Lecture: How archaeology killed biblical history

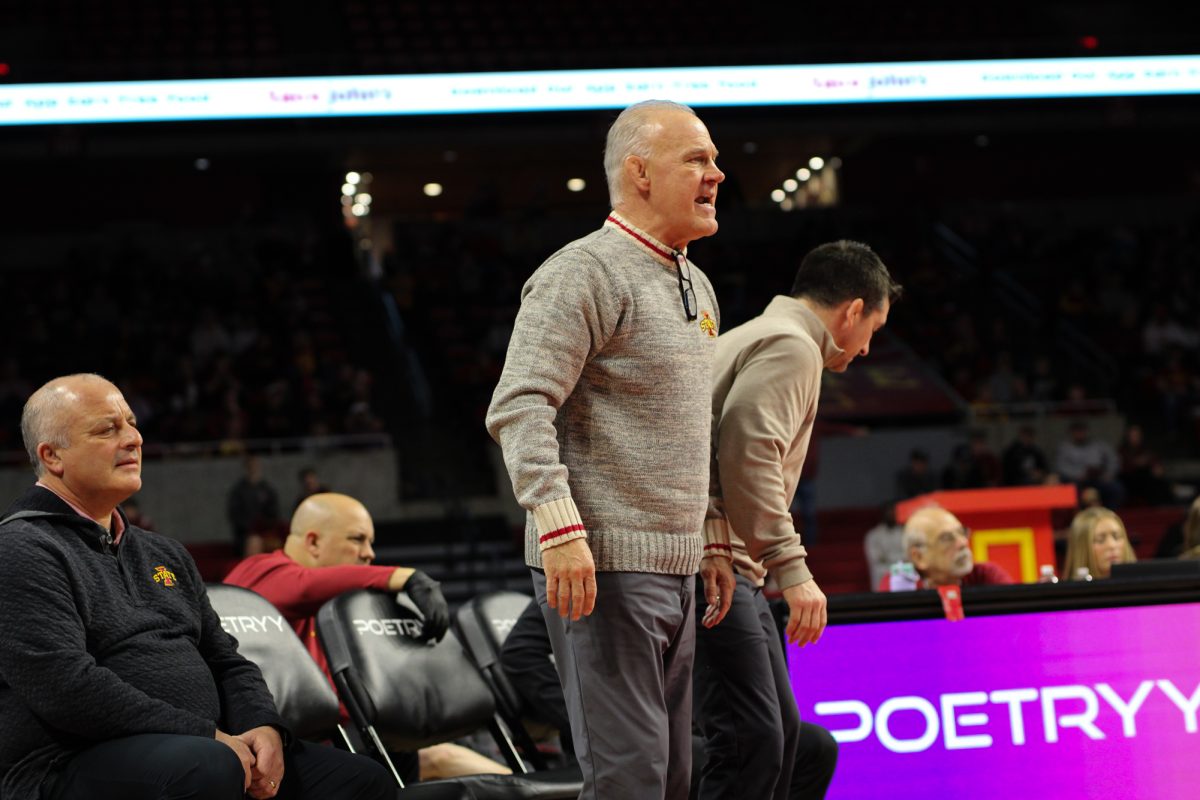

Megan Petzold/Iowa State Daily

Hector Avalos, professor of religious studies, speaks during his lecture “How Archaeology Killed Biblical History” in the Campanile room of the Memorial Union on Oct. 16.

October 16, 2018

Using the information provided by buried treasures from the past, the answers we once thought to be true regarding the Bible’s historical accuracy may not be so after all.

Hector Avalos, a professor of religious studies, presented intriguing insight relating to the Bible’s events versus archaeological finds Monday at 6:30 p.m in the Memorial Union Campanile Room.

“The bible is a product of cultures whose values, beliefs, [origin, nature] and purpose of our world are no longer held to be relevant by most Christians and Jews…the bible [is] irrelevant,” Avalos said.

Avalos quoted the 2005 Gallop Poll, “fewer than half of Americans can name the first book of the Bible.”

Avalos additionally referenced the 2006 Baylor University study, explaining how a large percentage of Christians never read scripture, “…how is the Bible relevant if a third of Catholic don’t read scripture, if 21 percent of Protestants don’t read scripture.”

Referencing Dr. Michael Coogan, Avalos noted how even Christians are unsure of its accuracy or relevance. Comparing 1900 to 2018, Avalos claimed Genesis, among many other parts of the Bible, are no longer found to have relevance or importance in the historical narrative.

William G. Dever, however, does “fight for what little is left” of the historical context, Avalos said.

“We have 39 books…Dever only regards a small portion of those texts to be relevant,” Avalos said.

What led this change in relevancy? Avalos says the rise of science, the rise of university trained biblical scholars and new discoveries in the East have eliminated what was previously thought true.

The Amarna Letters, discovered in the late 1800s, “show no trace of any Israelite entity” that are discussed in Exodus. The Stele of Merneptah, the earliest mention of Israel as a history, did not even conclude what exactly Israel should be considered, a territory or a people.

“One of the things about Archaeology in the past is about trying the find Solomon the building,” Avalos said.

Referencing William G. Dever once more, Avalos said how three similar gates were indeed found, but with differences from what was exactly portrayed in the Bible.

“Here is a rare dramatic instance of archaeology turning up actual structures mentioned specifically in the Bible,” Avalos said.

Avalos also pointed to other areas of biblical history which archaeology is starting to impact.

“There are no proven remains of buildings ascribed to David or Solomon,” Avalos said.

Also figuring into this are mason marks, included on a palace built in the 9th century. Avalos said these do not hold true with Solomon’s attributed time period.

“How can they be from the 10th century if they’re very similar to those from the 9th,” Avalos said.

Another structure was the Tel Dan Stele — discovered around 1994 — which references subjects about David.

“But it’s not from David’s time,” Avalos said. “It’s from the 9th century…It’s possible that this is evidence that there wasn’t David.”

Major differences are present in the different versions of the Bible, a certain problem claimed Avalos.

Finally, looking at Jesus, Avalos said, “Jesus was a failed revolutionary. There is no new data about Jesus from Jesus’ time.”

The earliest evidence is P52 — the earliest manuscript of the New Testament — Avalos said. However, these were written many years after Jesus’ time, leading to a gap that in people’s knowledge. This gap is an immensely large difference of approximately 90 years.

“…less than 1% of the Bible can be independently corroborated historically or archaeologically,” Avalos said concluding the lecture.