Inside Syria: One ISU student shares her experiences with Assad’s regime

By Mandy Kallemeyn/Iowa State Daily

An Iowa State student shares her story of what it’s like to deal with the Syrian conflict, even though she is more than 6,000 miles away.

September 20, 2013

Maha knows fear.

It’s what wakes her in the middle of the night and possesses her to check Facebook and go through the news. Then she tries to go back to sleep. For Maha, she described this as part of her daily routine for the past two years.

When Maha wakes in the middle of the night it is because she is worried about her family’s safety and trying to find out if their neighborhood was targeted in any recent attacks.

Maha is here as an ISU student, but her family is still back home, in Syria.

While she was growing up in Syria, her parents would never speak against the government out of fear. Openly criticizing the regime with friends was unthinkable, and even now as a student at Iowa State, more than 6,000 miles from her native nation, Maha is afraid.

Maha asked to have her name, year in school, area of study and even the last time she visited Syria remain unpublished. She fears that the regime would use such information to track down and persecute her family who remain in her home country.

“Parents can’t talk to their children about the government,” Maha said in a telephone interview with the Daily. “Nobody would dare to think about criticizing the government because you will just disappear. You can’t trust even friends, very close friends. People will tell.”

After speaking to the Daily on Friday, Sept. 13, Maha found out that her sister’s apartment in Syria was bombed. Luckily, her sister was not inside the building and was not harmed. There were reported injuries from the attack, but no deaths.

Maha said there are 17 different security agencies in Syria whose job it is to spy on anyone within the country.

She recalled that while growing up in Syria, there would be one or two “informers” from one of the security agencies in every school classroom.

“They just report on the students,” she said. “Who frowned when the president’s name was mentioned? Who did not clap loud enough when the president’s name was mentioned? Everything was forced. If you don’t do that, you’ll be punished.”

Even with the fears, however, Maha still felt it was important to speak out.

“If we don’t do anything, nothing will change,” she said. “If the people who are abroad don’t do anything to bring awareness to the people, especially the people in the United States, then the world will just continue watching. It will just be the usual two-minute reports [on the news].”

Maha said that what started as peaceful demonstrations two years ago was immediately met with extreme force by the Syrian government, led by President Bashar al-Assad.

The Emergency Law that had been in effect for several decades made it difficult for Syrians to gather and demonstrate, but that law was finally lifted in April 2011 as the demonstrations began, Maha said. The law placed heavy restrictions on travel and ability to gather throughout the country, and Syrians could be arrested when suspected of endangering the country’s security.

“Just for the people to come out and go for peaceful demonstration, it was really huge,” Maha said. “The regime reacted to these demonstrations with extreme force.”

A team of investigators sent from the United Nations confirmed in a report released Monday that chemical weapons had been used on civilians in Syria on Aug. 21.

In an address to the nation on Sept. 10, President Barack Obama asked the Congress to postpone a vote to retaliate militarily on Syria in order to pursue further diplomatic solutions. The diplomatic efforts with Russia and Syria ended with an agreement that Syria would give up its chemical weapons.

Maha does not believe that the current plan for Syria to give up their chemical weapons will solve the country’s problems.

“They’re getting into the regimes game, and the regime is really good at playing those games,” Maha said. “[The regime] are trying to prolong the process going into the negotiations. It is going to take years to destroy these weapons, if ever.”

Maha said that prolonged time will be used to continue killing the civilians of Syria.

“This is a country that is being destroyed completely by its president, and the people are being slaughtered by the regime. It’s been going on for years now, and nobody is doing anything,” said Maha, who explained that news reports on Syria are mild in comparison to what is actually taking place.

Maha said her family has been unable to reach a refugee camp, but if they could go, they would.

“They just live under the threats of shelling every day, but they have no other option,” she said. “The roads that connect Syrian cities are very dangerous, and there are checkpoints everywhere.

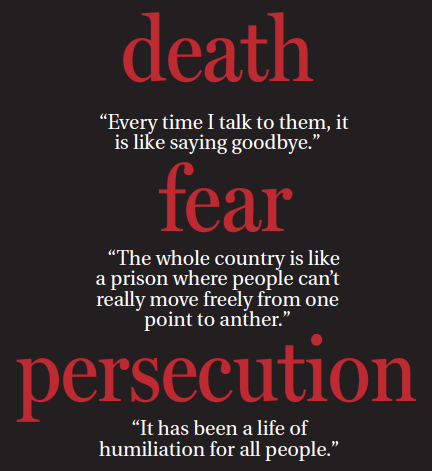

“The whole country is like a prison where people can’t really move freely from one point to anther.”

The U.N. has reported that more than 100,000 people have been killed in Syria during the last two years.

Maha knows where her family is and is able to speak with them whenever she can make a connection, but she remains concerned for their safety.

“Every time I talk to them, it is like saying goodbye,” said Maha, who explained that this thought used to be harder to deal with. “Now you kind of surrender and know that this is fate. You kind of push through it.”

Maha once planned to return to Syria but now is unsure. The Syria she said she hopes for is not what exists, and she does not see that changing anytime soon.

She is looking for a Syria where the people can be free and say what they want. She also wants to return to a Syria where the people are treated with respect by their government.

“We have never been respected by the regime or the people who work for the regime,” she said. “It has been a life of humiliation for all people.”

Right now, Maha said she just wants the killing to stop.

“The world should not wait for the regime to use chemical weapons to act. And even if the regime gave up the chemical weapons, they are still killing us.”

With Russia and China currently vetoing any resolutions for the conflict, Maha said finding a solution through the U.N. looks nearly impossible.

She would like to see countries around the world become more involved with intervention in the situation, but she explained that does not have to mean direct intervention.

“It’s going to take years after the regime has fallen for everything to be better. The thing to do now is to stop the killing.”