Editorial: Land-grant colleges designed to foster civic virtue, not just research

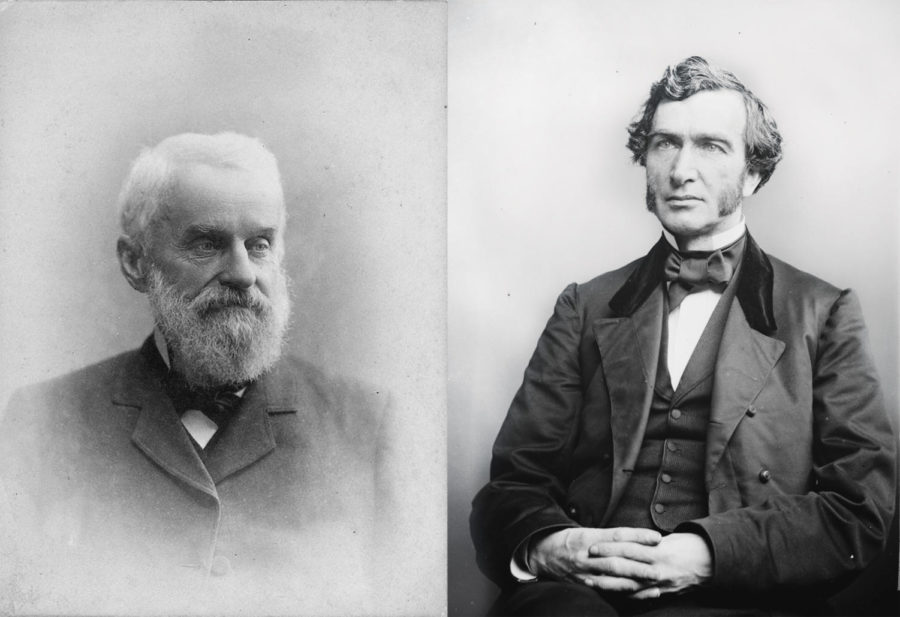

Photos courtesy of Flickr and Wikimedia

Opinion: Editorial 9/19

September 19, 2012

Once again, we take this editorial opportunity to discuss one of the many parts of the speech that Iowa State’s new president, Steven Leath, gave Friday at his installation ceremony. This time, we give attention to Leath’s comments about Iowa State’s first president, Adonijah Welch.

Leath noted Welch “was a bold visionary” who wanted to make the new land-grant colleges improve the lives of the state’s citizens in important ways. To educate students in a curriculum that would prepare them to do that, Leath said, Welch “made sure that the core programs of engineering and agriculture were balanced with the liberal arts and sciences, so students would be broadly educated.”

Without a doubt, he did so.

Having seen the portrait of Welch that hangs in the rotunda of Parks Library, we want to suggest there was something more subtle and intricate going on with his presidency. The determined focus in his expression suggests something more than just making sure students know a little knowledge about a lot of things.

As Iowa State’s first president, Welch was responsible for implementing the vision of U.S. Rep. Justin Morrill, for whom the Land-Grant College Act would be named. Truly, learning had no greater advocate in the 19th century than Morrill (and Leath also spoke about him on Friday).

Morrill was concerned about the industrial and agricultural wealth of this country. He saw the pace of development and cultivation lagging behind countries in Europe and noticed the United States was unable to provide for its own needs. To address that difference, he wanted states to charter “colleges for the benefit of agriculture and the mechanic arts.”

Morrill was also a Whig, however, and later a Republican. He feared the millions of poor Americans — who were uneducated in most areas, let alone public service, now able to vote because property requirements had been eliminated in the decades before the Civil War — would vote in their own interest rather than the interest of the American republic.

Universal male suffrage, Morrill said in 1876, could pose a real threat to the United States’ republican institutions: “Every one of our own citizens has been crowned with equal power in the guidance of national and State affairs; but they have thus far had too little of our aid to fit them even to guide themselves.”

That situation was lamentable, he observed, because republican and democratic political systems require education: “It is only a truism to assert that education is essential to our form of government. The best government must have the best men as citizens. A republic … falls even among races claiming to be enlightened. Democracy must fail when only upheld by ignorance and vice and can only succeed by a general diffusion of knowledge and virtue.”

In a word, Morrill feared demagoguery and populism.

Knowing institutions of higher learning had long been responsible for giving the more independently wealthy a “liberal” education — that is, an education that allowed one to transcend material wants and needs and act in the political interest of the community — Morrill grafted onto them the means by which common Americans could gain that education.

Morrill’s plan would solve both problems by giving Americans a publicly-oriented education as well as one by which they could improve the livelihoods of themselves and their communities. Morrill stated in 1872 the students of land-grant colleges “are to be taught a double duty; first in their characters as men and, second, their responsibility as citizens of the great republic.”

In both liberal and practical education, education was supposed to do real-world work.