Glawe: The rise of the ‘political scientists’

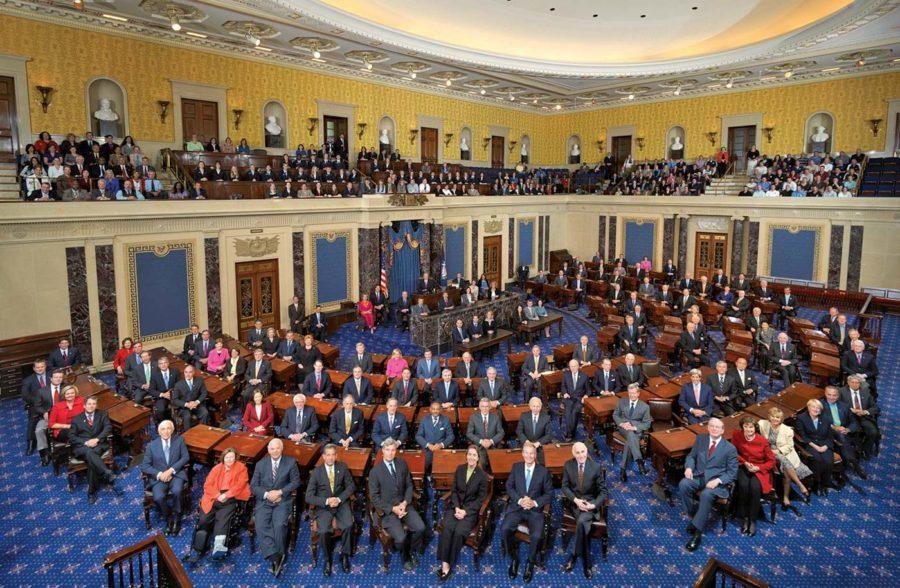

Photo courtesy of U.S. Senate/Wikimedia Commons

The partisanship in Congress needs to address big issues by taking them piece by piece. Lack of agreement has created a Congress that lacks debate.

March 1, 2013

Reports have recently been leaking out of the White House on the nominees for the directors of the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Energy. President Obama intends to nominate long-time environmental regulator Gina McCarthy to head the EPA and nuclear physicist Ernest Moniz to the Department of Energy.

With Republican lawmakers believing the EPA has harmed the economy with its rulemaking, and the intense opposition to the president’s most recent nominee Chuck Hagel, one can only imagine the gauntlet these two nominees will face when they appear before the Senate for approval.

My first thought on the nomination of a nuclear physicist was “Good. We need more scientists in politics,” but, now that I think about it, that might not be a good idea after all.

The need to inject scientists into government entities, especially into Congress, for objective evidence to be utilized to affect political change, is unfortunate. Politicians should already understand this, but their track record when pursuing unbiased evidence doesn’t show it.

Though I personally believe Republicans are severely misguided on the issues of climate change, evolution, etc., the politicization of science itself is potentially fatal for its objectivity. According to an extensive Pew Research Poll performed in 2009, only 6 percent of scientists openly declare themselves Republican while 55 percent declare themselves Democrats.

This shouldn’t matter though, right? Even if scientists out their political leanings, their research certainly won’t reflect their bias (at least, we should hope not). The scientific community and the scientific method will ensure this. The problem lies in the trust a hyperpolarized public has in the credibility of scientific research.

Mr. Moniz, with his tenure as head of the department of physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and as the under secretary of the Department of Energy, is more than qualified for the position. But I fear that the Republican Party will begin to connect scientists to the liberal ideology. When that happens, any hopes of drawing upon experimental evidence as a means by which we can come to formulate our policies are lost.

Bill Foster, a Democrat recently elected to be the House representative from the 11th District of Illinois, is also a particle physicist who has an ambition to reshape the political landscape. He believes that we need more scientists in government to force a connection between quantitative pursuits and political considerations.

Rep. Foster also intends to lend his expertise to the future decision-making on the budgets of science-oriented programs (such as those of NASA and other entities), another reason why he believes we need more scientists in Congress. His advocacy may be crucial to preserving funding for research. It will be interesting to see how Mr. Foster argues his points against an opponent that is becoming increasingly distant from the scientific community.

Foster joins the ranks of numerous scientists who have fought vehemently on the state and national level against legislation attempting to usurp scientific consensus by inserting pseudo-science into the classroom. It is certainly possible that the rise of scientists in the public sphere is warranted. Defending the integrity of our educational system is a civic duty.

I am deeply conflicted over the surge of the “political scientists.” On one end, we may have the chance to build up our human capital by investing in science-oriented disciplines. On the other end, an inherently unbiased entity becomes biased (in the eyes of the opposition).

In Latin, science (“scientia”) means “knowledge.” The term itself has come to encompass an organization of truth-seeking individuals. Even more, science is a process by which we seek to understand the world around us. When constructing a hypothesis, a scientist doesn’t pull a claim out of the abyss and decide to test its validity. Instead, a hypothesis, the proposed explanation of some natural phenomenon, is based on our observations.

The ensuing experiments provide us with the information necessary to explain our environment.

Shouldn’t we all embrace this pursuit? It is our duty, as beings with the capacity to “know,” to pursue the truth. As acting citizens, we should commit ourselves to what Socrates devoted his life to. Like Socrates, we can wake up every day, unsatiated, knowing that we can never know enough. That is the spirit of science.

If the channel through which we seek the truth becomes enveloped by ideology, then our desire to find scientific consensus will end in failure. We will no longer address our limitations with objectivity, but with subjectivity.

If the partisan bickering in Washington, D.C. were to adopt objective reasoning, we would certainly have no real need for the “political scientists” in Congress. Alas, only the future will tell us if science has managed to “tame savageness of man.”

——————————————————————————————-

Michael Glawe is a junior in mathematics and economics from New Ulm, Minnesota.