Up from below: Earl Hall’s journey into folkstyle

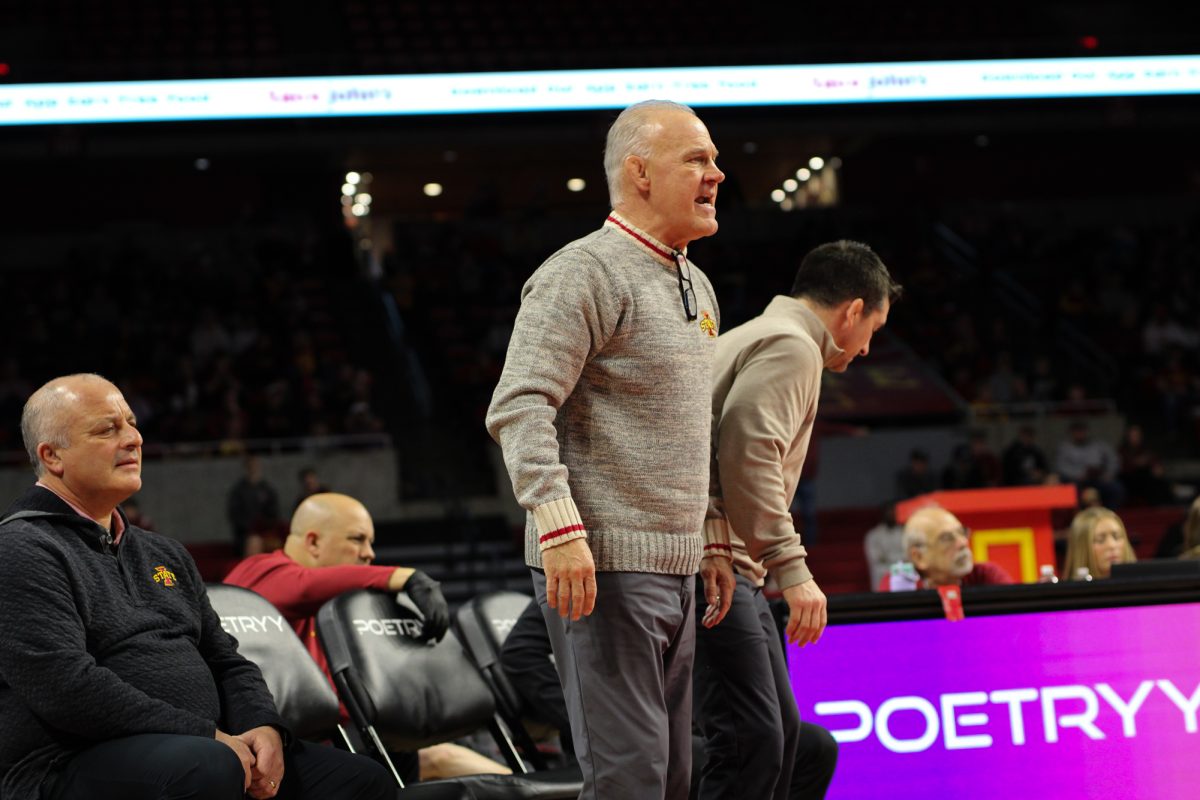

Brian Achenbach/Iowa State Daily

Sophomore Earl Hall, 125 pounds, gets thrown to the floor during his match against Iowa’s Cory Clark on Dec. 1 at Hilton Coliseum. Hall would lose by decision to Clark. Iowa State lost the dual to Iowa 23 to 9.

January 21, 2014

Earl Hall’s eyes dart from point to point as he talks, as if he’s not quite sure where to look, or tracking something as it zips through the air.

When he does makes eye contact, it is quick and to the point.

Hall’s body language is fluid. His posture is relaxed and his hands rest in front of his chest, his fingers interlocked in between the articulate gestures that aid his words.

For someone not familiar with Hall, it can be hard to read the stout, 125 pounder. For someone wrestling Hall for the first time, it can be even worse.

In his first year as a collegiate athlete, Hall has quickly gained notoriety among the Cyclone faithful for his erratic, yet fluid, moves on the mat. His quick, sudden takedowns have led the Homestead, Fla., native to a 14-7 overall record including five pins, tying him for most on the team.

The amount of adjectives that could be used to describe Hall and his style of wrestling are in abundance, however, it’s possible that none of those words can accurately embody the many facets of Hall’s technique. ISU assistant coach Troy Nickerson sums it up in the most simple way he can.

“He’s exciting,” Nickerson said. “You never know what’s going to happen out there on the mat with him. He can be in a tight match at one minute, the next minute he’s got the guy on his back and he’s pinning him, so he’s just that explosive and his style is one that we want to see out of all of our athletes.”

From the time he first picked up headgear, Hall’s style was molded by his father, who taught him to just “Go, go and go.” Hall’s ferocious takedowns and ability on his feet were honed as a four-time state champion in Florida, when he took on bigger wrestlers that he couldn’t pin.

Hall’s approach and philosophy to the takedown was simple: Get the takedown, break his opponent’s mental toughness, repeat.

After high school, Hall spent two years at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colo., training under the likes of Logan Stieber, a two-time NCAA champion currently at Ohio State, and Bill Zadick, a national champion at Iowa as well as 2006 world champion at 66 kilograms.

At the OTC, Hall was able to live, train and compete with the best wrestlers in the nation, and even the world. In 2012, Hall won the FILA Junior World Team Trials at 60 kilograms and also qualified for the 2012 U.S. Olympic Trials in Iowa City.

While his two years at the OTC were invaluable, Hall mainly practiced freestyle wrestling, an older genre of the sport that is different from the collegiate form of wrestling, commonly known as “folkstyle”.

“Bottom work, that’s the main thing,” says Hall of the difference between the styles. “[In folkstyle when] you take them down, you got to turn them, obviously, but if you don’t turn them in a certain amount of time you come back up to your feet and keep wrestling.”

Hall said the transition from freestyle to folkstyle has been tough. Freestyle is more oriented towards takedowns and wrestling on the feet. In folkstyle thoguh, points can be gained while a wrestler is on top, or “riding”, his opponent.

“His top and bottom game were pretty good in high school, but going to the OTC and taking two years off, transferring styles from freestyle to folkstyle, I think he’s still getting adjusted to it,” said fellow ISU wrestler Drake Swarm. “Bottom and top are crucial to folkstyle. You ride a guy for a whole period that’s a point, you ride a guy for the whole period in freestyle, you get no points for riding anybody.”

Nickerson, an NCAA champion and four-time All-American at 125 pounds, has seen the potential in Hall, it’s just a matter of putting the right pieces of the puzzle together.

“This whole year has been a learning process and an adjustment phase for him,” Nickerson said. “…We haven’t quite seen that breakout performance yet that we know he’s capable of and a lot of that is attributed to that transition from freestyle to folkstyle. He has all the skill in the world and he’s beaten former world-team members, the best guys in our country. He’s got the skill, he’s just adjusting to that top and bottom wrestling.”

“You haven’t seen the real Earl Hall, yet”

The gray December sky provided a bleak and dreary backdrop to a bustling Ames, Iowa scene on Dec. 1, 2013, as hoards of wrestling fanatics from across the state piled in to to see Iowa take on Iowa State. Hall was slated against then No. 4-ranked Cory Clark, a freshman out of Pleasant Hill, Iowa.

Clark jumped to a quick 2-0 lead after a takedown, the only points of the first period. After choosing down to start the second and getting the escape to push his lead to 3-0, it looked as though his early control of the match would continue for the remainder of the match.

Hall hadn’t had his say yet.

Hawkeye and Cyclone fans alike shot to their feet, letting out both exuberant and excruciating bellows as Hall hit his patent cement mixer not once, but three times, nearly pinning Clark on all three. In the end, Hall’s pitfalls as a folkstyle wrestler were his demise.

He lost 8-7 on riding time.

After the dual, ISU coach Kevin Jackson sat in front of a league of reporters and said, “…You haven’t seen the real Earl Hall, yet.”

Some might have seen glimpses of the “real” Hall as he battled with Clark on that dreary December day, but to get a better look, the clock must be wound back to April 2012 at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Iowa City, as the 18-year old Hall stood across the mat from the giant of wrestling at the time: Henry Cejudo.

Cejudo was the reigning Olympic gold medalist at 55 kilograms, reaching the pinnacle of the sport at the age of 21.

Originally, Hall was not set to take on Cejudo in the first round, but found himself against the Olympic gold medalist after the weight was re-bracketed

“I thought to myself, ‘Man, they’re just sending me out here and don’t want me to win any matches,” Hall said.

Cejudo was the clear favorite to win the match, but just like Hall’s match with Clark, he had not had his say yet.

Hall, the starry-eyed, unknown teenager, took down one of the best wrestlers in the world.

“I scored, I wasn’t expecting to, honestly, but I scored,” Hall said.

Then, the match turned.

“I got kind of complacent, I just thought “I just got a takedown on Henry Cejudo”, but I tried to take him down right away and I wish I just would have took him down and locked up my turn and turned him, but we got into a little scramble and he came out on top and after that I didn’t do anything else,” Hall said.

Hall lost the bout in a 1-1, 5-3 decision. He didn’t stop there though.

After the loss to Cejudo, Hall won two matches in the consolation round, one of which was against Zach Sanders, a former Minnesota grappler and four-time All-American.

“He’s never afraid to go out there,” Nickerson said. “He’ll go out and he’ll take down Henry Cejudo, an Olympic champion, and he has beaten some of the best guys in the country and those kind of experiences, knowing that he can compete with the best, those are invaluable to our athletes.”

The 2012 U.S. Olympic trials live in wrestling folklore as the final outing for Henry Cejudo. After beating Hall, Cejudo went on to lose two matches, after which, he hurled his shoes into the crowd, a symbolic gesture of his retirement from the sport.

Two years ago in Iowa City, the spotlight above Cejudo faded, but just as that was happening, Hall’s light was starting to flicker on.