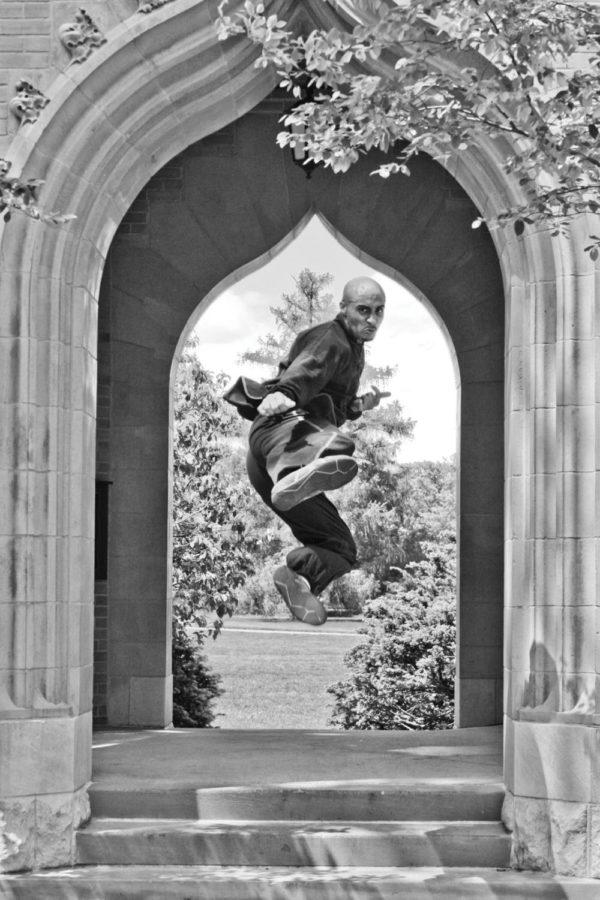

Kung Fu master looks to start club

June 1, 2011

The Cyclone Martial Arts Club held its first summer practices last month. Though the club offers instruction in several different martial arts, the Chinese martial art known as Kung Fu isn’t one of them. One ISU student hopes to change that.

Anthony Wharton, junior in kinesiology and health, has been studying Kung Fu for more than a decade. In that time, he’s attained the rank of Sifu (a title meaning “tutor” in Mandarin), qualifying him to teach the art to others. Wharton is eager to give students the benefit of his expertise. He wants to start an official Kung Fu club by the beginning of the fall 2011 semester. But before he can, he has to clear several bureaucratic obstacles.

Wharton said he has spoken with Department of Public Safety officials about the possibility of training outdoors with traditional Chinese weapons. He hasn’t gotten their sanction yet. He also said that he isn’t sure if the way he plans to use weapons flouts the Office of Risk Management’s regulations. Until he’s more familiar with campus policies, he wants to err on the side of caution.

“You can’t just bring a broadsword on campus and say, ‘This is how you swing it,'” Wharton said.

Chinese martial artists have used the broadsword, straight sword, staff and spear for millennia. There is a well-established body of lore surrounding each weapon. Wharton said the spear was “supposedly the king of all weapons,” and called the staff the most versatile.

“The saying goes, ‘If a monk can defend against 10 attackers with one broadsword, he can defend against 40 attackers with a staff,'” he said.

As much as he would like to teach students the use of traditional weapons, he’s also willing to teach nothing but unarmed combat techniques. Wharton said that stances, strikes, blocks, kicks and forms were challenging and numerous enough to merit exclusive study.

There are many different styles of Kung Fu. Those developed in the north of China tend to emphasize more jumping, kicking and acrobatics, while those developed in the south emphasize hand strikes, feature low stances and are built on simpler, more direct techniques.

Some styles are named after animals. This is because the stances and techniques they prescribe resemble certain animals’ movements. One such style is the Shaolin Crane Style, which calls for one-legged stances and deft, balletic movements. Another is Monkey Style, practitioners of which stay close to the ground and avoid full extension of their limbs.

Wharton said that because he wants to give students as broad an introduction to Kung Fu as possible, he would teach a curriculum that brings together the best practices of many different styles.

“We cover a good general base,” Wharton said. “All the way from the stances to the basic drills.”

Wharton said he’d devote a good deal of time to what he called “Lama strikes.” Lama, he explained, is a martial arts style that features a number of methods for maximizing the power of attacks.

“The theory behind Lama is, whatever I hit — whether I’m punching or kicking or blocking — it’s going to break,” he said.

Wharton, who has practiced Kung Fu for the past 16 years, is devoted to his martial art of choice. But his devotion doesn’t blind him to its potentially daunting qualities.

He said that the term “Kung Fu” applies to far more than just systems of self-defense, extending to philosophy, sports, healing and art. For that reason, he believes it lacks the “pure focus” of a sport like boxing.

Wharton also said the rigor of Kung Fu might intimidate Westerners reared in a culture of instant gratification.

“For every 100 people that come in, one person’s going to stay,” he said.

But Wharton stressed that those with the will to practice would reap rewards.

“After a while, it starts to accumulate into an experience and a lifestyle that I wouldn’t trade for anything.”