Biden’s infrastructure plan faces a tough political road

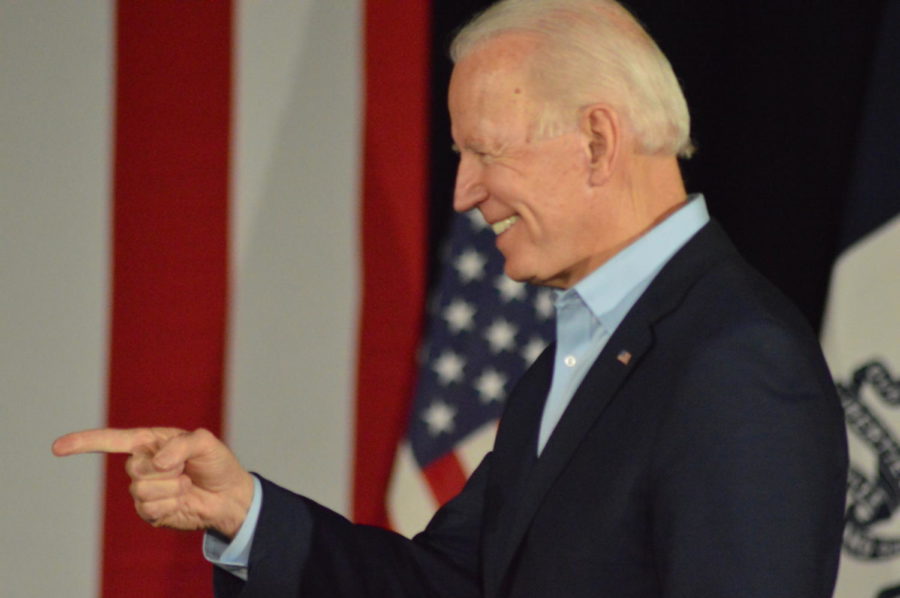

Joe Biden has run for president a total of three times, his first time being in 1988 and second in 2008.

April 6, 2021

President Joe Biden’s infrastructure-focused American Jobs Plan, unveiled March 31, has been met with mixed reactions across the political spectrum and will likely face political obstacles to its passage.

The plan calls for $2.3 trillion of government investments in areas ranging from repairing roads and bridges, expanding broadband and modernizing transportation infrastructure to enhancing home care for the elderly and greening the electrical grid. The spending would largely be financed by corporate tax increases and, to a lesser extent, government borrowing.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-KY, has already signaled that Biden’s proposal will not be getting support from the GOP, saying in a press conference in Kentucky that he intends to fight Democrats every step of the way.

“It’s the wrong prescription for America,” McConnell told reporters. He called the bill a “Trojan horse” calling itself infrastructure but disguising tax increases and more government debt.

Biden has already received national criticism for the scope of the plan from the progressive left of his own party, notably from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-NY, who has championed a climate-focused plan commonly referred to as the “Green New Deal.”

In a tweet, Ocasio-Cortez said the plan’s call from $2.3 trillion over 10 years “is not nearly enough” and told MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow that what is really needed is closer to $10 trillion over 10 years.

Iowa’s congressional delegates, as well as students involved in politically affiliated student organizations, also expressed a range of reactions to Biden’s plan.

Rep. Randy Feenstra, a Republican representing Iowa’s fourth congressional district, which includes Ames, emphasized the role infrastructure plays for Iowa’s agriculture industry but expressed concern over the portion of the proposal earmarked for things beyond the “traditional” definition of infrastructure.

“After I saw Biden’s plan, 9 percent of it is infrastructure … the rest is minutia,” Feenstra said, echoing a frequent conservative talking point that some fact checkers have called into question. “I’m hoping he will reach across the aisle and we can work together … and have some give and take, unlike the last COVID bill.”

Feenstra said he’s willing to talk about what’s needed and in what amounts, reiterating that supporting infrastructure is the path to supporting agriculture.

Chuck Klapatauskas, a junior in mechanical engineering and president of Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative-leaning student organization, also expressed concern both at the cost and how the plan would be financed.

“I love the idea of additional infrastructure, but that funding cannot be from simply extending the debt ceiling,” Klapatauskas said in an email. “I think the only logical way to source revenue is by slushing [sic] other funds.”

Klapatauskas also expressed concern about the corporate tax increase, saying he worried that an increase from the current 21 percent rate to the proposed 28 percent rate could hurt the U.S.’s global competitiveness and incentivize manufacturing and research to move out of the country.

For students on the other side of the political spectrum, the proposal represents a step in the right direction.

“My first reaction was hopeful,” said Raj Oberoi, senior in management information systems and the political director for the Iowa State College Democrats. “It’s a considerable amount, obviously, but this can be a good first step before we reevaluate.”

Oberoi also referenced the corporate tax increase but acknowledged that even the proposed 28 percent rate is lower than the 35 percent tax rate under former President Barack Obama.

“The economy was doing fine then, so I think a lot of the concerns about the spending are not really going to be a big deal in actuality, and economically, we’ll be fine,” Oberoi said.

Rep. Cindy Axne, a Democrat representing Iowa’s third congressional district and the sole Democrat in Iowa’s congressional delegation, said in an email that she is fully supportive of making infrastructure Congress’ next priority.

“Getting our economy back on track, strengthening our workforce and our working families and growing new opportunities for those out of work and those just entering the job market all rely on having a foundation that supports those goals,” Axne said, “and that starts with having the infrastructure we need to be competitive.”

Axne expressed an interest in bipartisanship as well, specifying that she wants to see a package passed that reflects the “wide range of priorities necessary” to get the economy recovering and growing, as well as investing in the future of Iowa.

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, D-CA, has said she wants to see Biden’s infrastructure plan passed into law by the Fourth of July. Analysts, however, see that as unlikely, both due to the likely legislation’s complexity and the political obstacles it will face.

“Anything this big is going to be difficult to pass through Congress, even under the best of conditions, which this is not,” said Mack Shelley, chair of the political science department at Iowa State. “At this point, I’m inclined to say both yes and no [that it has a chance of passing].”

Currently, Democrats have a slim majority in the House, inviting potential obstacles from the party’s progressive wing, led by representatives such as Ocasio-Cortez, in addition to opposition by Republicans who think the plan goes too far. Democrats’ control of the Senate is even slimmer, holding fifty seats along with Republicans, and maintaining their majority only by the ability of Vice President Kamala Harris to cast a tie-breaking vote.

This razor-thin majority presents yet another hazard for Biden, as losing the support of even one Democratic senator could derail the entire infrastructure package.

“The Democrats would have to keep all of their people on board,” Shelley said, “including, critically, Joe Manchin from West Virginia.”

Manchin is recognized as the most conservative member of the Senate Democratic caucus, and with the necessity of keeping every vote to pass legislation, the West Virginia senator is in the position to be effectively able to veto any large legislation, Shelley says.

As an illustration of the sway Manchin holds in the Senate, one must only look to the most recent COVID relief package. Although the Senate Parliamentarian technically sank the $15 per hour minimum wage passed in the House, it was Machin’s opposition to the policy that kept Democrats from taking the procedural steps that could have saved it.

Barring the unlikely proposition of at least 10 Senate Republicans defecting, and even with Manchin on board, Democrats’ ability to pass any legislation relies on procedural, sometimes arcane, measures.

The first is the filibuster. Most commonly understood as “talking out a bill,” the filibuster is a way of blocking the end of a debate on a bill, the parliamentary mechanism that allows it to move forward to a vote. Historically, senators would have to object to ending debate and then speak on the floor for the duration of their filibuster, as Rand Paul did for 13 hours in 2013 to block an executive nomination, which can only be ended by a vote of at least 60 members.

The filibuster changed in the 1970s, when Senate rules were changed to allow other business to continue while a filibuster of a bill occurred. Now, a senator only has to state that they object to moving forward with legislation but does not have to speak about their reasons. This blocks a bill without stopping other Senate business, but it still requires a 60-vote supermajority to overcome.

The filibuster has been changed in the past, notably to end the practice for judicial and eventually Supreme Court nominees, and Democrats’ bare majority after the 2020 election brought the question of ending it back into popular consciousness. The COVID relief package and Biden’s infrastructure plan have made the question even more urgent.

Shelley, however, does not see it as likely that Democrats will completely end the filibuster, especially given the influence of Manchin and Krysten Sinema, another conservative Democrat representing Arizona, although further modification is a possibility.

“It is possible that Manchin could be OK with transforming the current filibuster [back] into a talking filibuster,” Shelley said.

Shelley speculated that one potential alternative that could garner support could be a filibuster with a legislatively set amount of time for any senator opposing a bill to speak, with the filibuster automatically expiring when all who wished to speak had exhausted their time.

If Democrats leave the filibuster in place as is and Republicans follow through on McConnell’s pledge not to support Biden’s plan, Shelley says Democrats will be left only with a process called budget reconciliation.

Budget reconciliation was created in 1974 by the Congressional Budget Act and allows the Senate to pass laws that change policy on spending and taxes while keeping the national budget in line. Unlike other legislation, reconciliation bills are not subject to the filibuster and can be passed by a simple majority, making them an attractive option if one party has a slim majority.

Since its passage, the Budget Act has been interpreted as saying that Congress could only pass one reconciliation bill per fiscal year. Democrats have already used the procedure in passing the most recent COVID relief and stimulus package, meaning Senate rules would prohibit them from using the maneuver to pass Biden’s infrastructure plan.

“It looks like Democrats would have to wait until fall to be able to use reconciliation for the new initiative,” Shelley said. The federal government’s fiscal year runs October through September.

However, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-NY, released a statement Monday stating the Senate Parliamentarian agrees with his novel interpretation of the Budget Act, which would allow Democrats, through some still-more complex procedural maneuvers, to use reconciliation a second time, opening a path for party-line passage of Biden’s infrastructure plan.

Ultimately, Biden’s infrastructure bill is likely to prove to be a drawn-out legislative fight that will play out on a timescale of months rather than weeks. The struggle between Democrats and Republicans over infrastructure, Shelley said, will have a lot to do with the politics of the “working class” and which party will be able to gain the attention of blue-collar workers.

“Biden was introduced by a union leader,” Shelley pointed out. “A large part of that sales pitch is the Democrats trying to eat away at the working-class base that Trump had built up. … We’ll see if that works.”