Cyclone wrestling celebrates silver anniversary of gold performance

March 6, 2012

Kevin Jackson just didn’t get it.

The three-time placewinner for Louisiana State was exploring his options while deciding where to transfer — after the school’s wrestling program had been dropped — with one question persisting in his mind: Why hasn’t anyone been able to beat Iowa?

“I witnessed [Iowa] winning NCAA titles and dominating opponents,” said Jackson, who is now the third-year coach at Iowa State. “I had always competed well against Iowa opponents, but I did not understand why other programs did not compete well against Iowa.

“I felt like [they] bowed down, in a sense, to the black-and-gold singlet and to their style of wrestling and I wanted to go to a team that wasn’t going to bow down.”

Jackson transferred to Iowa State and redshirted the 1985-86 season, when Iowa won its ninth straight national title. Heading into Jackson’s final season of eligibility, Iowa was poised to make it 10 straight and build to an already storied legacy for the program.

A year later, Jackson did his part in ending the streak by placing second at the 1987 NCAA Championships in College Park, Md., where Iowa State spoiled its rival’s plans by winning the national title.

“It’s probably one that haunted me for a long time,” said Dan Gable, who coached the Hawkeyes from 1976-97. “We had a good run, but it ended at a time when I had my most talented athletes and that’s what’s kind of unique.”

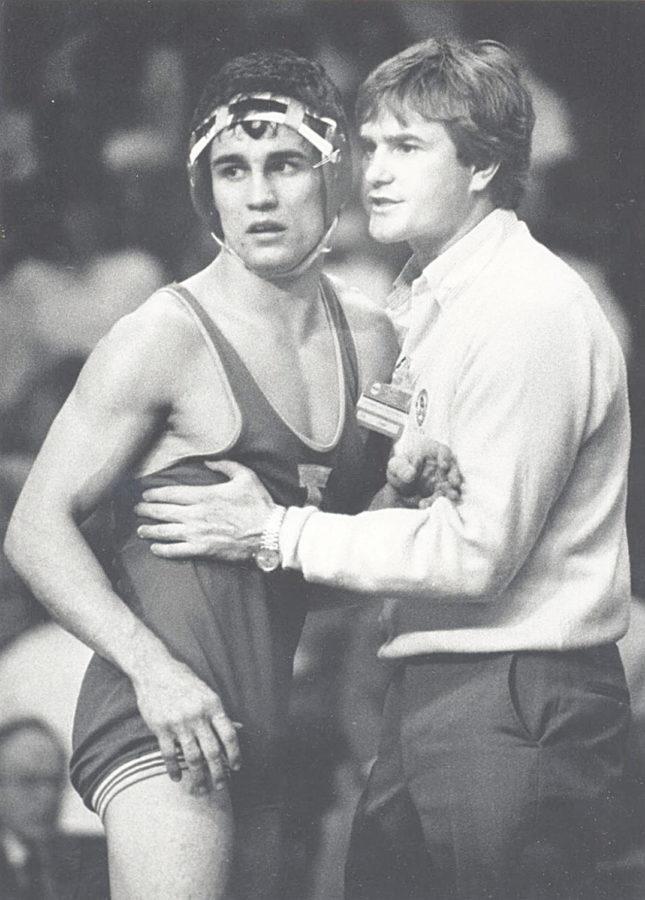

This year marks the 25-year anniversary since the “unique” turn of events surrounding Iowa State’s last national championship in wrestling, but the memories still resonate with former ISU coach Jim Gibbons.

“We kept our focus; we didn’t wrestle very many bad matches in the whole tournament,” said Gibbons, who coached ISU wrestling from 1986-92. “[Our team was] really mature about the way they handled the workouts and training. They did everything we asked them to do and the result was that they performed well individually in the tournament.”

Gibbons said even though the Hawkeyes were riding a nine-year streak of winning a national title, the pressure was placed more heavily on the contenders who sought to upend them.

However, the ultimate goal for Iowa State was not solely to beat Iowa and end the streak.

“You generally don’t train to beat somebody else, you generally train to beat everybody,” said Tim Krieger, who won the 150-pound title that year for Iowa State. “You go to the national tournament as a team, you go to the national tournament as an individual expecting to beat everybody.

“So just the fact that it came down to us and Iowa, I mean, it’s fun and it’s great for the state and it was a little motivation, but that’s not the point of it.”

Krieger upset Iowa’s Jim Heffernan, the defending 150-pound champion, in the third of five championship bouts that featured a Cyclone wrestler. Krieger would go on to win another 150-pound championship in 1989 and is just one of just 11 four-time All-Americans in ISU history.

The second championship bout to feature a Cyclone — in a session that saw its matches altered to accommodate live television broadcasting — was the 126-pound match, which pitted Iowa State’s Bill Kelly against Iowa’s Brad Penrith, another defending champion.

Kelly, who took the mat after Jackson’s 10-4 loss to Iowa’s Royce Alger in the 167-pound final, was trailing into the final minute of the third period before locking his leg with Penrith’s during a scramble to get him into a cradle.

From there, Kelly pinned Penrith to seal the title for the Cyclones and end Iowa’s streak.

“That was the signature moment that everybody remembers because we needed to win one out of those five matches to clinch the victory,” Gibbons said of the pin.

The moment of ending the streak was fulfilling for those involved, including Ed Banach, who won three national titles for Iowa and helped contribute to building the streak for seven of those nine years.

Banach served as an assistant coach under Gibbons after leaving Iowa, playing an instrumental role in helping prepare the team for the 1987 tournament after — what Gibbons described as — a meltdown the previous year.

“I found out where they were strong, found out where they were weak, made sure their weaknesses weren’t glaring where it was going to be detrimental to their success and really focused on helping them becoming a better wrestler overall so they did that,” Banach said.

“It was fun and rewarding to see them when a situation like that did arise, they were ready for it and it was fun to watch them meet with success.”

Gable said despite having one of his most talented teams ever, the Hawkeyes’ downfall came from an imbalance in emphasis between talent and work ethic.

“We were depending totally more on talent than work ethic,” Gable said. “I’m not blaming anybody except myself. The reason why I say that is because I wasn’t in control of the program or myself and I was letting winning, I was letting success determine just how much lack of discipline that was going on.”

It was because of this — along with the immensely honed focus of Gibbons’ Cyclones — that the streak did not continue.

Gable is famous for his disdain for losing, but made an exception for Iowa State.

“If I’m going to lose to somebody, that’s who I would want to lose to,” Gable said of his alma mater. “But I don’t want to lose to anybody.”