A rundown of redistricting in Iowa

September 30, 2021

As the redistricting process occurs across the country, Iowa and California remain the only states to allow independent committees to draw election boundaries.

Redistricting takes place every 10 years in line with the census. Those districts will determine which counties are within which congressional districts.

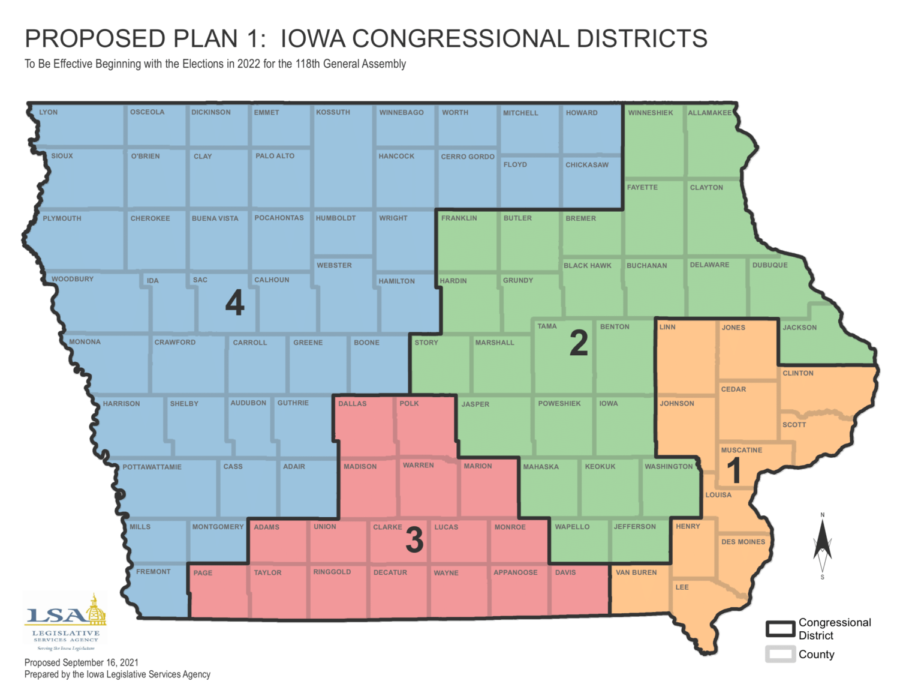

Under the proposed maps, Story county will switch from the 4th congressional district to the 2nd. The 1st, 2nd and 4th congressional districts remained the same in terms of registered voters, but the registered Republicans surpassed the Democrats in the second district. U.S. Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks, the Republican representing the 2nd district, won by six votes in 2020.

Independent Redistricting

In most states, the new district maps are drawn up and approved by the state legislature. In Iowa, the maps are drawn by the Legislative Services Agency (LSA), a non-partisan bureau that provides general research and legal services to the Iowa Legislature.

The maps are then sent to a five-person committee for approval. The committee attempts to remain neutral by having two members selected by the Republicans, two by the Democrats and the final member is then decided on by the other four.

After they pass the committee, the maps are sent to the state legislature to be voted on for final approval. If the legislature rejects them, there are two more chances for the maps to be approved. If they still do not pass, the redistricting will be left up to the legislature, but this has never happened.

Kelly Shaw, an associate teaching professor of political science at Iowa State, said that Iowa’s system is designed to not be partisan.

“Iowa usually is applauded for best practice in terms of that because it is viewed as bipartisan in the sense that the lines are not going to be redrawn for political purposes,” said Shaw.

COVID-19 Delays

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the results of the 2020 census were pushed back. Typically, the data for legislative and congressional districts are released by April, but COVID-19 caused data collection and verification issues. The data was released Aug. 8, four months late.

Since redistricting is reliant on the census data, the delay has caused problems there as well. With the new maps not yet approved, candidates for the upcoming legislative and congressional elections have been running on the old maps.

“Some people who have already announced that they will run have been, at least with this first map, maybe put into a district that they don’t want to run in, or they’re running against another individual from their party. So are they going to continue to run or not?” said Iowa state Rep. Beth Wessel-Kroeschell, (D-45).

If the new maps are approved, more than 40 percent of legislators would be in a district with another incumbent. Wessel-Kroeschell said that she had not seen any formal announcement of how this will be addressed.

The Iowa legislature will hold a special session Oct. 5 to vote on the proposed maps.

Gerrymandering

A consequence of the traditional form of redistricting is gerrymandering, which is the manipulation of electoral district boundaries to establish an advantage for a particular party group or protect an incumbent.

Malapportionment involves creating voting districts with equal representation but unequal populations. This devalues the votes of those in the larger district by giving the smaller district a higher ratio of population to influence. Typically, this results in rural areas having more representation than urban areas.

Iowa’s process avoids this through its attempts to remain unbiased as well as having rules as to how the maps can be drawn. All districts must cover an equal population, and political variables cannot influence boundaries. They also have to be contiguous, and counties cannot be divided, which prevents demographics from being split up and weakened.

“If you don’t have these guidelines to follow and you’re purely partisan, you could really diminish a core of minority voters,” said Shaw, “If you wanted to be nefarious, you could split that county in half and put half of the minorities with the west suburbs and the other half with the east suburbs and in essence then you could make their vote in the center not count for anything.”