Letter: Insight into critical race theory

Intersectionality

March 13, 2019

While this is my first public letter, I thought I would offer some insight into critical race theory (CRT). I will follow up with a letter on intersectionality.

First, in the “Intersectionality, critical race theory serve as political ideologies” letter the author states that he does not “subscribe to intersectionality but rather to individuality.” This comment took me back to my Educational Sociology course where I read Dr. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (2014), who states, “individualism” has been used since the 1950s, but has now “been recast as justification for opposing policies to ameliorate racial inequality…” (p. 82). The author is using “individuality” to center his argument on himself, without regard to the lived experiences of thousands of other students on this campus.

Secondly, I’d like to touch on the author’s statement that, “Race is the most arbitrary and least important aspect of myself.” Although this may be the writer’s experience, centuries of history prove otherwise, with overwhelming evidence of inequality in public school access/funding, redlining, voter suppression, and disproportionately more people of color in prison – with only stereotypes/ideologies, not evidence that black and brown people are more violent, just to name a few. The sole premise of the book referenced by Bonilla-Silva is that, although race is a social construct, race still has a “real social reality” (p.8). Additionally, eminent critical race scholars, Ladson-Billings and Tate (1995) share that race is the central construct for understanding inequality (p. 50). Delgado & Stefancic (2017) also note that critical race theory provides the study and transformation of the “relationship among race, racism, and power” (p.3). Therefore, for those that do experience race in real ways, CRT provides research-based truth.

My third point is to provide a counter-narrative to the author’s comments on race and politics. The article states that “race functions as the foundation of political ideology.” The author seems to be using this as evidence that race is used as a political agenda by those who discuss race. However, I find it important to point out that race has systematically been used to control persons of color economically, politically and socially.

For my fourth point, while I could not tell if the author was making a case for organized religion, I can agree with the quote, “even more troubling is that for many more, these racial or intersectional political ideologies function more akin to a secular ‘religion.’” As I completed a masters of divinity degree from Emory University, I agree that the social statutes of race continue to serve as ideological truth and are left as critically unexamined as religious doctrine.

My fifth point is that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. did speak vehemently and directly about race relations and the violence committed against black Americans. Yet his words are often used as a troupe to provoke colorblind ideology, which is antithetical to his legacy. Furthermore, Delgado and Stefancic point out that critical race theory finds grounding in the works of “Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, W. E. B. Du Bois, César Chávez, [and Dr.] Martin Luther King, Jr.” (pp. 4-5).

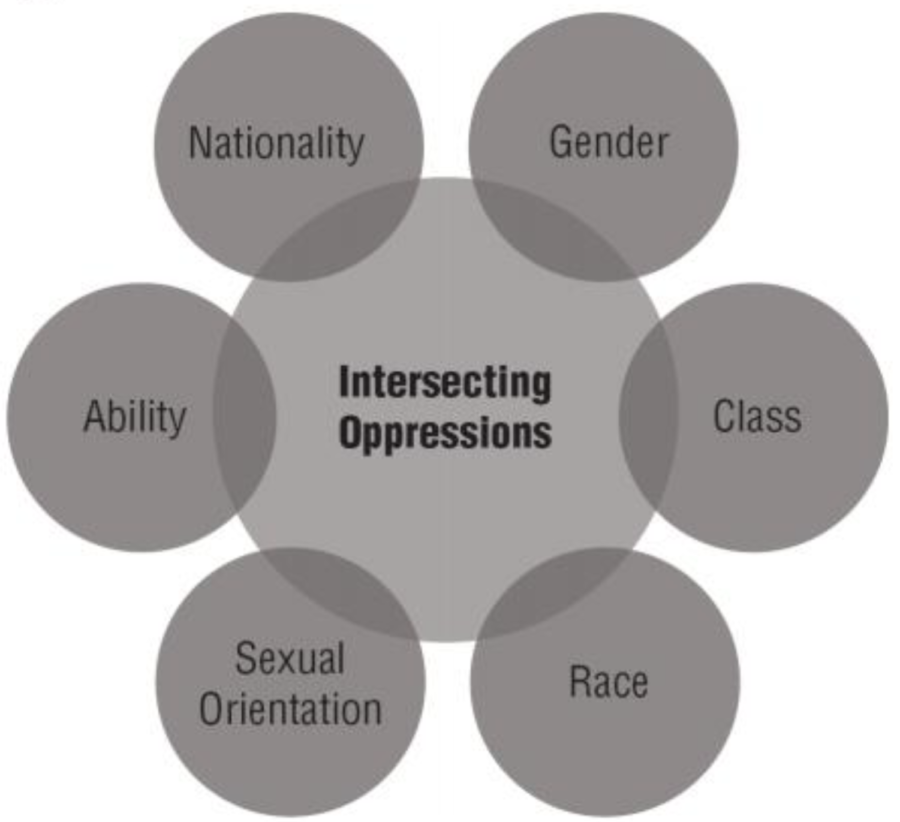

The author notes that “… if one probes deeper into intersectionality and race theory’s canon, you will see what any rational person may view its contents as actual racism.” This comment leads to my sixth point where I wonder if the author has, in fact, read items on intersectionality or critical race theory? Is the author stating that individuals are not discriminated against because of their intersecting identities of race, class, sex, religion, sexual identity, etc.? I would venture a guess that the answer to my first question is “no” based on the overgeneralized statements made.

With the author’s statements, “the root concept of DiAngelo’s ‘white solidarity’ that all whites hold views, perspectives and experiences that are all innately the same” and “the opposite of this is true as well, as people of color all must share views, perspectives and experiences that coincide,” he seeks to equate these experiences as the same when they are not. This introduces my seventh point, which is that the first part of the author’s claim is an example of how ideologies are ingrained, whereas the idea that all people of color should be seen as the same is called stereotyping.

My eighth point is that the use of critical race theory at a learning institution could only aid them in their goals towards inclusivity. The article notes that “A public university should not endorse any political or religious ideology as truth, but too often we allow intersectionality and critical race theory to be advocated and taught as clearly factual.” I would counter this statement by saying that if universities really want to take a deeper look at themselves and their interactions with people of color, that valuing truth in intersectionality and critical race theory – if dismantling systems of inequality is truly the goal – is a great place to start.

The ninth point deals with this idea of one truth being more relevant than another. The author writes, in response to a comment made at an event, “Your views, and DiAngelo’s, are not truth. Ideas formed through the racial lens are simply political ideologies, not moral authorities.” The author cannot discount the truth of another while writing about their own truth. Many people of color would love to think about race as arbitrary and the least important aspect of ourselves, but others’ ideologies, locked doors, crossed streets, blank stares, microaggressions and invisibility tactics do not make that our truth. Simply saying a racial lens is political does not erase the centuries of racialized harm.

As for the moral authority mentioned at the end of the original article, my tenth and final point would be to ask the author to consider, who sets this “moral authority?” History, philosophy, and theology tell us it is rooted in individuality, which by its nature does not consider the morality and agency of everyone.

And while everyone has their opinions, the over-generalizations made in the “Intersectionality, critical race theory serve as political ideologies” letter are harmful to those who do not share the author’s lived reality.