Belding: Character education at least as important as technical training

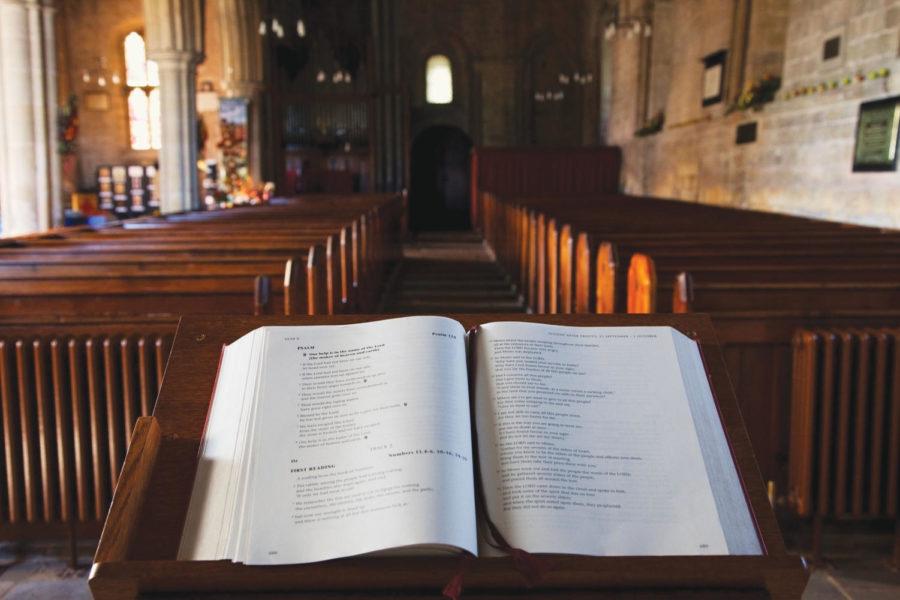

Open Bible at the front of a church

August 24, 2011

Despite my young age of 21 years, my friends — yes, dear reader, even I have friends — often chide me for being an old man. One friend insists that because I play backgammon, always wear dress socks and have prescription glasses of the bifocal variety I am actually 74 years old.

So maybe it is only my old soul shining through, but I cannot help but notice the cavalier, contemptuous disrespect and irreverence with which nearly everyone, but especially people my own age and younger, treats everyone else, living and dead alike.

My childhood, granted, was straight out of a story book or fairy tale compared with that of so many of my friends. It was also marked by an education in character and morals — an education, it seems, which has gone extinct.

The childhood activities I remember most are these:

- attendance at Wings, the Thursday-night Bible education program for children;

- religious attendance at church and Sunday school every week and Vacation Bible School for its week every summer;

- watching “The Waltons” one night each week with my mother and siblings;

- my mother reading to my siblings and me the “Little House on the Prairie” and “Chronicles of Narnia” books;

- and my guiltiest feelings occurring whenever my mother would catch me disobeying her or trapped in a lie I’d weaved.

Couple these with spending all my time at family functions with the adults because I have no cousins my own age, and one will learn a great deal of respect. The thing I remember most easily about the Little House books is that “children are to be seen and not heard.” Apparently the education was so thorough that until very recently people would ask me — just like clockwork, by the close of our second meeting — whether I’d gone to a Catholic school.

It should come as no surprise that so much of our population, especially that under age 40, battles alcoholism, drug addictions, unwanted pregnancy, bankruptcy and divorce when we were all given such license as children.

We see groups of teenagers flash-mobbing stores to steal whatever they want. Their numbers overwhelm the staff, and they have their way with the merchandise. Nor is protesting, such as those in Britain a few weeks ago, acceptable. Pouring into the streets, assaulting police officers and the people standing by, throwing rocks through store windows and destroying their part of town is not how civilized, educated people behave.

Simply getting children into the schoolroom, training them to have a job, isn’t enough. They must actually be trained in the way that they should go, rather than turned loose in the economy.

When the only expectation for children is that they will not disturb their parents’ pursuit of guilty pleasures — when we have no expectations for what our children will actually do, rather than what they will not do — why should we expect them to function well with other people once they reach high school and the years beyond that?

Training people to perform certain tasks might give them a paycheck and create some profit to grow the economy, but any properly built robotic droid could just as easily do the same. Indeed, dear reader, it may be better to use such machines, from a profit-making point of view. Machines do not think or feel emotions or bleed when wounded.

But it is our ability to work together and create shared experiences that has led, over the accumulation of all past millennia, to human civilization. And for that, moral education in the ways of interaction is necessary.