Snyder: Police officers overstepping boundaries causes danger

Jessica Kline/Iowa State Daily

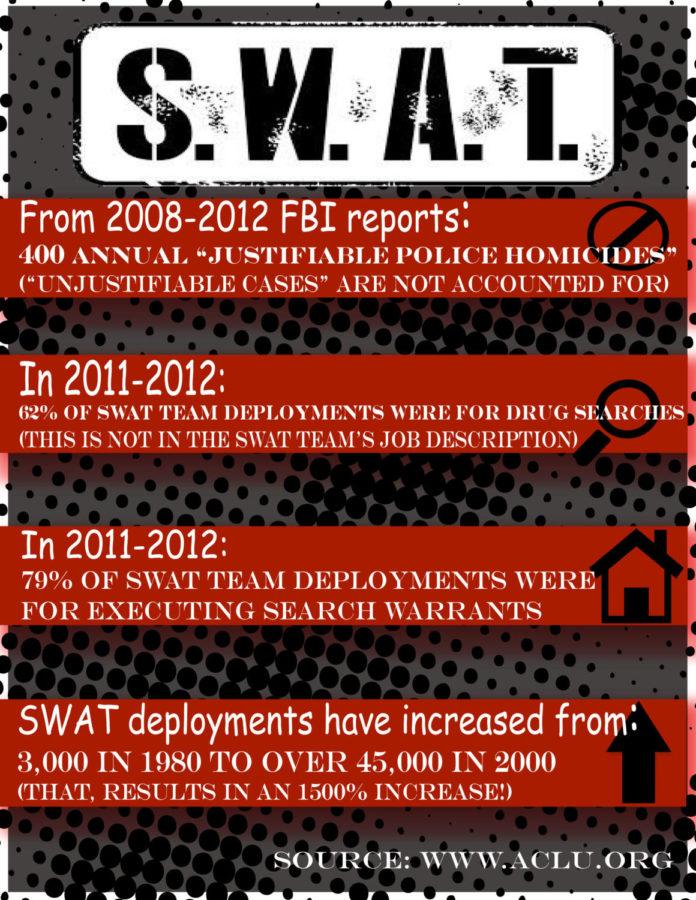

Infographic: SWAT deployment statistics

October 22, 2014

The only time police officers get national recognition seems to be when we are noting them for doing their jobs incorrectly. Many police officers and those that stand up to support them call on this fact when law enforcement is met with controversy — the argument they make is: why aren’t we talking about all the police officers who consistently get it right and are truly a positive presence in their community?

These arguments are certainly based in fact. There is no doubt that the overwhelming majority of police officers act responsibly and react appropriately in situations that would make a regular citizen panic, jump to conclusions and act without forethought. I do think that these good police officers need to be recognized for their work, but if even one police officer, or any other enforcer of the law, acts like a regular citizen, the heightened national awareness is warranted.

Since the 1990s, local police forces have been obtaining military grade equipment from the government under Programs 1028 and 1033 which allows the Secretary of Defense to transfer property of the Department of Defense, including small arms and ammunition, to local law enforcement. The requirements being that the police departments prove it’s necessary for their work and the Department of Defense doesn’t need it. This isn’t just a large city issue. It extends even further than mid-sized cities like Des Moines, as police departments in Story County and communities as small as 7,000 people have also received these donations from the Department of Defense.

Now, as any statistician knows, association does not necessarily prove causation, but the following patterns are somewhat distressing. According to a research paper titled “Militarization and Policing—Its Relevance to 21st Century Police” by Peter Kraska, professor of justice studies at Eastern Kentucky University, the deployment of Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) teams by police departments has increased from just around 3,000 per year in the 1980s to 45,000 in the year 2000.

The paper was published in 2007, and the statistics used were from a 2001 book which Kraska published, so no further information is available, but if the numbers have increased, as the projected path and ever decreasing police oversight would suggest, the numbers are even more disturbing.

This information can be interpreted in two ways. One, our society is in such a state of disrepair that such a high volume of SWAT deployments have become necessary. This reasoning falls flat in several fields of analysis, most notably the fact that overall national crime rates as well as violent crime rates have consistently decreased since the 1980s. Some may say this is a result of SWAT team deployment, but SWAT teams are typically only used after or while crimes are being committed.

The second and more likely answer is that the way our police departments use SWAT teams has changed. Where SWAT teams were most frequently used in hostage and active shooter situations, they are now used as agents of the war on drugs.

According to an American Civil Liberties Union study, 62 percent of SWAT deployments were in conjunction with drug searches. Additionally, 79 percent of SWAT deployments were for the purposes of executing search warrants. That is quite patently not the responsibility of SWAT teams. The police departments get away with these practices by labeling search warrant situations as high risk. Even though that term is sometimes applicable, the assigning of the term is often completely arbitrary.

SWAT teams are the most clearly militarized branches of police departments, which is why using them for one-size-fits-all searches presents increased risk to civilians. Only further enhancing the risks associated with using SWAT teams to execute search warrants is the growing prevalence of “no knock” searches. Kraska described these searches in the same 2007 paper.

No knock raids “constitute a proactive contraband raid. The purpose of these raids is generally to collect evidence, usually, drugs, guns, and/or money, from inside a private residence. This means that they are essentially a crude form of drug investigation. A surprise ‘dynamic entry’ into a private residence creates conditions that place the citizens and police in an extremely volatile position necessitating extraordinary measures.”

Examples of the dangers presented by no knock raids can be found all across the nation. Take for example the case of Jose Guerena, the ex-Marine who served in Iraq, but was killed by SWAT officers in his own home. When Guerena’s girlfriend saw shadows on their window, Guerena grabbed his legally owned rifle. He then stepped into his kitchen and was fired upon excessively by police officers, who then denied him medical assistance for over an hour as he bled to death.

Even more chilling is the story of the Phonesavanh family. The home they were staying in was raided by police officers, during which a flash-bang grenade was thrown into the crib of their infant son. The baby boy lived, but the grenade exposed his ribs and gave him third degree burns.

Finally, the case of Henry Magee, who had his home raided by SWAT in the middle of the night, and believing that he and his family were experiencing a home invasion, killed an officer with his firearm. He was initially charged with capital murder, but was not indicted on the charge when it went to a grand jury. This grand jury decision is evidence that the American public does not support any type of no knock system or the militarization of the police.

All three of these instances are tragedies. The practice of no knock raids not only puts citizens in unnecessary danger, but the same can often be said for the officers executing the raids.

According the Uniform Crime Report, published by the FBI, police departments and other law enforcement agencies are responsible for 400 “justifiable homicides” per year (based on the average number of justifiable homicides between 2008-2011). This number is supported by the Center for Disease Control’s report called the National Vital Statistics System.

However, the CDC also accounts for nearly 3,000 more homicides per year in the U.S. than the FBI. While not the largest factor in these numbers, the fact that there is no federal effort made to account for “unjustifiable” police homicides is certainly a contributing factor to the discrepancy.

Those “unjustifiable” homicides are simply discarded. There is no reliable national database to indicate the number of any such victims. If you are killed by the police, and they are found to be in error for having murdered you, the nation has no interest in your story. You aren’t even worth becoming a statistic.

This glaring flaw in the justice system of our country will only be corrected when public opinion forces change upon these agencies. They will never willingly make their jobs harder by providing these statistics, and why should they?

We lean on our local police departments for protection, not to become another source of fear. Police officers are held to a higher standard because more is expected of them. If we needed people walking around with firearms that react poorly to pressure situations leading them to shoot first and ask questions later, I could probably handle it myself — that is what a coward does.

However, I could never do what a true police officer does. I could never maintain the delicate balance between social figure and law enforcer. I could never make a place safer simply through my presence. So for all the good cops in this nation, and there are many of you, keep your heart in the right place.

While the fact is that our society increasingly relies on the police every day, that growing need also calls for clear minds and level heads. Not just empty uniforms with shiny badges and firearms with itchy triggers.