Guest Column: Social distancing is teaching Generation Z the limits of a virtual world

October 6, 2020

I thought in 2004 that social media would exhaust and divide us, making us uncivil and even hostile. Now I have hope for young people.

Social distancing, partisan politics and isolation may put an end to the culture of “Iowa nice.” But the emerging generation just might save it.

I have lived most of my life in the Midwest but came to know “Iowa nice” upon my arrival in 2003 at Iowa State University. Cellphones were in use then, but students mostly kept them in book bags and said hello to each other and professors on the campus green.

We agreed to disagree most of the time, even on hot-button topics. The Huffington Post blamed that tendency for slower advancement on progressive ideals that once were “the cornerstone of the state.”

There were plenty of sexist, racist, xenophobic and other offensive incidents that undercut belief in Iowa nice.

I experienced that in my Dec. 26, 2006, Register essay, titled “Let conscience guide debate on immigration,” noting how then-President Ronald Reagan viewed the matter. A reader clipped my commentary and penned profanity-laced warnings in the margins: “Why don’t you talk to the people who really know the cost of these rotten, stupid (profane slur) to us taxpayers.”

Do people still clip articles, write in margins, put stamps on letters and mail them? Or has technology made that too labor-intensive when we can tweet?

I believe, philosophically, in Iowa nice. We all have ordinary, public, worst and best selves. Our ordinary self, the one our friends and family see every day, may need a moral wake-up call now and then. Our public self, which we exhibit at work, may be opinionated but mostly kept in check. Our worst self includes road rage, hate and bias.

Our best self, rooted in the conscience, aspires to higher ideals with acts of kindness, forgiveness, gratitude, compassion, empathy and grace.

Technology has undermined that, too. I have tracked it for decades.

My 2004 book, “Interpersonal Divide: The Search for Community in a Technological Age,” (Oxford Univ. Press), cast doubt on claims of tech companies promising a near-utopian virtual future. We were supposed to work less and be more inclusive, informed and democratic.

That did not augur well for Iowa nice.

The 2017 second edition — “Interpersonal Divide in the Age of the Machine” — affirmed those early projections and predicted we would exchange moral values for machine ones.

All the while, I shared my research in several columns in the Register, advocating for social media regulation and explaining technology’s role in reporter arrests, fake news and politics. I even advised families during holidays to “hide the router.”

In “Twitter is a fountain of untruth and a test to Iowa’s culture of ‘nice,’” I noted how social media was ruining our rural legacy of helping others. Neighbors, I wrote, “were defined by their conscience, not by their political affiliation. It didn’t matter whether they were liberal or conservative, whether they voted for Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump.”

With digital diatribes about the 2020 election, that may no longer be the case.

Now factor in COVID-19. Technology has become a safe mechanism to ensure social distancing. We also fear each other. Half the population wears masks, the other half doesn’t. Even that has become political.

The Register reported in June that Democrats were twice as likely to wear a mask as Republicans. A new report shows 64 percent of Republicans are wearing masks. Among Democrats, 94 percent do.

Has coronavirus infected Iowa nice? Would you stop on a country road to help a stranger whose car slid into a ditch? Or would you overlook the well-being of others rather than be inconvenienced? Would fear of COVID-19 compel you to ignore the ditched vehicle and drive blithely on?

We might continue social distancing after an effective vaccine has been distributed and administered. We may trust each other less because of deep-seated fears and doubts about our neighbors.

There is hope.

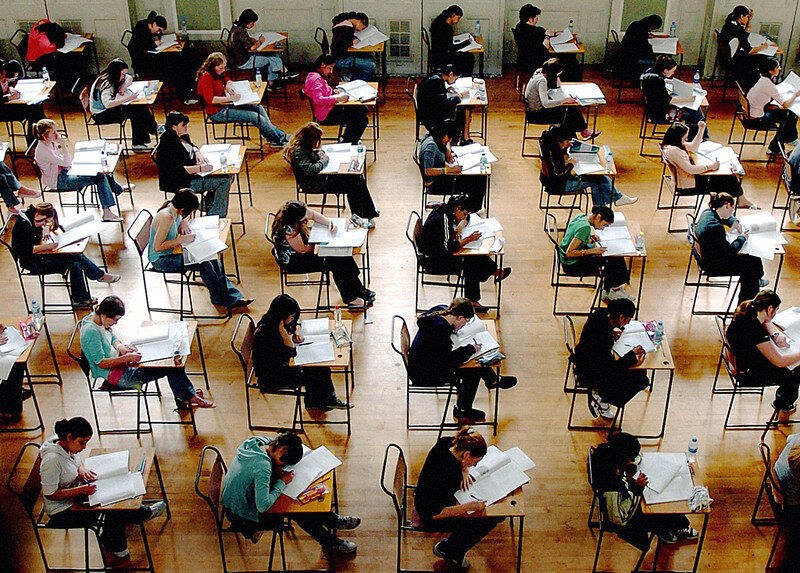

The future of Iowa nice depends on Generation Z, those party-happy high schoolers and college students whose world, prior to COVID-19, was defined to large extent by technology. In 2019, before the virus, they spent seven or more hours on it for entertainment alone without counting school and homework.

The great awakening within this demographic is the recognition about limits of the virtual world.

Because they were deprived, they will treasure face-to-face interaction. Why not? They reluctantly attended digital proms and virtual commencement. Now they long to slow-dance again and kiss strangers. They will play sports and cheer wildly in the stands. They will protest, pray and party without risking punishment. They will pay tuition at residential universities and actually meet their professors.

References to Zoom and WebEx will revolt them.

But they will stop their fuel-efficient sedans or gas-guzzling pickups at the side of the road and help ditched strangers, too, no matter color or creed.

Michael Bugeja is an author and distinguished professor at Iowa State University, who also writes regularly for the Des Moines Register and Iowa Capital Dispatch.