mining, drainage ditches are implemented and streams are rid of the excess rock material, according to Palmer. These mitigation projects are monitored over the course of five years to ensure their efforts are consistent.

Paige Rolle also attended the lecture. Rolle is a freshman in civil engineering and said she didn’t have much prior knowledge on the topic of restoration.

“I didn’t know that there were so many different restoration processes,” Rolle said. “It was kind of cool to learn about those.”

In addition to the mitigation processes, Palmer also addressed a case study involving ecosystem restoration. In this particular study, streams near Maryland’s coast were being impacted by the result of agricultural practices.

Palmer said nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, along with excessive amounts of suspended sediments flow into streams. The goal of this case study was to manipulate the route water took to the stream.

The creation of “step pools” allowed water to collect and settle after a stormflow before emptying into a stream. When the water has the ability to sit unmoving, denitrification can take place and the unwanted debris can settle instead of being deposited into streams and rivers.

Palmer said restoration is never easy for scientists and it is not always recognized as a science. She said the social dynamics around the topic are changing and restoration is becoming more prevalent especially with the midwest’s agriculture.

“I think being educated is the first step [to understanding],” Hellman said. “With [agriculture] in Iowa, we need to get more involved […] with the water processes and being more proactive instead of reactive.”