You don’t know Jack: Uncovering the history of Jack Trice

Jack Trice came to Iowa State to play football but only played once. Though he later died from injuries he received in that game, his story is forever tied to Ames’ football stadium.

June 6, 2013

Jackie Robinson will always be known as the man who broke the color barrier. He almost single-handedly ended segregation in 1947 for professional baseball, becoming an icon across all sports. He is also remembered by his number, 42.

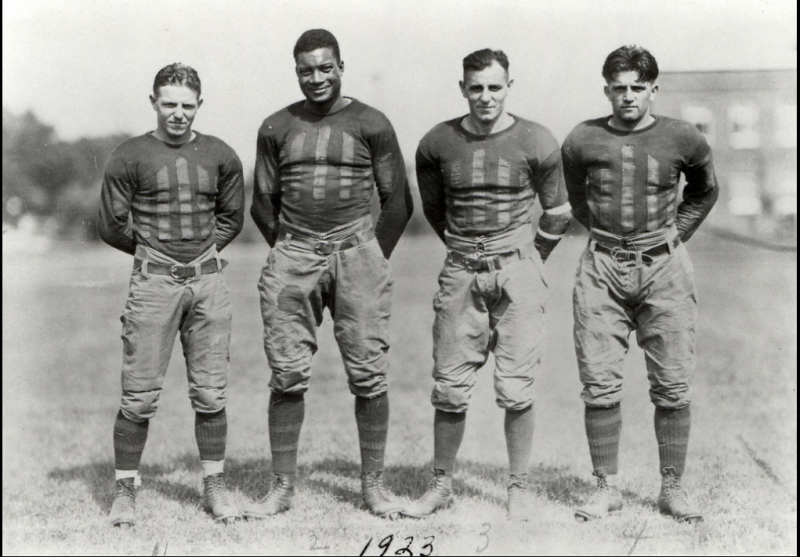

Rewind about a quarter of a century before Robinson’s time, when John “Jack” Trice became the first African-American athlete at Iowa State. In a time when black players, like Trice, had to stay in a different hotel than his white teammates, Trice would tragically become the first Cyclone athlete to die of injuries sustained during competition.

The Cyclone legend now has a stadium named after him and a statue erected right outside the stadium in his honor. With such a short career and little documented information on Trice, Iowa State alumnus Joshua Wagner sought out to find a missing piece of Jack Trice history.

“When I was looking into [Trice’s] story, I couldn’t help but notice that ISU hadn’t figured out his number conclusively, which bothered me,” Wagner said. “I felt if we were to properly honor Jack’s story, we should know his number.”

For Wagner, an Ames native and younger brother of former walk-on wide receiver Adam Wagner, the Cyclone influence was introduced early on in life. However, a more personal connection drew Wagner to Trice’s story and the search for the number.

“I’ve always been drawn to Jack’s story of struggling to achieve greatness in the face of massive adversity,” Wagner said. “Since I was born deaf, I have also had a lifetime of being told that I can’t do something, so I thrive on upsetting conventional societial norms.”

Since no official effort had been made to find Trice’s number, Wagner decided to take matters into his own hands. He sourced yearbooks, newspapers and any clippings he could to find a lead. Months passed and no picture or roster connected the iconic Cyclone to a number.

In 1999, Steven Jones, a Trice historian of sorts and author of “Football’s Fallen Hero: The Jack Trice Story,” had found a Minnesota newspaper clipping from 1923 with No. 37 listed as Trice’s number, but with multiple mistakes throughout the paper and no regulation of football numbers at the time, the single source was shaky.

That was until Wagner contacted Cyd Dyer at Simpson College. Dyer, Simpson’s librarian and archivist of 35 years, skipped searching the yearbooks and newspapers of the time and went with her gut.

“I just happened to say, ‘Where would I be if I was a Jack Trice number?’,” Dyer said. “I looked in our football archives box … and we happened to have an original copy of the football program from September 29, 1923.”

The program was a rare find from an often overlooked scrimmage against Simpson’s football team only nine days before Trice’s death. It took Dyer only 5 minutes to find the missing piece Wagner had been painstakingly looking for.

In the program next to “Trice, J.” was the number ’37’ and the confirmation Wagner needed to publish the discovery to his blog.

“To the best of my knowledge, this was the first time a primary source with Jack’s number has been found,” Wagner said. “I’m just glad I was able to bring a tiny bit of insight to Jack’s life and confirm his jersey number of No. 37. I believe with Steven’s newspaper source and this newly discovered game program, we can settle the issue.”

Now that Trice’s number has been confirmed, Wagner hopes the university recognizes the discovery and honors the local legend that is Jack Trice.

“Since ISU has a sparse football history compared to other schools, I think it would be great if ISU retired his number or chose someone — such as a captain — to wear it every year,” Wagner said. “I’m sure the ISU athletic department will recognize his number somehow [now] that it has been confirmed.”

However, Wagner isn’t stopping at jersey numbers. He plans to release a Jack Trice collection this fall on his website, Kagavi.com, that will include an in-depth story of Trice as well as a product “that people can use as a launching point to telling the story of Jack.”

Kagavi, a “storytelling company” inspired by his charismatic late grandfather, was formed by Wagner and his wife in 2012. The name is formed from “Kaga”, meaning “chronicler” and “Avi”, meaning “grandfather”.

In addition to the Jack Trice Collection, Kagavi has released a retro ISU basketball shirt that “could’ve been handed out at the opening game of Hilton in 1971.” Also to be released June 10 is a story and shirt telling the story of the 1957 Cyclone baseball team.

“All of our stories this year are going to be ISU-based and we definitely have more ideas for future years,” Wagner said of Kagavi. “We are never going to be a company that sells 100 different items. Each object is carefully considered, tells a story and is limited edition.”

The company thrives on being made in America, eco-friendly and giving back. At least 10 percent of all profits are donated to charities such as Make-A-Wish Foundation, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and Against Malaria Foundation.

As for Jack Trice and Cyclone athletics, Wagner hopes his company, however small the impact is, can bring people together and share the stories of Cyclones past and present.

“I have more plans later this summer and fall to share more of my other ISU research on more media platforms beyond Kagavi.com and I really want to foster a sense of interest and pride in ISU history.”