Gradwohl celebrates 50 years of ISU Archaeological Lab

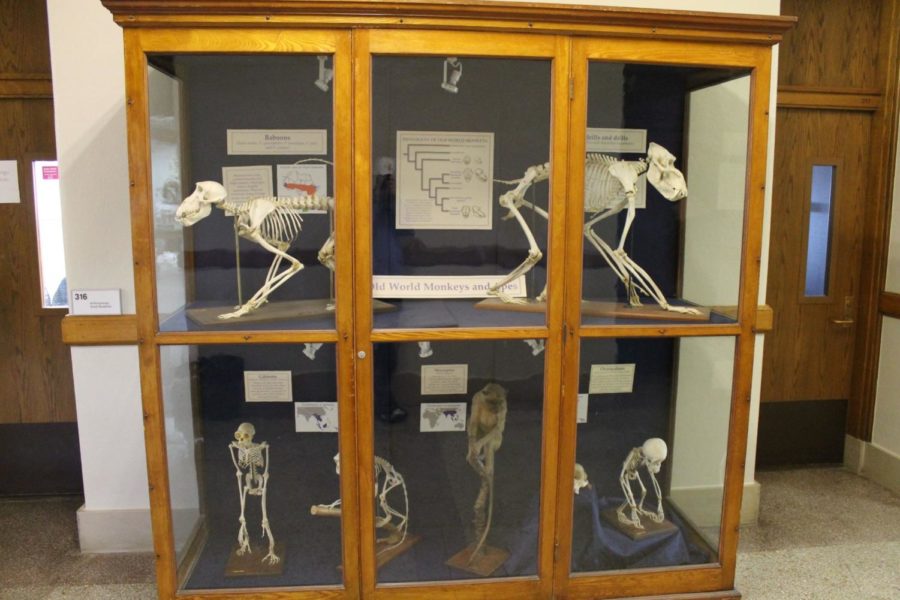

A cabinet filled with modern primate bones and information about each animal is on display in Curtiss Hall. The display cabinet can be found on the third level near the Department of Anthropology on Oct. 28.

October 30, 2014

Field school wasn’t exactly ideal, students had to live without running water and electricity for weeks. Not to mention working in the hot sun or rain during the days. It never stopped David Gradwohl from digging for artifacts.

Gradwohl, professor emeritus of anthropology and founding director of ISU Archeological lab, was described as absolutely relentless by his early students.

This year, the ISU Archeological Lab celebrates it’s 50 years of existence —if Gradwohl had not found a passion in digging for artifacts, the lab might not have been started.

About Gradwohl

“I attended the University of Nebraska, starting out as a freshman I had no idea what I wanted to do,” Gradwohl said.

It was the summer after his freshman year when he had found his passion. Gradwohl went with a couple of buddies to do fieldwork in South Dakota.

“We would live in a tent camp all summer without running water and without electricity,” Gradwohl said.

It was his the first time working at a field site. They explored prehistoric and early historic Native Americans who had once lived along the Missouri River. South Dakota State Historical Society was excavating the area before it was flooded by a reservoir.

“I went from $1.375 an hour in union wages to $0.75 an hour and living in a tent camp without electricity and running water,” Gradwohl said. “But gee it was fun.”

After his freshman summer Gradwohl took classes in anthropology and geology. Not only was the subject material interesting to him, but the instructors were passionate about the subjects they taught.

“I always had an interest in rocks, minerals and fossils even as a kid,” Gradwohl said.

After graduating, Gradwohl studied in Edinburgh, Scotland where he studied prehistoric archeology of Europe for a year. Upon returning to the U.S., he decided to pursue a degree in anthropology with a specialization in North American and European archeology at Harvard University.

It was around this time when Gradwohl and his wife were interested in settling back into the midwest for family and to pursue Gradwohl’s interest in plains archeology. Coincidentally there was a position open at Iowa State for a full-time anthropologist.

Gradwohl Begins at Iowa State

Gradwohl was working to complete his Ph.D when he was hired at Iowa State, but his dissertation wasn’t quite finished. Today, he wouldn’t have been able to get a job with an incomplete dissertation.

Social science was blossoming in the 1960s. There were more jobs than qualified people to fill them, Gradwohl said. He was the first anthropologist hired to teach anthropology full-time at Iowa State.

“I would never have the courage or naivete to do that again,” Gradwohl said.

There was a lot of interest in social sciences and new courses had to be created. For Gradwohl, it was exciting to develop and create courses in the anthropology program.

“It was the time in which President Robert Parks took over and he tried to install a program called ‘the New Humanism,” Gradwohl said. “It brought in new humanities and arts into what had been a university of agriculture, engineering and home economics.”

Developing Classes

Gradwohl said that often times professors with Ph.Ds weren’t required to take teacher certification classes. As a new instructor he tried to emulate professors he found effective when attending class.

“The participatory aspect, I intentionally tried to incorporate,” Gradwohl said, “After we got the archeology program established, I introduced participatory labs in the archeology and physical anthropology classes.”

In lab, Gradwohl’s students were tasked with making stone artifacts and pottery to help understand the authentic artifacts they studied. In the biological anthropology labs, students learned to identify bones and guess at the human’s cause of death.

He also had two-day field trips to archeological field sites. To this day, Gradwohl’s former students thank him for taking them on his popular two-day field trips.

“They remember having fun, they may also remember getting rained and snowed on,” Gradwohl said, “But the thing they enjoyed was the process of trying to discover data and finding answers to questions.”

ISU Archeological Lab

Before Gradwohl had left Harvard he had been contacted by a man in the National Parks Service congratulating Gradwohl on the position at Iowa State and letting him know of funding for salvage archeology in Red Rock Reservoir along the Des Moines River.

Iowa State and the National Parks Service paired up to fund research along the Des Moines River in conjunction with the ISU Summer Field School in Archeology for the summer of 1964.

“There was nothing, we had no shovels, no trowels, no shaker screens, no nothing,” Gradwohl said.

He had the money to requisition the tools from a store but was questioned why a sociology teacher would need shovels, luckily they were able to get the tools as well as a beat up truck to use.

After heading to the field, Gradwohl realized he needed space to store all the tools and artifacts collected. Luckily, the Dean of the College of Sciences and Humanities, Chalmer Roy, understood the need for lab space.

The ISU Archeological lab was given temporary space in the World War II barracks between Beardshear and Pearson until they received permanent space in the basement of East Hall.

During the first summer in 1964 Gradwohl took 13 students, three of which were women as well as two wives and a couple of children.

“The women were good workers, they were as good or better than the men,” Gradwohl said.

During that summer they stayed in an abandoned farmhouse without electricity. The boys and girls had separate dorms spaces.

The crew worked in the fields, excavating sites during the day and listening to Gradwohl lecture at night.

Gradwohl had a different approach to field school — women were allowed to work and were expected to work as much as the men, earning Gradwohl the reputation of being absolutely relentless. During that time women were rare in field schools in anthropology/archeology.

A Former Student’s Perspective

Nancy Osborn Johnsen, administer academic advisor and adjunct instructor for anthropology, was a student of Gradwohls’ in his early days of teaching.

“The first day we were digging with shovels and it started to rain, I thought ‘Oh, good we can go home,’ and no we didn’t go home,” Osborn Johnsen said, “We stayed in an abandoned farmhouse in the dark.”

After working in the field, Osborn Johnsen was hooked. She switched her major from history to anthropology.

In the summer of 1966, she was running low on money for college and decided to spend the rest of it on summer field school.

“I thought, ‘Well, if I don’t get to go to anymore college, then at least I will have had this experience,” Osborn Johnson said.

During her time at field school her parents told her she received a scholarship from Iowa State, so she would be able to continue college. She was then hired to work in the lab and went on to be a teacher’s assistant, a field assistant and ran the lab for about 13.5 years.

“It was great training ground for anyone who got to go there,” Osborn Johnsen said, “It’s a really good place for people to get socialized and learn about archeology.”

Despite working in the field under the hot sun and through rainy weather, many students enjoyed learning from Gradwohl and still keep in contact with him today.

Gradwohl estimates that he keeps in contact with 100-200 past students. Many of his students went on to be state archeologists, tribal preservation officers and a number work at national parks.

Gradwohl retired in 1994, after which there have been two more directors of the ISU archeological lab. Gradwohl lives in Ames and enjoys the perks of being retired.