Belding: Doesn’t matter how they say it, it’s still a story to me

Column Battle 11/28

November 28, 2012

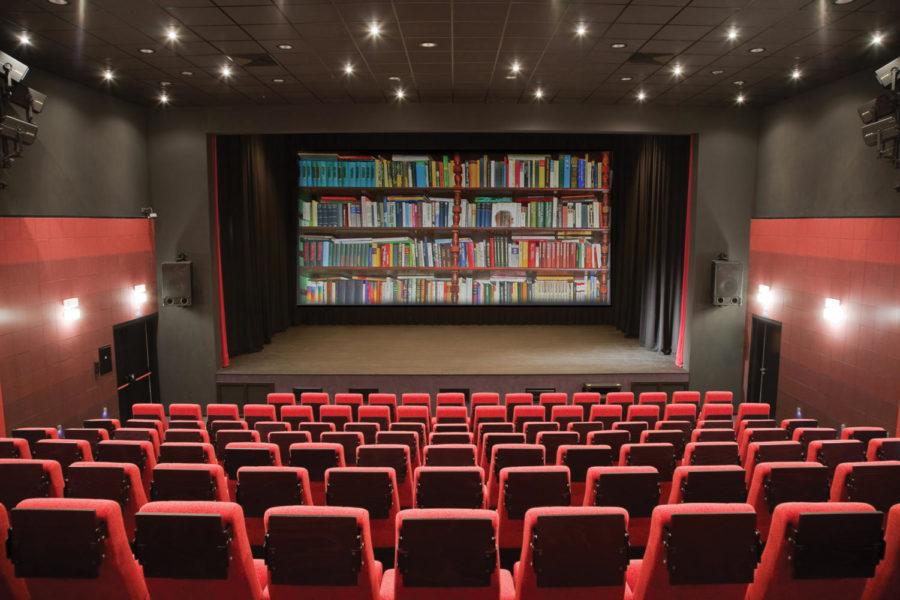

Wherever we go, there are books. Indeed we seem to have taken Thomas Jefferson’s declaration “I cannot live without books” to heart. They function as props, shields, antidotes to boredom, windows into far-off lands and times bygone, and many other functions as we carry them around train stations, airports, coffeehouses and, with the advent of the Kindle and its apps for iPads and smartphones, in our pockets.

We also carry them onto the silver screen of our movie theaters, the stages of our playhouses and the risers on which our choirs stand. Adaptations abound. A short glance at a moviegoer’s entertainment options, classic and current, show that authors of the printed word are one of the most abundant sources of stories.

Staples of American film culture such as “Gone With the Wind” and “The Wizard of Oz,” for example, are based on books. So are popular modern films such as “Sherlock Holmes” and the James Bond movies that have entertained millions of us for 50 years now — yes, even James Bond can count a book as his birthplace. Aside from plotless action flicks that consist of car chases, sex and shootings, most movies come from books.

But performing our favorite stories for an audience is not the province only of famous movie producers or artistic minds seeking to adapt an old classic to new times. All of us, in our own way, whether it be a puppet show for our parents with our stuffed animals, or a high school drama competition, put our own stamp on it.

Authors are only one kind of storyteller and, for all the millennia of human existence before we scratched around in wet clay and drew our communications in cuneiform chicken scratch, other methods kept precedence.

As long as humans have existed, they have been trying to communicate their tales and fables to more audiences, have been trying to reach other people in other places. Troupes of actors stored repertoires in their memories of the best stories, without respect to their physical source, for millennia. As we developed electricity and film technology, we began to capture plays for audiences that could watch a performance from any distance in time or space.

I am no fan of democracy but, nevertheless, I must credit Hollywood and giant publishers such as Macmillan, Penguin and Scribner’s. They do a good job of improving the overall literacy of our society by making all kinds of stories at all levels of literacy available to anyone who has enough money to buy them. Millions of people would not know the stories of such classics as “The Great Gatsby,” “Pride and Prejudice” or “Anna Karenina” were it not for the movie industry.

Although time limits and an audience’s lower level of common knowledge require script writers, directors and actors to abridge their performances, it is more than just replication of the original author’s original intent that creates a good movie or a good play. “Gone With the Wind” could have been ruined just as much through a poorly exposed film reel or a prop manager forgetting a glass of brandy as it could have been ruined through the professional negligence of Clark Gable or Vivien Leigh. Similarly, the experience of reading a book can turn from a sublime experience into an annoyance through a failure to proofread, bind the pages well or choose a typescript that conveys the ethos of the book in addition to being legible — or it can make that journey through a failure to develop the characters with a literary skill. The craft of storytelling and that of presentation exist in a symbiotic relationship. Without one, the other cannot survive.

We need not trouble ourselves that all the details of a great book do not appear in the movie adaptation. The book is the book, and the movie is the movie. Indeed, some versatility may even be desirable. One of the most successful writers of the Victorian era, Wilkie Collins, continuously remade novels serialized in magazines into bound novels into short stories into musicals into plays.

Unlike the classic movie “Citizen Kane,” most of us do not see in “deep focus,” where everything, at every distance, is clear. The medium is the message, it is said, and different venues allow producers — and audiences — to pick up on different parts of the puzzle.