In 2016, then-presidential candidate Donald Trump announced his intentions to “open up our libel laws,” so when legacy media outlets like The New York Times or The Washington Post “write purposely negative and horrible and false articles,” the subjects of these alleged “hit pieces” could sue the writers and “win lots of money.”

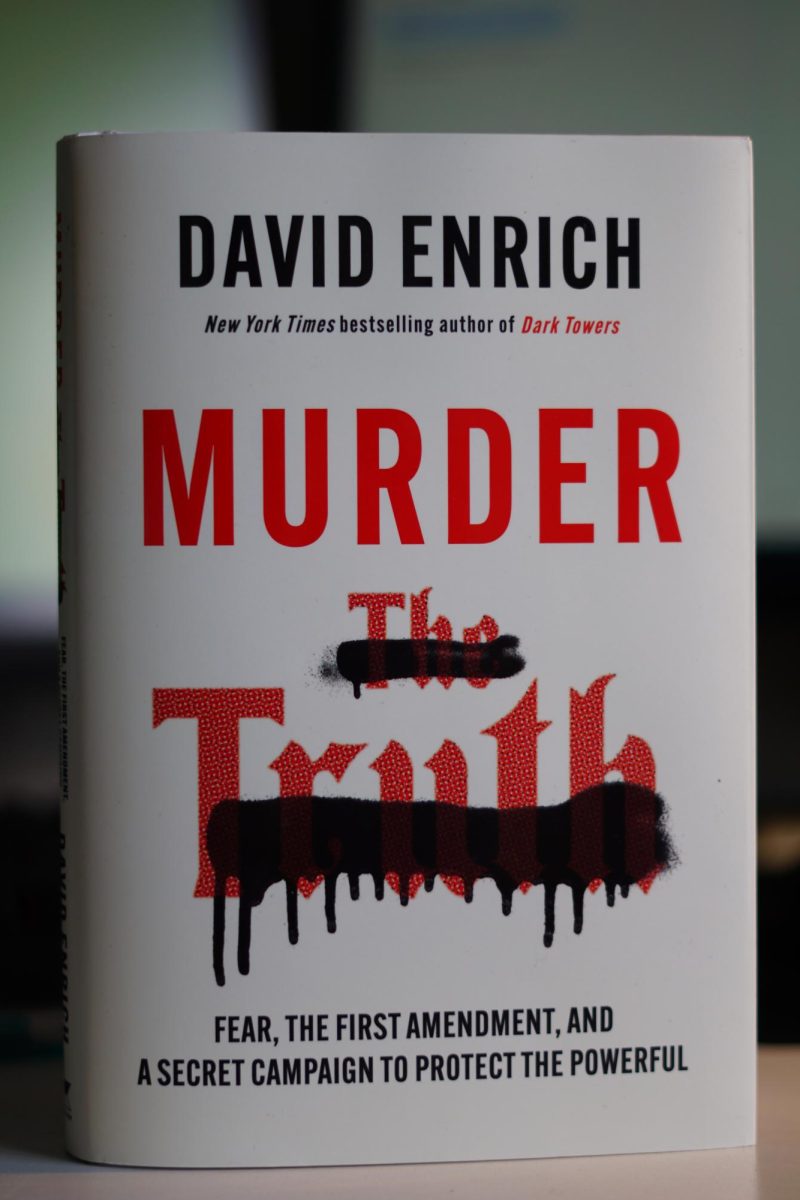

Since rising to the top of the American political scene a decade ago, Trump has likely had more words published about him than any other human in the modern world. Naturally — from his words to his mannerisms — he is a polarizing figure. It is not surprising, then, that Trump shares the common loathing among elites for a free and effective press since the existence of such institutions threaten the privacy of unsavory information. When Trump vows to screw the lid off libel laws, it is simply a euphemism. David Enrich, the business investigations editor for The New York Times, demonstrates in his new book “Murder the Truth: Fear, the First Amendment, and a Secret Campaign to Protect the Powerful,” that underlying Trump’s promises is a vast and powerful political/legal network that intends to undermine our basic press and speech freedoms to insulate themselves from honest criticism.

The book concerns the 1964 New York Times v. Sullivan Supreme Court decision and provides comprehensive case studies that not only describe the deliberate and aggressive attempts by wealthy and powerful people to silence their critics but also why they target the Sullivan precedent to do it. Supreme Court Justice William Brennan writes in the Court’s unanimous opinion on Sullivan that press organizations can only be held accountable if plaintiffs demonstrate that the information in question was published with “reckless disregard” for the truth and constituted “actual malice.”

This standard is critical for protecting journalists investigating powerful public figures, allowing them to work and publish their findings without fear of political and/or legal retribution. Enrich writes that the “theory” of the Supreme Court regarding Sullivan “was that a vigorous, probing press was an essential safeguard of democracy” and the “key to holding the government and other institutions in check.” However, as Enrich also points out, the freedom to tell the truth is under attack by those who attempt to weaponize “the obscure field of libel law” to curtail the protections afforded to us by the First Amendment.

Iowa seems to be a frequent host of these kinds of cases. In the book, Enrich describes how a libel case against the Carroll Times Herald and an Iowa State alumni effectively precipitated the paper’s ruin. Even though a judge ruled that the Times Herald reported accurately, the paper struggled to make ends meet after incurring hefty legal costs. More recently, Trump sued The Des Moines Register for “brazen election interference” because of a pre-election poll by Ann Selzer that showed Kamala Harris with a narrow three-point lead over Trump in Iowa (Trump ended up winning Iowa by 13 points on election night). And though the latter is not a libel case, it demonstrates how the sitting president is willing to target the media for something that he sees as unfavorable.

Other contemporaneous examples include Trump’s lawsuit against ABC, where anchor George Stephanopoulos inaccurately claimed that Trump was found civilly liable for rape instead of sexual abuse due to the narrower definition of rape in New York law. Trump has also repeatedly attacked and sued CBS, notably for a 60-minute interview with Harris which Trump described as “deceitful” because of edits that Trump argued helped “doctor” her answers. However, Trump lacks merit here (Enrich told me the case is “garbage”). CBS has supplied the original transcripts of the interview to the FCC and proved that it was engaged in “normal” (albeit controversial) editing. Some argue that ABC had good reasons to settle with Trump, but the crux of the issue is not whether or not that is true; rather, making mistakes and reporting minor inaccuracies is what Sullivan protects. If this were not the case, making an unintended mistake would potentially end careers, not only of journalists but of entire media organizations.

More than that, the legal movement in support of overturning Sullivan has gained traction in recent years. After Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas — a frequent target of media coverage — called for the Court to reconsider Sullivan in 2019 (followed by Justice Neil Gorsuch in 2021), there is now the worry that a conservative-majority Supreme Court could overturn Sullivan, which would amount to an alarming erosion of press freedom. That circumstance seems unlikely for now, but Enrich describes how when a network of important lawyers and judges issue opinions (like those belonging to Thomas and Gorsuch), it creates “self-sustaining echo chambers” that can, in the long term, bring devastating circumstances.

Of course, it is not difficult to see how the powerful, wealthy and well-connected are wielding this power to shield themselves from a pesky media environment. A shocking takeaway from this story is that many of these cases are not even designed to win on merit. If the rich can force the silencing of the media through relentless legal and financial pressure, that is good enough for them.

Thus, the small and independent news outlets (like the Iowa State Daily) are most vulnerable. In my interview with Enrich, he explained that legacy media organizations like The New York Times have large budgets and excellent lawyers that help them repel threats of intimidation. He demonstrates in vivid detail how small publications simply lack the financial and legal resources to put up a fight.

The book also dedicates many pages to refuting and deconstructing the arguments of those who favor overturning Sullivan. After reading, I was left with the impression that Enrich offered a clear and fair account of a highly vague and opaque area of law and illuminated why America needs profound realization; a class consciousness moment aimed at protecting our uniquely American sentiments and history toward free speech and press protections. The beautiful thing about the First Amendment is that it protects everyone, and the same individuals and organizations who challenge Sullivan are the same ones to seek refuge under its protections.

We do not need to look far for an example. One is the defamation case brought against Fox News by Dominion Voting Systems. Fox News agreed to pay Dominion close to $800 million to avoid a trial that, according to the Associated Press, “would have exposed how the network promoted lies about the 2020 presidential election.” But the interesting thing about the case is that the same lawyers that represented Dominion — Tom Clare and Libby Locke — were the same ones in favor of overturning Sullivan. Now, with their victory for Dominion, they proved that Sullivan worked. The case demonstrated that if a media publication knowingly distributed falsehoods (as Fox News had about Dominion), they could be held accountable. What is the lesson? Protect Sullivan.

I recommend this book to every American. Enrich’s writing is clear, incisive, and critical to understanding the role and security of free speech in America. It is a testament to the role of free journalism and a reminder that we cannot let the powerful try and murder the truth.

Buy it and read it. While you still can.

If you would like to watch my interview with Enrich about this book, it is linked here on my Substack.