Editorial: Corporate collaboration endangers ISU’s land-grant responsibilities

June 7, 2012

As one inheritor of the land-grant legacy, it is imperative that the leaders of Iowa State University of Science and Technology remember our educational mission: to teach both the practical arts, such as agriculture and engineering, as well as the classical arts, such as politics, history and literature, in order to achieve the ultimate goal of making whole the character of the individual. Today, however, we are confronted with an insidious and pernicious dichotomy that arises from too much collaboration between the a university and its corporate partners and results in the contamination of both worlds.

As stated in the Morrill Act of 1862, the responsibility of land-grant institutions such as Iowa State is to educate students in “agriculture and the mechanic arts.” Iowa State has done much to uphold that responsibility. More than 150 years after its founding, Iowa State still educates nearly half of its students in agriculture, engineering and hard sciences and employs just under half its faculty in those areas.

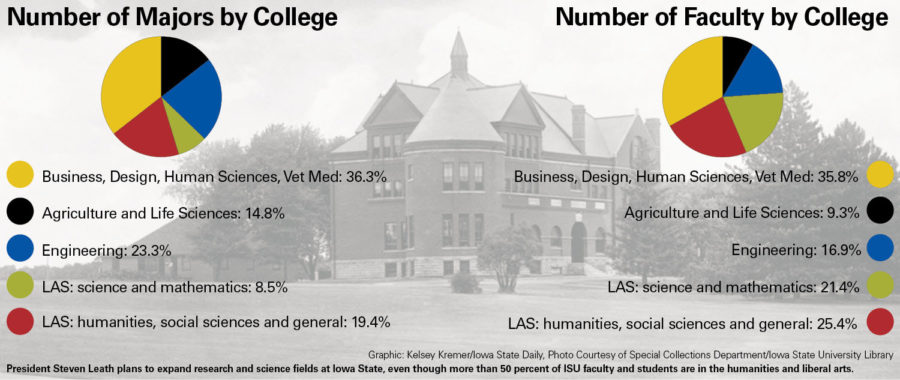

The College of Agriculture and Life Sciences employs 9.3 percent of faculty and has 14.8 percent of majors; the College of Engineering accounts for 16.9 percent of faculty and 23.3 percent of majors; and the science and mathematics division of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences employs 21.4 percent of faculty and educates 8.5 percent of majors.

By contrast, the “softer” sciences (the Colleges of Business, Design, and Human Sciences, and the humanities, social sciences and general divisions of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences) employ 52.3 percent of faculty and account for 53.5 percent of majors.

As colleges and universities whose “leading object” are “to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts,” land-grant institutions are supposed to do so “without excluding other scientific and classical studies.” At the heart of this matter is the prospect of failing to maintain the responsibility of universities, such as Iowa State, to serve the national interest by independently investigating scientific solutions to the problems of the day, in addition to maintaining classical standards of education.

In keeping with teaching “such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts,” President Steven Leath, according to two reports in the Des Moines Register and another in the Business Record, is eager to get involved with Capital Crossroads, a Des Moines association of businesses, to build a research corridor between Des Moines and Ames in the vein of North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park.

According to the Business Record, “Leath’s vision includes utilizing the university’s skilled labor force and its access to technology to help existing businesses and create new ones,” which it should.

The efforts to do so raise many of the issues involved with land-grant institutions. The devil of the matter lies in the close associations that would be built between Iowa State and the companies involved in the corridor.

The “constant dialogue with Des Moines business leaders in order to understand the business community’s needs” Leath wants is important, but answering “scientific questions [companies] don’t want to spend the time or staff to answer” would endanger our commitment to an educational balance between classical learning and practical learning.

Leath explained new-faculty expansion in the next few years (to the tune of 200 members) would be “organized hires, cluster hires, so we can really make an impact” in such fields as biotechnology, agricultural technology, metals, communications and others. One way Leath plans to finance those faculty positions is through private companies and grants.

We should avoid assuming the guise of the research and development wings of major for-profit corporations, yet Leath’s ambitions signal a shift from the fundamental beliefs of Justin Morrill. The sponsor of the original land-grant act believed people are the agents of change and colleges exist for the sake of people — both its students and its outside communities. Leath’s plans imply he believes the way forward for our university is working with corporations whose collaboration is motivated by profit potential.

Solving contemporary agricultural and industrial economic problems of the day was one of the aims of the Morrill Act. But as a public institution, we also have a public responsibility to pursue civilizational progress for its own sake, without regard to money making. We cannot risk shirking or neglecting our educational mission to all fields for the sake of corporate sponsorships and being able to bill ourselves as an important job creator.

We cannot forget that Education, in all disciplines, regardless of how profitable or popular the subject — from Russian literature to forestry to materials engineering and everything else — is the great object and reason for Iowa State’s existence. Our university was founded on the belief that practical and classical educations could be combined in a union under one institution.

We cannot now, 150 years later, construct a false dichotomy between technical training and scholasticism that undermines the unity of our academic role as a university and therefore fails to ensure that we deliver a whole, complete education.